Hunting is the human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, and killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to obtain the animal's body for meat and useful animal products, for recreation/taxidermy, although it may also be done for resourceful reasons such as removing predators dangerous to humans or domestic animals, to eliminate pests and nuisance animals that damage crops/livestock/poultry or spread diseases, for trade/tourism, or for ecological conservation against overpopulation and invasive species.

Tapestry is a form of textile art, traditionally woven by hand on a loom. Normally it is used to create images rather than patterns. Tapestry is relatively fragile, and difficult to make, so most historical pieces are intended to hang vertically on a wall, or sometimes horizontally over a piece of furniture such as a table or bed. Some periods made smaller pieces, often long and narrow and used as borders for other textiles. Most weavers use a natural warp thread, such as wool, linen, or cotton. The weft threads are usually wool or cotton but may include silk, gold, silver, or other alternatives.

Falconry is the hunting of wild animals in their natural state and habitat by means of a trained bird of prey. Small animals are hunted; squirrels and rabbits often fall prey to these birds. Two traditional terms are used to describe a person involved in falconry: a "falconer" flies a falcon; an "austringer" keeps Goshawks and uses accipiters for hunting. In modern falconry, the red-tailed hawk, Harris's hawk, and the peregrine falcon are some of the more commonly used birds of prey. The practice of hunting with a conditioned falconry bird is also called "hawking" or "gamehawking", although the words hawking and hawker have become used so much to refer to petty traveling traders, that the terms "falconer" and "falconry" now apply to most use of trained birds of prey to catch game. However, many contemporary practitioners still use these words in their original meaning.

Game or quarry is any wild animal hunted for animal products, for recreation ("sporting"), or for trophies. The species of animals hunted as game varies in different parts of the world and by different local jurisdictions, though most are terrestrial mammals and birds. Fish caught non-commercially are also referred to as game fish.

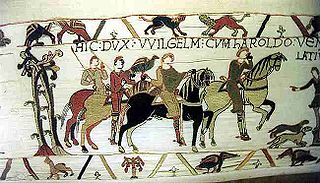

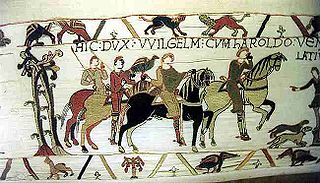

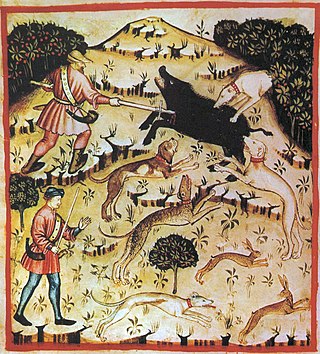

Coursing by humans is the pursuit of game or other animals by dogs—chiefly greyhounds and other sighthounds—catching their prey by speed, running by sight, but not by scent. Coursing was a common hunting technique, practised by the nobility, the landed and wealthy, as well as by commoners with sighthounds and lurchers. In its oldest recorded form in the Western world, as described by Arrian—it was a sport practised by all levels of society, and it remained the case until Carolingian period forest law appropriated hunting grounds, or commons, for the king, the nobility, and other landowners. It then became a formalised competition, specifically on hare in Britain, practised under rules, the Laws of the Leash'.

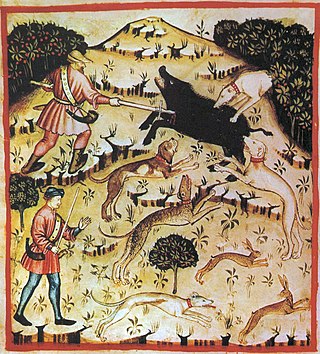

Royal hunting, also royal art of hunting, was a hunting practice of the aristocracy throughout the known world in the Middle Ages, from Europe to Far East. While humans hunted wild animals since time immemorial, and all classes engaged in hunting as an important source of food and at times the principal source of nutrition, the necessity of hunting was transformed into a stylized pastime of the aristocracy. In Europe in the High Middle Ages the practice was widespread.

The Grand Bleu de Gascogne is a breed of hounds of the scenthound type, originating in France and used for hunting in packs. Today's breed is the descendant of a very old type of large hunting dog, and is an important breed in the ancestry of many other hounds.

