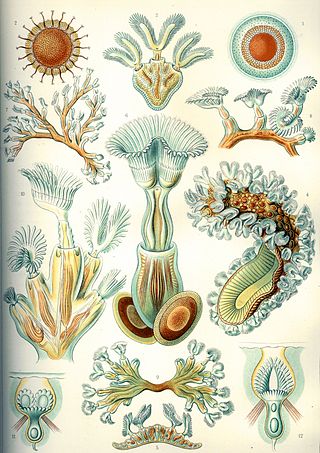

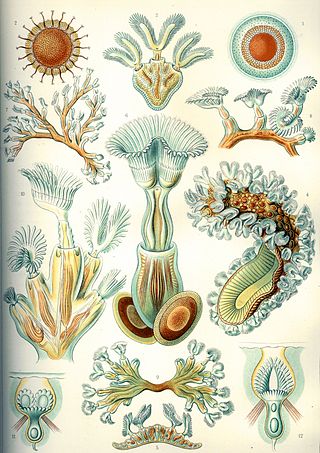

Bryozoa are a phylum of simple, aquatic invertebrate animals, nearly all living in sedentary colonies. Typically about 0.5 millimetres long, they have a special feeding structure called a lophophore, a "crown" of tentacles used for filter feeding. Most marine bryozoans live in tropical waters, but a few are found in oceanic trenches and polar waters. The bryozoans are classified as the marine bryozoans (Stenolaemata), freshwater bryozoans (Phylactolaemata), and mostly-marine bryozoans (Gymnolaemata), a few members of which prefer brackish water. 5,869 living species are known. Originally all of the crown group Bryozoa were colonial, but as an adaptation to a mesopsammal life or to deep‐sea habitats, secondarily solitary forms have since evolved. Solitary species has been described in four genera; Aethozooides, Aethozoon, Franzenella and Monobryozoon). The latter having a statocyst‐like organ with a supposed excretory function.

Cheilostomatida, also called Cheilostomata, is an order of Bryozoa in the class Gymnolaemata.

Membraniporidae is a bryozoan family in the order Cheilostomatida. Membranipora form encrusting or erect colonies; they are unilaminar or bilaminar and weakly to well-calcified. Zooids have vertical and basal calcified walls, but virtually no frontal calcified wall: most of the frontal surface is occupied by frontal membrane. An intertentacular organ is also present. The larvae are not brooded. The ancestrula is generally twinned. Kenozooids may be present in a few species; modified zooids analogous to avicularia are rare.

Membranipora membranacea is a very widely distributed species of marine bryozoan known from the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, usually in temperate zone environments. This bryozoan is a colonial organism characterized by a thin, mat-like encrustation, white to gray in color. It may be known colloquially as the coffin box, sea-mat or lacy crust bryozoan and is often abundantly found encrusting seaweeds, particularly kelps.

Malacostegina is a sub-order of marine, colonial bryozoans in the order Cheilostomatida. The structure of the individual zooids is generally simple, with an uncalcified, flexible frontal wall. This sub-order includes the earliest known cheilostome, in the genus Pyriporopsis (Electridae).

The avicularium in cheilostome bryozoans is a modified, non-feeding zooid. The operculum, which normally closes the orifice when the zooids tentacles are retracted, has been modified to become a mandible. Strong muscles operate it. The polypide is greatly reduced, and the individual receives nourishment from neighboring zooids. The shape of the avicularian zooid can be identical to the feeding autozooid, but is usually elongated in the direction of the mandible.

The Adeonellidae is a family within the bryozoan order Cheilostomatida. Colonies are often upright bilaminar branches or sheets. The zooids generally have one or more adventitious avicularia on their frontal wall. Instead of ovicells the adeonids often possess enlarged polymorphs which brood the larvae internally.

The Smittinidae is a family within the bryozoan order Cheilostomatida. Colonies are encrusting on shells and rocks or upright bilaminar branches or sheets. The zooids generally have at least one adventitious avicularia on their frontal wall near the orifice. The frontal wall is usually covered with small pores and numerous larger pores along the margin. The ovicell, which broods the larvae internally, is double-layered with numerous pores in the outer layer, and sits quite prominently on the frontal wall of the next zooid.

The Stomachetosellidae is a family within the bryozoan order Cheilostomatida. Colonies are encrusting on shells and rocks or upright bilaminar branches or sheets. The zooids generally have at least one adventitious avicularia on their frontal wall near the orifice. The frontal wall is usually covered with small pores and numerous larger pores along the margin. The ovicell, which broods the larvae internally, is double-layered with numerous pores in the outer layer, and sits quite prominently on the frontal wall of the next zooid.

The Bitectiporidae is a family within the bryozoan order Cheilostomatida. Colonies are encrusting on shells and rocks or upright bilaminar branches or sheets. The zooids generally have at least one adventitious avicularia on their frontal wall near the orifice. The frontal wall is usually covered with small pores and numerous larger pores along the margin. The ovicell, which broods the larvae internally, is double-layered with numerous pores in the outer layer, and sits quite prominently on the frontal wall of the next zooid.

Amathia vidovici is a species of colonial bryozoans with a tree-like structure. It is found in shallow waters over a wide geographical range, being found in both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and adjoining seas.

Amathia verticillata, commonly known as the spaghetti bryozoan, is a species of colonial bryozoans with a bush-like structure. It is found in shallow temperate and warm waters in the western Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea and has spread worldwide as a fouling organism. It is regarded as an invasive species in some countries.

Conopeum seurati is a species of colonial bryozoan in the order Cheilostomatida. It is native to the northeastern Atlantic Ocean, the North Sea and the Mediterranean Sea. This species has been introduced to New Zealand and Florida.

Electra pilosa is a species of colonial bryozoan in the order Cheilostomatida. It is native to the northeastern and northwestern Atlantic Ocean and is also present in Australia and New Zealand.

Watersipora subtorquata, commonly known as the red-rust bryozoan, is a species of colonial bryozoan in the family Watersiporidae. It is unclear from where it originated but it is now present in many warm-water coastal regions throughout the world, and has become invasive on the west coast of North America and in Australia and New Zealand.

Electra posidoniae is a species of bryozoan in the family Electridae. It is endemic to the Mediterranean Sea, and is commonly known as the Neptune-grass bryozoan because it is exclusively found growing on seagrasses, usually on Neptune grass, but occasionally on eelgrass.

Chorizopora brongniartii is a species of bryozoan in the family Chorizoporidae. It is an encrusting bryozoan, the colonies forming spreading patches. It has a widespread distribution in tropical and temperate seas.

Crisularia plumosa is a species of bryozoan belonging to the family Bugulidae, commonly known as the feather bryozoan. It is native to the Atlantic Ocean.

Walkeria uva is a species of colonial bryozoan in the order Ctenostomatida. It occurs on either side of the Atlantic Ocean, in the Baltic Sea, in the Mediterranean Sea and in the Indo-Pacific region.

Lichenalia is an extinct genus of cystoporate bryozoan belonging to the family Rhinoporidae. It is known from the Upper Ordovician to the Middle Silurian periods, which spanned from approximately 460 to 430 million years ago. The genus had a cosmopolitan distribution, with fossil specimens found in various regions of the world, including North America, Europe, and Asia.