Alchemy is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first attested in a number of pseudepigraphical texts written in Greco-Roman Egypt during the first few centuries AD.

Hermes Trismegistus is a legendary Hellenistic period figure that originated as a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth. He is the purported author of the Hermetica, a widely diverse series of ancient and medieval pseudepigraphica that lay the basis of various philosophical systems known as Hermeticism.

Hermeticism or Hermetism is a philosophical and religious system based on the purported teachings of Hermes Trismegistus. These teachings are contained in the various writings attributed to Hermes, which were produced over a period spanning many centuries and may be very different in content and scope.

The Hermetica are texts attributed to the legendary Hellenistic figure Hermes Trismegistus, a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth. These texts may vary widely in content and purpose, but are usually subdivided into two main categories, the "technical" and "religio-philosophical" Hermetica.

The Emerald Tablet, also known as the Smaragdine Tablet or the Tabula Smaragdina, is a compact and cryptic Hermetic text. It was highly regarded by Islamic and European alchemists as the foundation of their art. Though attributed to the legendary Hellenistic figure Hermes Trismegistus, the text of the Emerald Tablet first appears in a number of early medieval Arabic sources, the oldest of which dates to the late eighth or early ninth century. It was translated into Latin several times in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Numerous interpretations and commentaries followed.

In the magico-medical tradition of Europe and the Near East, the aetites or aetite (anglicized) is a stone used to promote childbirth. It is also called an eagle-stone, aquiline, or aquilaeus. The stone is said to prevent spontaneous abortion and premature delivery, while shortening labor and birth for a full-term birth.

Mary or Maria the Jewess, also known as Mary the Prophetess or Maria the Copt, was an early alchemist known from the works of Zosimos of Panopolis and other authors in the Greek alchemical tradition. On the basis of Zosimos's comments, she lived between the first and third centuries A.D. in Alexandria. French, Taylor and Lippmann list her as one of the first alchemical writers, dating her works at no later than the first century.

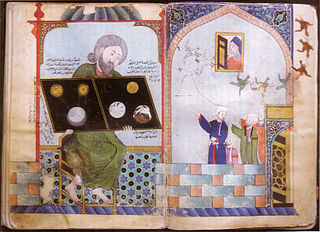

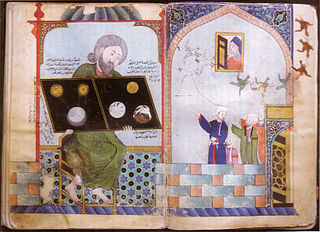

Picatrix is the Latin name used today for a 400-page book of magic and astrology originally written in Arabic under the title Ghāyat al-Ḥakīm, which most scholars assume was originally written in the middle of the 11th century, though an argument for composition in the first half of the 10th century has been made. The Arabic title translates as The Aim of the Sage or The Goal of The Wise. The Arabic work was translated into Spanish and then into Latin during the 13th century, at which time it got the Latin title Picatrix. The book's title Picatrix is also sometimes used to refer to the book's author.

Maria V. Mavroudi is a Greek-born American Byzantinist, historian, and philologist. She is a history professor at University of California, Berkeley.

Pseudo-Aristotle is a general cognomen for authors of philosophical or medical treatises who attributed their work to the Greek philosopher Aristotle, or whose work was later attributed to him by others. Such falsely attributed works are known as pseudepigrapha. The term Corpus Aristotelicum covers both the authentic and spurious works of Aristotle.

Agamede was a name attributed to two separate women in classical Greek mythology and legendary history.

In classical antiquity, including the Hellenistic world of ancient Greece and ancient Rome, historians and archaeologists view the public and private rituals associated with religion as part of everyday life. Examples of this phenomenon are found in the various state and cult temples, Jewish synagogues, and churches. These were important hubs for ancient peoples, representing a connection between the heavenly realms and the earthly planes. This context of magic has become an academic study, especially in the last twenty years.

Muḥammad ibn Umayl al-Tamīmī, known in Latin as Senior Zadith, was an early Muslim alchemist who lived from c. 900 to c. 960 AD.

The Medicina Plinii or Medical Pliny is an anonymous Latin compilation of medical remedies dating to the early 4th century AD. The excerptor, saying that he speaks from experience, offers the work as a compact resource for travelers in dealing with hucksters who sell worthless drugs at exorbitant prices or with know-nothings only interested in profit. The material is presented in three books in the conventional order a capite ad calcem, the first dealing with treatments pertaining to the head and throat, the second the torso and lower extremities, and the third systemic ailments, skin diseases, and poisons.

In the myth and folklore of the Near East and Europe, Abyzou is the name of a female demon. Abyzou was blamed for miscarriages and infant mortality and was said to be motivated by envy, as she herself was infertile. In the Coptic Egypt she is identified with Alabasandria, and in Byzantine culture with Gylou, but in various texts surviving from the syncretic magical practice of antiquity and the early medieval era she is said to have many or virtually innumerable names.

Demetrios Chloros was a 14th-century Byzantine physician, astrologer, priest and sorcerer who was tried for possessing magic books.

Pascalis Romanus was a 12th-century priest, medical expert, and dream theorist, noted especially for his Latin translations of Greek texts on theology, oneirocritics, and related subjects. An Italian working in Constantinople, he served as a Latin interpreter for Emperor Manuel I Komnenos.

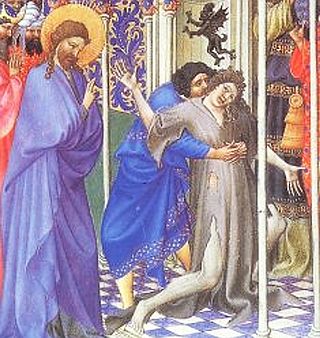

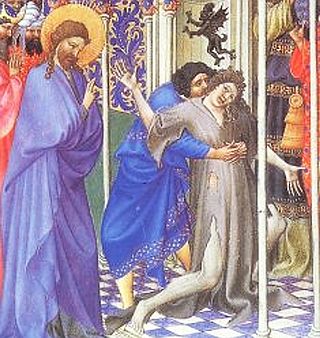

In English translations of the Bible, unclean spirit is a common rendering of Greek pneuma akatharton, which in its single occurrence in the Septuagint translates Hebrew ruaḥ tum'ah.

The Liber de compositione alchemiae, also known as the Testamentum Morieni, the Morienus, or by its Arabic title Masāʾil Khālid li-Maryānus al-rāhib, is a work on alchemy falsely attributed to the Umayyad prince Khalid ibn Yazid. It is generally considered to be the first Latin translation of an Arabic work on alchemy into Latin, completed on 11 February 1144 by the English Arabist Robert of Chester.

Leo Tuscus was an Italian writer and translator who served as a Latin–Greek interpreter in the imperial chancery of the Byzantine Empire under Emperor Manuel Komnenos.