Hunting in Russia has an old tradition in terms of indigenous people, while the original features of state and princely economy were farming and cattle-breeding. There was hunting for food as well as sport. The word "hunting" first appeared in the common Russian language at the end of the 15th century. Before that the word "catchings" existed to designate the hunting business in general. The hunting grounds were called in turn lovishcha ("ловища"). In the 15th-16th centuries, foreign ambassadors were frequently invited to hunts; they also received some of the prey afterwards.

Boar hunting is the practice of hunting wild boar, feral pigs, warthogs, and peccaries. Boar hunting was historically a dangerous exercise due to the tusked animal's ambush tactics as well as its thick hide and dense bones rendering them difficult to kill with premodern weapons.

Bears have been hunted since prehistoric times for their meat and fur. In addition to being a source of food, in modern times they have been favored by big game hunters due to their size and ferocity. Bear hunting has a vast history throughout Europe and North America, and hunting practices have varied based on location and type of bear.

Romania has a long history of hunting and remains a remarkable hunting destination, drawing many hunters because of its large numbers of brown bears, wolves, wild boars, red deer, and chamois. The concentration of brown bears in the Carpathian Mountains of central Romania is largest in the world and contains half of all Europe's population, except Russia.

The Sabueso Español or Spanish Hound is a scenthound breed with its origin in the far north of Iberian Peninsula. This breed has been used in this mountainous region since hundreds of years ago for all kind of game: wild boar, hare, brown bear, wolf, red deer, fox, roe deer and chamois. It is an exclusive working breed, employed in hunting with firearms.

Game preservation is maintaining a stock of game to be hunted legally. It includes:

Rache, also spelled racch, rach, and ratch, from Old English ræcc, linked to Old Norse rakkí, is an obsolete name for a type of hunting dog used in Great Britain in the Middle Ages. It was a scenthound used in a pack to run down and kill game, or bring it to bay. The word appears before the Norman Conquest. It was sometimes confused with 'brache', which is a French derived word for a female scenthound.

A hart is a male red deer, synonymous with stag and used in contrast to the female hind; its use may now be considered mostly poetic or archaic. The word comes from Middle English hert, from Old English heorot; compare Frisian hart, Dutch hert, German Hirsch, and Swedish, Norwegian, and Danish hjort, all meaning "deer". Heorot is given as the name of Hrothgar's mead hall in the Old English epic Beowulf.

A limer, or lymer, was a kind of dog, a scenthound, used on a leash in medieval times to find large game before it was hunted down by the pack. It was sometimes known as a lyam hound/dog or lime-hound, from the Middle English word lyam, meaning 'leash'. The French cognate limier has sometimes been used for the dogs in English as well. The type is not to be confused with the bandog, which was also a dog controlled by a leash, typically a chain, but was a watchdog or guard dog.

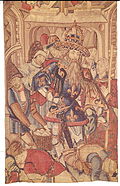

The Hunts of Maximilian or Les Chasses de Maximilien, also Les Belles chasses de Guise are a set of twelve tapestries, one per month, depicting hunting scenes in the Sonian Forest, south of Brussels, by the court of Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor. They were produced in a Brussels workshop, and several tapestries are given identifiable locations that were then around the outskirts of the city, but are now mostly engulfed by it. The set is now in the Louvre.

A montería is an ancient type of driven hunt endemic to Spain. It involves the tracking, chase and killing of big-game, typically red deer, wild boar, fallow deer and mouflon. A number of "rehalas" along with their respective "rehaleros" will stir up an area of forest with the aim of forcing the game to move around and into the shooting pegs, where hunters will be able to fire.

The Staghound, sometimes referred to as the English Staghound, is an extinct breed of scent hound from England. A pack hound, the breed was used to hunt red deer and became extinct in the 19th century when the last pack was sold.

In Great Britain and Ireland a sporting lodge – also known as a hunting lodge, hunting box, fishing hut, shooting box, or shooting lodge – is a building designed to provide lodging for those practising the sports of hunting, shooting, fishing, stalking, falconry, coursing and other similar rural sporting pursuits.