Alexander I, posthumously nicknamed The Fierce, was the King of Scotland from 1107 to his death. He succeeded his brother, King Edgar, and his successor was his brother David. He was married to Sybilla of Normandy, an illegitimate daughter of Henry I of England.

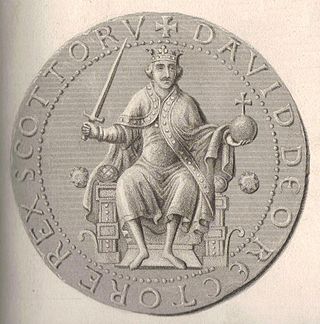

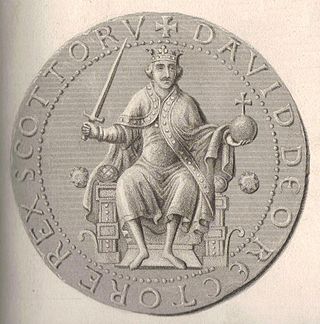

David I or Dauíd mac Maíl Choluim was a 12th-century ruler who was Prince of the Cumbrians from 1113 to 1124 and later King of Scotland from 1124 to 1153. The youngest son of Malcolm III and Margaret of Wessex, David spent most of his childhood in Scotland, but was exiled to England temporarily in 1093. Perhaps after 1100, he became a dependent at the court of King Henry I of England, by whom he was influenced.

Waltheof was a 12th-century English abbot and saint. He was the son of Simon I of St Liz, 1st Earl of Northampton and Maud, 2nd Countess of Huntingdon, thus stepson to David I of Scotland, and the grandson of Waltheof, Earl of Northampton.

Donnchadh was a Gall-Gaidhil prince and Scottish magnate in what is now south-western Scotland, whose career stretched from the last quarter of the 12th century until his death in 1250. His father, Gille-Brighde of Galloway, and his uncle, Uhtred of Galloway, were the two rival sons of Fergus, Prince or Lord of Galloway. As a result of Gille-Brighde's conflict with Uhtred and the Scottish monarch William the Lion, Donnchadh became a hostage of King Henry II of England. He probably remained in England for almost a decade before returning north on the death of his father. Although denied succession to all the lands of Galloway, he was granted lordship over Carrick in the north.

Christianity in Medieval Scotland includes all aspects of Christianity in the modern borders of Scotland in the Middle Ages. Christianity was probably introduced to what is now Lowland Scotland by Roman soldiers stationed in the north of the province of Britannia. After the collapse of Roman authority in the fifth century, Christianity is presumed to have survived among the British enclaves in the south of what is now Scotland, but retreated as the pagan Anglo-Saxons advanced. Scotland was largely converted by Irish missions associated with figures such as St Columba, from the fifth to the seventh centuries. These missions founded monastic institutions and collegiate churches that served large areas. Scholars have identified a distinctive form of Celtic Christianity, in which abbots were more significant than bishops, attitudes to clerical celibacy were more relaxed and there were significant differences in practice with Roman Christianity, particularly the form of tonsure and the method of calculating Easter, although most of these issues had been resolved by the mid-seventh century. After the reconversion of Scandinavian Scotland in the tenth century, Christianity under papal authority was the dominant religion of the kingdom.

The Bishop of St. Andrews was the ecclesiastical head of the Diocese of St Andrews in the Catholic Church and then, from 14 August 1472, as Archbishop of St Andrews, the Archdiocese of St Andrews.

Robert of Scone was a 12th-century bishop of Cell Rígmonaid. Robert's exact origins are unclear. He was an Augustinian canon at the Priory of St. Oswalds, at Nostell. His French name indicates a Norman rather than an Anglo-Saxon origin, but as he was likely born in the later 11th century, this may be due merely to the acculturation of his parents.

Jocelin was a twelfth-century Cistercian monk and cleric who became the fourth Abbot of Melrose before becoming Bishop of Glasgow, Scotland. He was probably born in the 1130s, and in his teenage years became a monk of Melrose Abbey. He rose in the service of Abbot Waltheof, and by the time of the short abbacy of Waltheof's successor Abbot William, Jocelin had become prior. Then in 1170 Jocelin himself became abbot, a position he held for four years. Jocelin was responsible for promoting the cult of the emerging Saint Waltheof, and in this had the support of Enguerrand, Bishop of Glasgow.

Robert Blackadder was a medieval Scottish cleric, diplomat and politician, who was abbot of Melrose, bishop-elect of Aberdeen and bishop of Glasgow; when the last was elevated to archiepiscopal status in 1492, he became the first ever archbishop of Glasgow. Archbishop Robert Blackadder died on 28 July 1508, while en route to Jerusalem on pilgrimage.

