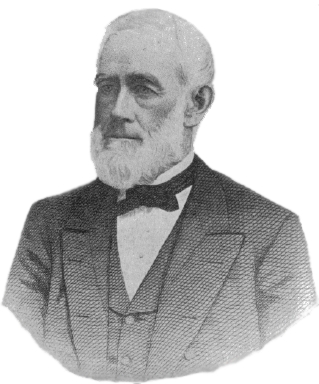

D. Augustus Straker (born 1842) was an American teacher, lawyer, and jurist. He won elections to the South Carolina legislature but was denied his seat on multiple occasions.

D. Augustus Straker (born 1842) was an American teacher, lawyer, and jurist. He won elections to the South Carolina legislature but was denied his seat on multiple occasions.

David Augustus Straker was born in Bridgetown, Barbados in 1842 to John and Margaret Straker. His father died when he was eleven months old and he was raised by his mother. He attended the Dame School until he was eleven, then had a private tutor for two years before entering the Central Public School of the Island led by Robert P. Elliott. He started to learn the tailor's trade, but did not enjoy it and withdrew, instead taking instruction in French and Latin under Rev. Joseph N. Durant and in education by R. R. Rawle at Codrington College. At the age of seventeen he was appointed principal of St. Mary's School and worked as a school teacher at St. Amis' School and St. Giles' School.

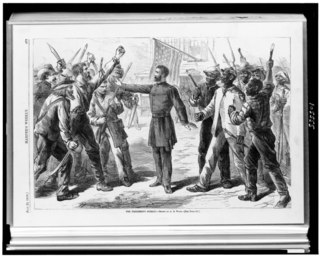

In 1866, Rev. Benjamin B. Smith, Episcopal Bishop of the Protestant Church of America, asked Rawle if there were any black people who would agree to emigrate to the United States to teach former slaves, and Straker volunteered. Straker began teaching in Louisville, Kentucky in schools set up by the Episcopal Church and the Freedmen's Bureau. He also began to prepare to become a minister, but did not pursue that career. In 1870, Straker was induced to enroll in Howard University Law School by John M. Langston, and he graduated in June 1871. While a student he worked as stenographer for Freedmen's Bureau head Oliver O. Howard. He also took a position as teacher at Howard in the Normal and Preparatory Department. He held a LL. B. degree from Howard University and a LL. D. from Selma University. [1]

In September 1871 he married Ann Carey, daughter of Thomas and Julia Carey, in Detroit, Michigan. [1]

In 1871 he was appointed clerk in the auditor's office of the United States Treasury Department in Washington, DC where he remained until 1875. He then took a position as Inspector of Customs at the port of Charleston, South Carolina. In 1876 he began practicing law in Orangeburg County, South Carolina, and was elected to the South Carolina House of Representatives as a Republican. In that election, incumbent Republican governor Daniel Henry Chamberlain and Democratic candidate Wade Hampton III both claimed victory and established separate governments. Eventually Chamberlain conceded and numerous Republican legislators including Straker were removed from the government. Straker was reelected in 1877 and 1878, but denied his seat both years.

In 1878 he formed a law partnership with Robert B. Elliott and T. McCants Stewart. Elliot was an agent of the Treasury Department and Straker was appointed special Inspector of Customs in Elliott's office. His political career would diminish, but in 1884 he was nominated Lieutenant-Governor at the Republican State Convention, but the ticket was abandoned. He was highly respected and befriended numerous important Republicans. He, George T. Downing, and James Wormley were the sole three black men who were with Charles Sumner at Sumner's death in 1874. [1]

In 1882, Straker became dean and law professor at Allen University in Columbia, South Carolina. He had become a well respected lawyer and had appeared in several important cases. A particular case was the defense of James Coleman, who was accused of Murder. R. G. Bonham represented the state, and Straker and Coleman won the case with an insanity plea. He also won two cases against the Bethel A.M.E. church, one regarding a property issue, and the other in support of the minister in dispute with a part of the congregation. In his law work, he worked with J. W. Morris, who would be elected president of Allen University in 1885. [1]

