The Gaza Strip, or simply Gaza, is a polity and the smaller of the two Palestinian territories. On the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea, Gaza is bordered by Egypt on the southwest and Israel on the east and north.

The Palestinian Authority, officially known as the Palestinian National Authority or the State of Palestine, is the Fatah-controlled government body that exercises partial civil control over West Bank areas "A" and "B" as a consequence of the 1993–1995 Oslo Accords. The Palestinian Authority controlled the Gaza Strip prior to the Palestinian elections of 2006 and the subsequent Gaza conflict between the Fatah and Hamas parties, when it lost control to Hamas; the PA continues to claim the Gaza Strip, although Hamas exercises de facto control. Since January 2013, the Palestinian Authority has used the name "State of Palestine" on official documents, although the United Nations continues to recognize the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) as the "representative of the Palestinian people".

The Israeli–Palestinian conflict is an ongoing military and political conflict about land and self-determination within the territory of the former Mandatory Palestine. Key aspects of the conflict include the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, the status of Jerusalem, Israeli settlements, borders, security, water rights, the permit regime, Palestinian freedom of movement, and the Palestinian right of return.

Gaza, also called Gaza City, is a Palestinian city in the Gaza Strip. Prior to the 2023 Israel–Hamas war, it was the most populous city in the State of Palestine, with 590,481 inhabitants in 2017.

The Gaza–Israel barrier is a border barrier located on the Israeli side of the Gaza–Israel border. Before the 2023-24 Israel-Hamas war, the Erez Crossing, in the north of the Gaza Strip, used to be the only crossing point for people and goods coming from Israel into the Gaza Strip, with a second crossing point, the Kerem Shalom border crossing, used exclusively for goods coming from Egypt, as Israel didn't allow goods to go directly from Egypt into Gaza through the Egypt–Gaza border, except for the Salah Al Din Gate, opened in 2018.

The Gaza Strip smuggling tunnels are smuggling tunnels that had been dug under the Philadelphi Route along the Egypt–Gaza border. They were dug to subvert the blockade of the Gaza Strip to smuggle in fuel, food, weapons and other goods into the Gaza Strip. After the Egypt–Israel peace treaty of 1979, the town of Rafah, in the southern Gaza Strip, was split by this buffer zone. One part is located in the southern part of Gaza, and the smaller part of the town is in Egypt. After Israel withdrew from Gaza in 2005, the Philadelphi Corridor was placed under the control of the Palestine Authority until 2007, when Hamas seized power in 2007, and Egypt and Israel closed borders with the Gaza Strip.

The economy of the State of Palestine refers to the economic activity of the State of Palestine. Palestine receives substantial financial aid from international donors, including governments and international organizations. This aid is crucial for supporting the Palestinian Authority and funding public services and development projects. Palestinians working abroad send money back to their families in Palestine. These remittances provide a significant source of income for many households.

International aid has been provided to Palestinians since at least the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. The Palestinians view the aid as keeping the Israeli–Palestinian peace process going, while Israelis and other foreign policy authorities have raised concerns that it is used to fund terrorism and removes the imperative for Palestinians to negotiate a settlement of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. As a provision of the Oslo Accords, international aid was to be provided to the Palestinians to ensure economic solvency for the Palestinian National Authority (PA). In 2004, it was reported that the PA, within the West Bank and Gaza Strip, receives one of the highest levels of aid in the world. In 2006, economic sanctions and other measures were taken by several countries against the PA, including suspension of international aid following Hamas' victory at the Palestinian Legislative Council election. Aid to the PA resumed in 2008 following the Annapolis Conference, where Hamas was not invited. Aid has been provided to the Palestinian Authority, Palestinian non-governmental organizations (PNGOs) as well as Palestinian political factions by various foreign governments, international organizations, international non-governmental organizations (INGOs), and charities, besides other sources.

The Rafah Border Crossing or Rafah Crossing Point is the sole crossing point between Egypt and Palestine's Gaza Strip. It is located on the Egypt–Palestine border. Under a 2007 agreement between Egypt and Israel, Egypt controls the crossing but imports through the Rafah crossing require Israeli approval.

Sara M. Roy is an American political economist and scholar. She is a Senior Research Scholar at the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at Harvard University.

