Distance education, also known as distance learning, is the education of students who may not always be physically present at school, or where the learner and the teacher are separated in both time and distance. Traditionally, this usually involved correspondence courses wherein the student corresponded with the school via mail. Distance education is a technology-mediated modality and has evolved with the evolution of technologies such as video conferencing, TV, and the Internet. Today, it usually involves online education and the learning is usually mediated by some form of technology. A distance learning program can either be completely a remote learning, or a combination of both online learning and traditional offline classroom instruction. Other modalities include distance learning with complementary virtual environment or teaching in virtual environment (e-learning).

WLS is a commercial AM radio station in Chicago, Illinois. Owned by Cumulus Media, through licensee Radio License Holdings LLC, the station airs a talk radio format. WLS has its radio studios in the NBC Tower on North Columbus Drive in the city's Streeterville neighborhood. Its non-directional broadcast tower is located on the southwestern edge of Tinley Park, Illinois in Will County.

WGN is a commercial AM radio station in Chicago, Illinois, featuring a talk radio format. WGN's studios are in the Chicago Loop, while the transmitter is in Elk Grove Village. WGN also features broadcasts of Chicago Blackhawks hockey and Northwestern University football and basketball.

WBEZ – branded WBEZ 91.5 – is a non-commercial educational radio station licensed to Chicago, Illinois, and primarily serving the Chicago metropolitan area. It is owned by Chicago Public Media and is financed by listener contributions, corporate underwriting and some government funding. WBEZ is affiliated with both National Public Radio (NPR) and the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). It also broadcasts content from American Public Media and the BBC World Service. It produces several nationally syndicated shows for public radio stations, including This American Life and has a co-production credit for Wait Wait... Don't Tell Me!, which is produced by NPR.

Chicago Public Schools (CPS), officially classified as City of Chicago School District #299 for funding and districting reasons, in Chicago, Illinois, is the fourth-largest school district in the United States, after New York, Los Angeles, and Miami-Dade County. For the 2020–21 school year, CPS reported overseeing 638 schools, including 476 elementary schools and 162 high schools; of which 513 were district-run, 115 were charter schools, 9 were contract schools and 1 was a SAFE school. The district serves 340,658 students. Chicago Public School students attend a particular school based on their area of residence, except for charter, magnet, and selective enrollment schools.

WIND is a commercial AM radio station licensed to Chicago, Illinois, and broadcasting a conservative talk radio format. It is owned by the Salem Media Group with studios on NW Point Boulevard in Elk Grove Village.

WYLL is a commercial radio station in Chicago, Illinois. It originated as WJJD and broadcast some pioneering shows. It is owned by Salem Media Group and airs a Christian talk and teaching radio format. The studios and offices are located in Elk Grove Village. Its daytime transmitter and two-tower array are located off Ballard Road near Interstate 294 in Des Plaines. The nighttime transmitter and six-tower array are off Deer Drive near Interstate 355 in Lockport. WYLL is powered with 50,000 watts, the maximum for commercial AM stations in the U.S. But it must use a directional antenna at all times to protect clear-channel station KSL in Salt Lake City, the dominant Class A station and several Class B stations on 1160 AM.

Universitas Terbuka is Indonesia state university that employs an Open and Distance Learning (ODL) system to widen access to higher education to all Indonesian citizens, including those who live in remote islands throughout the country, and in various parts of the world. It has a total student body of 1,045,665. According to a distance education institution in the UK, which published "The Top Ten Mega Universities", UT-3 ranks closely with universities from China and Turkey.

Calumet College of St. Joseph is a private Roman Catholic college in Hammond, Indiana. It was founded in 1951 as an extension of Saint Joseph's College and is associated with the Missionaries of the Precious Blood. In fall 2022, it enrolled 658 undergraduates and 95 graduate students.

Wendell Phillips Academy High School is a public 4-year high school located in the Bronzeville neighborhood on the south side of Chicago, Illinois, United States. Opened in September 1904, Phillips is part of the Chicago Public Schools district and is managed by the Academy for Urban School Leadership. Phillips is named for the American abolitionist Wendell Phillips. Phillips is known as the first predominantly African-American high school in the City of Chicago. Phillips' building was designated a Chicago Landmark on May 7, 2003.

