Reaganomics, or Reaganism, were the neoliberal economic policies promoted by U.S. President Ronald Reagan during the 1980s. These policies are characterized as supply-side economics, trickle-down economics, or "voodoo economics" by opponents, while Reagan and his advocates preferred to call it free-market economics.

The Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act is an act of legislation by the United States government.

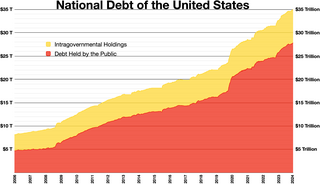

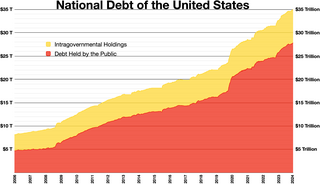

The national debt of the United States is the total national debt owed by the federal government of the United States to Treasury security holders. The national debt at any point in time is the face value of the then-outstanding Treasury securities that have been issued by the Treasury and other federal agencies. The terms "national deficit" and "national surplus" usually refer to the federal government budget balance from year to year, not the cumulative amount of debt. In a deficit year the national debt increases as the government needs to borrow funds to finance the deficit, while in a surplus year the debt decreases as more money is received than spent, enabling the government to reduce the debt by buying back some Treasury securities. In general, government debt increases as a result of government spending and decreases from tax or other receipts, both of which fluctuate during the course of a fiscal year. There are two components of gross national debt:

The economic policies of Bill Clinton administration, referred to by some as Clintonomics, encapsulates the economic policies of president of the United States Bill Clinton that were implemented during his presidency, which lasted from January 1993 to January 2001.

Fiscal policy is any changes the government makes to the national budget to influence a nation's economy. "An essential purpose of this Financial Report is to help American citizens understand the current fiscal policy and the importance and magnitude of policy reforms essential to make it sustainable. A sustainable fiscal policy is explained as the debt held by the public to Gross Domestic Product which is either stable or declining over the long term". The approach to economic policy in the United States was rather laissez-faire until the Great Depression. The government tried to stay away from economic matters as much as possible and hoped that a balanced budget would be maintained. Prior to the Great Depression, the economy did have economic downturns and some were quite severe. However, the economy tended to self-correct so the laissez faire approach to the economy tended to work.

The United States budget comprises the spending and revenues of the U.S. federal government. The budget is the financial representation of the priorities of the government, reflecting historical debates and competing economic philosophies. The government primarily spends on healthcare, retirement, and defense programs. The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office provides extensive analysis of the budget and its economic effects. CBO estimated in February 2023 that Federal debt held by the public is projected to rise from 98 percent of GDP in 2023 to 118 percent in 2033—an average increase of 2 percentage points per year. Over that period, the growth of interest costs and mandatory spending outpaces the growth of revenues and the economy, driving up debt. Those factors persist beyond 2033, pushing federal debt higher still, to 195 percent of GDP in 2053.

The economic policy and legacy of the George W. Bush administration was characterized by significant income tax cuts in 2001 and 2003, the implementation of Medicare Part D in 2003, increased military spending for two wars, a housing bubble that contributed to the subprime mortgage crisis of 2007–2008, and the Great Recession that followed. Economic performance during the period was adversely affected by two recessions, in 2001 and 2007–2009.

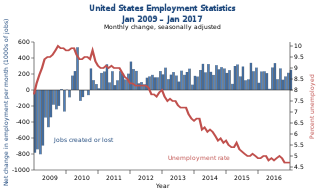

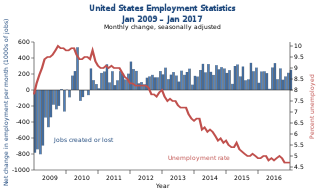

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA), nicknamed the Recovery Act, was a stimulus package enacted by the 111th U.S. Congress and signed into law by President Barack Obama in February 2009. Developed in response to the Great Recession, the primary objective of this federal statute was to save existing jobs and create new ones as soon as possible. Other objectives were to provide temporary relief programs for those most affected by the recession and invest in infrastructure, education, health, and renewable energy.

In economics, stimulus refers to attempts to use monetary policy or fiscal policy to stimulate the economy. Stimulus can also refer to monetary policies such as lowering interest rates and quantitative easing.