A blockade has been imposed on the movement of goods and people in and out of the Gaza Strip since Hamas's takeover in 2007, led by Israel and supported by Egypt. The blockade's current stated aim is to prevent the smuggling of weapons into Gaza; previously stated motivations have included exerting economic pressure on Hamas. Human rights groups have called the blockade illegal and a form of collective punishment, as it restricts the flow of essential goods, contributes to economic hardship, and limits Gazans' freedom of movement. The blockade and its effects have led to the territory being called an "open-air prison".

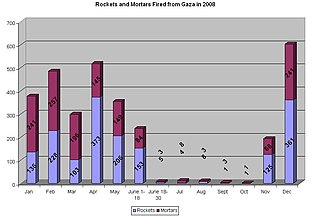

The 2008 Israel–Hamas ceasefire was an Egyptian-brokered six-month Tahdia "for the Gaza area", which went into effect between Hamas and Israel on 19 June 2008. According to the Egyptian-brokered agreement, Israel promised to stop air strikes and other attacks, while in return, there would not be rocket attacks on Israel from Gaza. Once the ceasefire held, Israel was to gradually begin to ease its blockade of Gaza.

The Protocol on Economic Relations, also called the Paris Protocol, was an agreement between Israel and the PLO, signed on 29 April 1994, and incorporated with minor amendments into the Oslo II Accord of September 1995.

Tourism in the Palestinian territories is tourism in East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip. In 2010, 4.6 million people visited the Palestinian territories, compared to 2.6 million in 2009. Of that number, 2.2 million were foreign tourists while 2.7 million were domestic. In the last quarter of 2012 over 150,000 guests stayed in West Bank hotels; 40% were European and 9% were from the United States and Canada. Major travel guides write that "the West Bank is not the easiest place in which to travel but the effort is richly rewarded."

The Gaza Mall is Gaza’s first shopping mall. It opened in Gaza City, State of Palestine, on the 17th of July 2010. It is the first mall that has been opened since the 2007 Hamas takeover of the Gaza Strip.

Egypt–Palestine relations are the bilateral relations between the Arab Republic of Egypt and the State of Palestine. Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser was a strong supporter of the Palestinian cause and he favored self-determination for the Palestinians. Although the Egyptian government has maintained a good relationship with Israel since the Camp David Accords, most Egyptians strongly resent Israel, and disapprove of the close relationship between the Israeli and Egyptian governments.

Hamas has governed the Gaza Strip in Palestine since its takeover of the region from rival party Fatah in June 2007. Hamas' government was led by Ismail Haniyeh from 2007 until February 2017, when Haniyeh was replaced as leader of Hamas in the Gaza Strip by Yahya Sinwar. As of November 2023, Yahya Sinwar continues to be the leader of Hamas in the Gaza Strip. In January 2024, due to the ongoing Israel–Hamas war, Israel said that Hamas lost control of most of the northern part of the Gaza Strip. In May 2024, Hamas regrouped in the north.

Israel–Palestine relations refers to the political, security, economical and other relations between the State of Israel and the State of Palestine. Israel and the PLO began to engage in the late 1980s and early 1990s in what became the Israeli–Palestinian peace process, culminated with the Oslo Accords in 1993. Shortly after, the Palestinian National Authority was established and during the next 6 years formed a network of economic and security connections with Israel, being referred to as a fully autonomous region with self-administration. In the year 2000, the relations severely deteriorated with the eruption of the Al-Aqsa Intifada – a rapid escalation of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. The events calmed down in 2005, with reconciliation and cease fire. The situation became more complicated with the split of the Palestinian Authority in 2007, the violent split of Fatah and Hamas factions, and Hamas' takeover of the Gaza Strip. The Hamas takeover resulted in a complete rift between Israel and the Palestinian faction in the Gaza Strip, cancelling all relations except limited humanitarian supply.

Reserves of natural gas were found offshore the Gaza Strip in the year 2000, within the framework of licensing to British Gas by the Palestinian National Authority. The discovered gas field Gaza Marine, though mediocre in size, had been considered at the time as one of the possible drives to boost Palestinian economy and promote regional cooperation.

The Electricity crisis in the Gaza Strip is an ongoing and growing electricity crisis faced by nearly two million residents of the Gaza Strip, with regular power supply being provided only for a few hours a day on a rolling blackout schedule. Some Gazans and government institutions use private electric generators, solar panels and uninterruptible power supply units to produce power when regular power is not available.