Chicago Public Media (CPM) is a not-for-profit radio and print media company. CPM operates as the primary National Public Radio member organization for Chicago. It owns three non-commercial educational FM broadcast stations and one FM translator. In addition to local news and information productions, it produces the programs Wait Wait... Don't Tell Me! for NPR stations, and This American Life which is distributed by PRX to other radio stations. On January 30, 2022, Chicago Public Media acquired the Chicago Sun-Times daily newspaper.

The Alternative Learning System (ALS) is a parallel learning system in the Philippines that provides a practical option to the existing formal instruction. When one does not have or cannot access formal education in schools, ALS is an alternate or substitute. System only requires learners to attend learning sessions based on the agreed schedule between the learners and the learning facilitators.

Alberta Distance Learning Centre (ADLC) was an educational organization that provided distance and distributed education services to primary and secondary students. It was based out of Barrhead, Alberta, Canada. ADLC ceased operation following the 2020–21 school year after it was defunded by the provincial government.

Edward Jenner School, also known as Edward Jenner Elementary Academy of the Arts, was a public PK-8 school located in the Cabrini-Green area of the Near North Side, Chicago, Illinois, United States. Named after Edward Jenner, The school was opened and operated by the Chicago Public Schools (CPS). Jenner merged with Ogden International School in September 2018. The campus is now Ogden International–Jenner which serves grades Pre–K, 5th through 8th.

The COVID-19 pandemic affected educational systems across the world. The number of cases of COVID-19 started to rise in March 2020 and many educational institutions and universities underwent closure. Most countries decided to temporarily close educational institutions in order to reduce the spread of COVID-19. UNESCO estimates that at the height of the closures in April 2020, national educational shutdowns affected nearly 1.6 billion students in 200 countries: 94% of the student population and one-fifth of the global population. Closures are estimated to have lasted for an average of 41 weeks. They have had significant negative effects on student learning, which are predicted to have substantial long-term implications for both education and earnings. During the pandemic, education budgets and official aid program budgets for education have decreased.

John Dill Robertson was an American medical professional and politician. He served as Chicago's city health commissioner, president of the Chicago Board of Education, and president of the Chicago West Parks Board. In 1927, Robertson ran a third-party campaign for Chicago mayor. As a politician, Thompson was affiliated with the Republican Party. He was an ally of Republican boss Frederick Lundin, and prior to his 1927 mayoral campaign against him, had also long been an ally of William Hale Thompson.

Herman Niels Bundesen was a German-American medical professional, politician, and author. He served two tenures as the chief health official of the city of Chicago, holding this role for more than 34 years in total. He also was elected Cook County coroner. In 1936, he ran unsuccessfully for the Democratic Party nomination for governor of Illinois.

In 2020, school systems in the United States began to close down in March because of the spread of COVID-19. This was a historic event in the history of the United States schooling system because it forced schools to shut-down. At the very peak of school closures, COVID-19 affected 55.1 million students in 124,000 public and private U.S. schools. The effects of widespread school shut-downs were felt nationwide, and aggravated several social inequalities in gender, technology, educational achievement, and mental health.

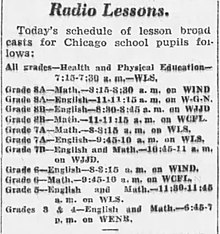

William Harding Johnson was an American educator who served as superintendent of Chicago Public Schools. His decade-long tenure as superintendent was controversial, and ended with him being pressured to resign after the National Education Association released a report which detailed corrupt and unethical actions by Johnson and the Chicago Board of Education, which resulted in the North Central Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools threatening to revoke its accreditation of Chicago Public Schools' high schools. Despite his controversy, he had a number of successes, such as being credited with decreased school truancy. He also introduced innovations to the school system, such as introducing an innovative remote education approach that utilized radio broadcasts amid school closures during a 1937 polio outbreak.

History of education in Chicago covers the schools of the city since the 1830s. It includes all levels as well as public, private and parochial schools. For the recent history since the 1970s see Chicago Public Schools