Beginning in 2008 many nations of the world enacted fiscal stimulus plans in response to the Great Recession. These nations used different combinations of government spending and tax cuts to boost their sagging economies. Most of these plans were based on the Keynesian theory that deficit spending by governments can replace some of the demand lost during a recession and prevent the waste of economic resources idled by a lack of demand. The International Monetary Fund recommended that countries implement fiscal stimulus measures equal to 2% of their GDP to help offset the global contraction. In subsequent years, fiscal consolidation measures were implemented by some countries in an effort to reduce debt and deficit levels while at the same time stimulating economic recovery.

The economic policy of the Barack Obama administration, or in its colloquial portmanteau form "Obamanomics", was characterized by moderate tax increases on higher income Americans designed to fund health care reform, reduce the federal budget deficit, and decrease income inequality. President Obama's first term (2009–2013) included measures designed to address the Great Recession and subprime mortgage crisis, which began in 2007. These included a major stimulus package, banking regulation, and comprehensive healthcare reform. As the economy improved and job creation continued during his second term (2013–2017), the Bush tax cuts were allowed to expire for the highest income taxpayers and a spending sequester (cap) was implemented, to further reduce the deficit back to typical historical levels. The number of persons without health insurance was reduced by 20 million, reaching a record low level as a percent of the population. By the end of his second term, the number of persons with jobs, real median household income, stock market, and real household net worth were all at record levels, while the unemployment rate was well below historical average.

Unemployment in the United States discusses the causes and measures of U.S. unemployment and strategies for reducing it. Job creation and unemployment are affected by factors such as economic conditions, global competition, education, automation, and demographics. These factors can affect the number of workers, the duration of unemployment, and wage levels.

Political debates about the United States federal budget discusses some of the more significant U.S. budgetary debates of the 21st century. These include the causes of debt increases, the impact of tax cuts, specific events such as the United States fiscal cliff, the effectiveness of stimulus, and the impact of the Great Recession, among others. The article explains how to analyze the U.S. budget as well as the competing economic schools of thought that support the budgetary positions of the major parties.

Deficit reduction in the United States refers to taxation, spending, and economic policy debates and proposals designed to reduce the federal government budget deficit. Government agencies including the Government Accountability Office (GAO), Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), and the U.S. Treasury Department have reported that the federal government is facing a series of important long-run financing challenges, mainly driven by an aging population, rising healthcare costs per person, and rising interest payments on the national debt.

The United States fiscal cliff refers to the combined effect of several previously-enacted laws that came into effect simultaneously in January 2013, increasing taxes and decreasing spending.

The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA) was enacted and passed by the United States Congress on January 1, 2013, and was signed into law by US President Barack Obama the next day. ATRA gave permanence to the lower rates of much of the "Bush tax cuts".

The economic policy of the Donald Trump administration was characterized by the individual and corporate tax cuts, attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act ("Obamacare"), trade protectionism, immigration restriction, deregulation focused on the energy and financial sectors, and responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, also known as the CARES Act, is a $2.2 trillion economic stimulus bill passed by the 116th U.S. Congress and signed into law by President Donald Trump on March 27, 2020, in response to the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. The spending primarily includes $300 billion in one-time cash payments to individual people who submit a tax return in America, $260 billion in increased unemployment benefits, the creation of the Paycheck Protection Program that provides forgivable loans to small businesses with an initial $350 billion in funding, $500 billion in loans for corporations, and $339.8 billion to state and local governments.

The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, also called the COVID-19 Stimulus Package or American Rescue Plan, is a US$1.9 trillion economic stimulus bill passed by the 117th United States Congress and signed into law by President Joe Biden on March 11, 2021, to speed up the country's recovery from the economic and health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing recession. First proposed on January 14, 2021, the package builds upon many of the measures in the CARES Act from March 2020 and in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, from December.

The economic policy of the Joe Biden administration, dubbed Bidenomics, is characterized by relief measures and vaccination efforts to address the COVID-19 pandemic, investments in infrastructure, and strengthening the social safety net, funded by tax increases on higher-income individuals and corporations. Other goals include increasing the national minimum wage and expanding worker training, narrowing income inequality, expanding access to affordable healthcare, and forgiveness of student loan debt. The March 2021 enactment of the American Rescue Plan to provide relief from the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was the first major element of the policy. Biden's Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act was signed into law in November 2021 and contains about $550 billion in additional investment. His Inflation Reduction Act was enacted in August 2022.