Straker also took part in numerous educational conventions and played an important role in the colored department of the 1884 World Cotton Centennial in New Orleans. He also was a noted speaker and wrote a number of articles for religious journals, particularly the A. M. E. Review . [1]

In 1885 he visited Detroit, Michigan where he was well received and gave a number of speeches. [1] He later moved to Detroit, Michigan, where he became the first black lawyer to appear before the Michigan Supreme Court. In 1890, in the case Ferguson v. Gies, Straker argued that the doctrine of "separate but equal" was unconstitutional according to Michigan law. [2] In the 1890s, Straker worked with Robert Pelham Jr. to create branches of the National Afro-American League in Michigan and the pair were active, in part through the league, in supporting blacks in legal trouble. [3]

Straker was one of the 56 prominent Detroit residents invited to contribute a letter to the Detroit Century Box, a time capsule organized by then-mayor William C. Maybury and sealed on December 31, 1900. [4] [5] It was opened on December 31, 2000.

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history, which lasted from the end of the American Civil War (1861–1865) until the Compromise of 1877. Its main goals were to rebuild the nation after the war, reintegrate the former Confederate states, and address the social, political, and economic impacts of slavery.

The Radical Republicans were a faction within the Republican Party originating from the party's founding in 1854—some six years before the Civil War—until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reconstruction. They called themselves "Radicals" because of their goal of immediate, complete, and permanent eradication of slavery in the United States. They were opposed during the war by the Moderate Republicans, and by the Democratic Party. Radicals led efforts after the war to establish civil rights for former slaves and fully implement emancipation. After unsuccessful measures in 1866 resulted in violence against former slaves in the rebel states, Radicals pushed the Fourteenth Amendment for statutory protections through Congress. They opposed allowing ex-Confederate officers to retake political power in the Southern U.S., and emphasized equality, civil rights and voting rights for the "freedmen", i.e., former slaves who had been freed during or after the Civil War by the Emancipation Proclamation and the Thirteenth Amendment.

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, usually referred to as simply the Freedmen's Bureau, was an agency of early Reconstruction, assisting freedmen in the South. It was established on March 3, 1865, and operated briefly as a U.S. government agency, from 1865 to 1872, after the American Civil War, to direct "provisions, clothing, and fuel...for the immediate and temporary shelter and supply of destitute and suffering refugees and freedmen and their wives and children".

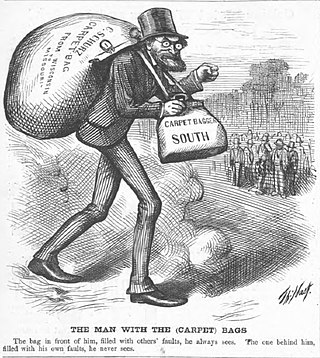

In the history of the United States, carpetbagger is a largely historical term used by Southerners to describe opportunistic Northerners who came to the Southern states after the American Civil War, who were perceived to be exploiting the local populace for their own financial, political, and/or social gain. The term broadly included both individuals who sought to promote Republican politics and individuals who saw business and political opportunities because of the chaotic state of the local economies following the war. In practice, the term carpetbagger was often applied to any Northerners who were present in the South during the Reconstruction Era (1865–1877). The term is closely associated with "scalawag", a similarly pejorative word used to describe native white Southerners who supported the Republican Party-led Reconstruction.

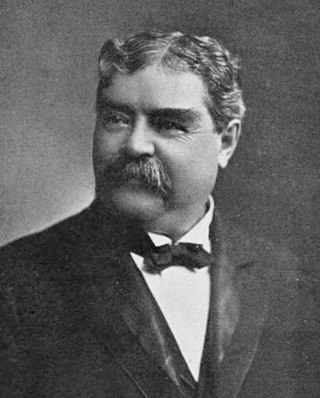

Daniel Henry Chamberlain was an American planter, lawyer, author and the 76th Governor of South Carolina from 1874 until 1876 or 1877. The federal government withdrew troops from the state and ended Reconstruction that year. Chamberlain was the last Republican governor of South Carolina until James B. Edwards was elected in 1974.

