Education in Colombia includes nursery school, elementary school, high school, technical instruction and university education.

Education in Nepal has been modeled on the Indian system, which is in turn the legacy of the old British Raj. The National Examinations Board (NEB) supervises all standardized tests. The Ministry of Education is responsible for managing educational activities in Nepal. The National Center for Educational Development (NCED) is Nepal's teacher-training body.

Education in Montenegro is regulated by the Ministry of Education and Science of Government of Montenegro.

Education in Belarus is free at all levels except for higher education. The government ministry that oversees the running of the school systems is the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Belarus. Each of the regions inside Belarus has oversight of the education system, and students may attend either a public (state) or a private school. The current structure of the educational system was established by decree in 1994. The education system is also based on The Education Code of the Republic of Belarus and other educational standards.

Practically all children attend Quranic school for two or three years, starting around age five; there they learn the rudiments of the Islamic faith and some classical Arabic. When rural children attend these schools, they sometimes move away from home and help the teacher work his land.

Education in Kyrgyzstan is compulsory for nine years, between ages seven and 15. Following four years of primary and five years of lower secondary school, the system offers two years of upper secondary school, specialized secondary school, or vocational/technical school.

During Alfredo Stroessner Mattiauda’s presidency (1954–89), education initiatives took a backseat to economic concerns and the task of controlling political adversaries, and teacher salaries fell to extremely low levels. The constitution of 1992 attempted to remedy the long neglect of education. Article 85 of the constitution mandates that 20% of the government budget be designated for educational expenditures. This measure, however, has proven to be impractical and has been largely ignored.

Western-style education was introduced to Bhutan during the reign of Ugyen Wangchuck (1907–26). Until the 1950s, the only formal education available to Bhutanese students, except for private schools in Ha and Bumthang, was through Buddhist monasteries. In the 1950s, several private secular schools were established without government support, and several others were established in major district towns with government backing. By the late 1950s, there were twenty-nine government and thirty private primary schools, but only about 2,500 children were enrolled. Secondary education was available only in India. Eventually, the private schools were taken under government supervision to raise the quality of education provided. Although some primary schools in remote areas had to be closed because of low attendance, the most significant modern developments in education came during the period of the First Development Plan (1961–66), when some 108 schools were operating and 15,000 students were enrolled.

Education in Honduras is essential to the country of Honduras, for the maintenance, cultivation, and spread of culture and its benefits in Honduran society without discriminating against any particular group. The national education is secular and founded on the essential principles of democracy, inculcating and fomenting strong nationalist sentiments in the students and tying them directly to the economic and social development of the nation. Honduras's 1982 Constitution guarantees the right to education, a right also conveyed through the National Constituent Assembly's Decree 131 and in the official daily publication La Gaceta.

Education in St. Lucia is primarily based on the British education system and is provided in public and private schools.

The Ecuadorian Constitution requires that all children attend school until they achieve a “basic level of education,” which is estimated at nine school years.

Education in Georgia is free of charge and compulsory from the age of 6 until 17–18 years. In 1996, the gross primary enrollment rate was 88.2 percent, and the net primary enrollment rate was 87 percent; 48.8 percent are girls and 51.8 percent are boys. The constitution mandates that education is free. Related expenses that include textbooks and laptops are provided by the state free of charge; in 2001, there were 47,837 children not attending primary school.

Benin has abolished school fees and is carrying out the recommendations of its 2007 Educational Forum. In 2018, the net primary enrollment rate was 97 percent. Gross enrollment rate in secondary education has greatly increased in the last two decades, from 21.8 percent in 2000 to 59 percent in 2016, 67.1 percent in the case of males and 50.7 percent for females. Because of a rapid increase in the enrollment rate, the student/teacher ratio rose from 36:1 in 1990 to 53:1 in 1997 but has dropped again in the last years to 39:1 (2018). In 2018, the gross enrollment ratio in tertiary education was 12.5%.

Primary school education in Cape Verde is mandatory between the ages of 6–14 and free for children ages 6–12. In 1997, the gross primary enrollment rate was 148.8%. Primary school attendance rates were unavailable for Cape Verde as of 2001. While enrollment rates indicate a level of commitment to education, they do not always reflect children's participation in school. Textbooks have been made available to 90% of school children, and 90% of teachers have attended in-service teacher training. Its literacy rate as of 2010 ranges from 75 to 80%, the highest in West Africa south of the Sahara.

Public education in the Central African Republic is free, and education is compulsory from ages 6 to 14. AIDS-related deaths have taken a heavy toll on teachers, contributing to the closure of more than 100 primary schools between 1996 and 1998.

Primary education in Guinea is compulsory for 6 years. In 1997, the gross primary enrolment rate was 54.4 percent and the net primary enrolment rate was 41.8 percent. Public education in Guinea is governed by three ministries: The Ministry for Pre-University Education and Literacy; The Ministry for Technical Education and Occupational Training; and the Ministry for Higher Education, Scientific Research and Innovation.

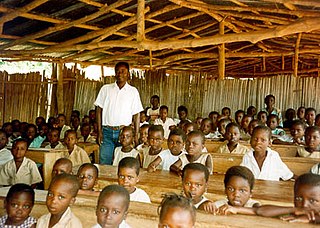

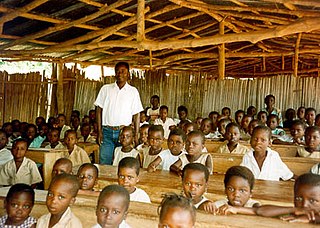

Education in Niger, as in other nations in the Sahelian region of Africa, faces challenges due to poverty and poor access to schools. Although education is compulsory between the ages of seven and fifteen, with primary and secondary school leading into optional higher education, Niger has one of the lowest literacy rates in the world. With assistance from external organizations, Niger has been pursuing educational improvement, reforming how schools utilize languages of instruction, and exploring how the system can close gender gaps in retention and learning.

Primary school education in Fiji is compulsory, and subsidized for eight years. In 1978, the gross primary enrollment ratio was 113.5 percent, and the net primary enrollment rate was 97.7 percent. As of 2009, attendance was decreasing due to security concerns and the burden of school fees, often due to the cost of transport. In 2013, the Bainimarama government made education at the primary and secondary level in Fiji free for all students. Fiji has since achieved universal access to primary education.

Universidad Empresarial de Costa Rica, also known as UNEM or Business University of Costa Rica, is a private university in the city of San José, Costa Rica. It is approved by the Consejo Nacional de Enseñanza Superior Universitaria Privada, the national council of higher education of Costa Rica, to award undergraduate degrees in accounting and business administration, and master's degrees in business administration.