John was an early 12th-century Tironensian cleric. He was the chaplain and close confidant of King David I of Scotland, before becoming Bishop of Glasgow and founder of Glasgow Cathedral. He was one of the most significant religious reformers in the history of Scotland. His later nickname, "Achaius", a latinisation of Eochaid would indicate that he was Gaelic, but the name is probably not authentic. He was in fact a Tironensian monk, of probable French origin.

The Prior, then Abbot and then Commendator of Dunfermline was the head of the Benedictine monastic community of Dunfermline Abbey, Fife, Scotland. The abbey itself was founded in 1128 by King David I of Scotland, but was of earlier origin. King Máel Coluim mac Donnchada had founded a church there with the help of Benedictines from Canterbury. Monks had been sent there in the reign of Étgar mac Maíl Choluim and Anselm had sent a letter requesting that Étgar's brother and successor King Alaxandair mac Maíl Coluim protect these monks. By 1120, when Alaxandair sent a delegation to Canterbury to secure Eadmer for the bishopric of St Andrews, there is a Prior of the Dunfermline monks by the name of Peter leading the delegation. Control of the abbey was secularized in the 16th century and after the accession of James Stewart in 1500, the abbey was held by commendators. In the second half of the 16th century, the abbey's lands were being carved up into lordships and it was finally annexed to the crown in July, 1593.

Clement was a 13th-century Dominican friar who was the first member of the Dominican Order in Britain and Ireland to become a bishop. In 1233, he was selected to lead the ailing diocese of Dunblane in Scotland, and faced a struggle to bring the bishopric of Dunblane to financial viability. This involved many negotiations with the powerful religious institutions and secular authorities which had acquired control of the revenue that would normally have been the entitlement of Clement's bishopric. The negotiations proved difficult, forcing Clement to visit the papal court in Rome. While not achieving all of his aims, Clement succeeded in saving the bishopric from relocation to Inchaffray Abbey. He also regained enough revenue to begin work on the new Dunblane Cathedral.

Before David I became the King of Scotland in 1124, he was the prince of the Cumbrians and earl of a great territory in the middle of England acquired by marriage. This period marks the beginning of his life as a great territorial lord. Circa 1113, the year in which King Henry I of England arranged his marriage to an English heiress and the year in which for the first time David can be found in possession of "Scottish" territory, marks the beginning of his rise to Scottish leadership.

The relationship between the Kingdom of England and King David I, who was King of Scotland between 1124 and 1153, was partly shaped by David's relationship with the particular King of England, and partly by David's own ambition. David had a good relationship with and was an ally of Henry I of England, the King who was largely responsible for David's early career. After Henry's death, David upheld his support for his niece, the former Empress-consort, Matilda, and expanded his power in northern England in the process, despite his defeat at the Battle of the Standard in 1138.

The Davidian Revolution is a name given by many scholars to the changes which took place in the Kingdom of Scotland during the reign of David I (1124–1153). These included his foundation of burghs, implementation of the ideals of Gregorian Reform, foundation of monasteries, Normanisation of the Scottish government, and the introduction of feudalism through immigrant Norman and Anglo-Norman knights.

John of Whithorn was the medieval Bishop of Galloway. His first appearance as bishop-elect is at the coronation of Richard, Cœur de Lion as King of the English at Westminster Abbey on 3 September 1189. He was consecrated at Pipewell Abbey, Northamptonshire, on Sunday 17 September 1189.

Henry was a 13th-century Augustinian abbot and bishop, most notable for holding the positions of Abbot of Holyrood and Bishop of Galloway.

Gilbert was a 13th-century Cistercian monk, abbot and bishop. His first appearance in the sources occurs under the year 1233, for which year the Chronicle of Melrose reported that "Sir Gilbert, the abbot of Glenluce, resigned his office, in the chapter of Melrose; and there he made his profession". It is not clear why Gilbert really did resign the position of Abbot of Glenluce, head of Glenluce Abbey in Galloway, in order to become a mere brother at Melrose Abbey; nor is it clear for how long Gilbert had been abbot, though his latest known predecessor is attested last on 27 May 1222. After going to there, Gilbert became the Master of the Novices at Melrose.

Odo Ydonc was a 13th-century Premonstratensian prelate. The first recorded appearance of Odo was when he witnessed a charter by Donnchadh, Earl of Carrick, on 21 July 1225. In this document he is already Abbot of Dercongal, incidentally the first Abbot of Dercongal to appear on record.

Reinald Macer [also called Reginald] was a medieval Cistercian monk and bishop, active in the Kingdom of Scotland during the reign of William the Lion. Originally a monk of Melrose Abbey, he rose to become Bishop of Ross in 1195, and held this position until his death in 1213. He is given the nickname Macer in Roger of Howden's Chronica, a French word that meant "skinny".