Jacob Merritt Howard was an American attorney and politician. He was most notable for his service as a U.S. Representative and U.S. Senator from the state of Michigan, and his political career spanned the American Civil War.

John Mercer Langston was an American abolitionist, attorney, educator, activist, diplomat, and politician. He was the founding dean of the law school at Howard University and helped create the department. He was the first president of what is now Virginia State University, a historically black college. He was elected a U.S. Representative from Virginia and wrote From the Virginia Plantation to the National Capitol; Or, the First and Only Negro Representative in Congress From the Old Dominion.

Robert Brown Elliott was a British-born American politician of British Afro-Caribbean ethnic background. He was a member of the United States House of Representatives from South Carolina, serving from 1871 to 1874.

William Alanson Howard served as a member of the United States House of Representatives from Michigan from March 4, 1855 to March 3, 1859 and from May 15, 1860 to March 3, 1861. Howard was the sixth Governor of the Dakota Territory from 1878 to 1880.

Archibald Henry Grimké was an African American lawyer, intellectual, journalist, diplomat and community leader in the 19th and early 20th centuries. He graduated from freedmen's schools, Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, and Harvard Law School and served as American Consul to the Dominican Republic from 1894 to 1898. He was an activist for rights for blacks, working in Boston and Washington, D.C. He was a national vice-president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), as well as president of its Washington, D.C. branch.

William Cotter Maybury was an American politician from the U.S. state of Michigan.

This is a selected bibliography of the main scholarly books and articles of Reconstruction, the period after the American Civil War, 1863–1877.

Benjamin Franklin Whittemore, also known as B. F. Whittemore, was a minister, politician, and publisher. After his theological studies, he was a minister and then during the Civil War, a chaplain for Massachusetts regiments. Stationed in South Carolina at the end of the war, he accepted a position of superintendent of education for the Freedmen's Bureau. He was a Republican U.S. Representative from South Carolina. He was censured in 1870 for selling appointments to the United States Naval Academy and other military academies. He spent his later years in Massachusetts, where he was a publisher.

The civil rights movement (1865–1896) aimed to eliminate racial discrimination against African Americans, improve their educational and employment opportunities, and establish their electoral power, just after the abolition of slavery in the United States. The period from 1865 to 1895 saw a tremendous change in the fortunes of the black community following the elimination of slavery in the South.

Thomas McCants Stewart was an African American clergyman, lawyer and civil rights leader.

Sumner Howard was an American jurist and politician who served as Chief Justice on the Arizona Territorial Supreme Court, Speaker of the Michigan House of Representatives, and Mayor of Prescott, Arizona Territory.

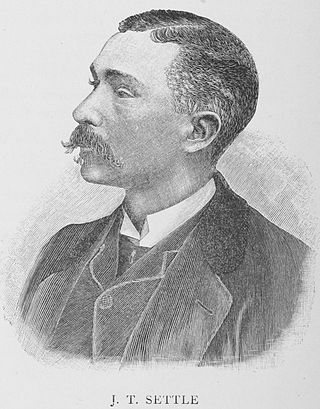

Josiah "Joe" Thomas Settle was a lawyer in Washington, D.C., Sardis, Mississippi, and Memphis, Tennessee. He was a part of Howard University's first graduating class in 1872. In 1875, he moved to Mississippi and was elected a member of the Mississippi House of Representatives in 1883. In 1885 he moved to Memphis where he was appointed Assistant Attorney-General in Shelby County. He held that position for two years before turning to private practice.

Robert A. Pelham Jr. was a journalist and civil servant in Detroit, Michigan and Washington, D.C. Along with his brother, Benjamin, and others, he was a founder and editor of the Detroit Plaindealer in 1883. He served in a number of public positions in Michigan, and later worked at the United States Census in Washington, D.C. In Washington, he continued to work as a journalist, and late in his life edited the weekly paper, Washington Tribune. He was also a member of a number of civil rights organizations, including the National Afro-American League, the American Negro Academy, and the Spingarn Medal Commission.