Related Research Articles

Lipan Apache are a band of Apache, a Southern Athabaskan Indigenous people, who have lived in the Southwest and Southern Plains for centuries. At the time of European and African contact, they lived in New Mexico, Colorado, Oklahoma, Texas, and northern Mexico. Historically, they were the easternmost band of Apache.

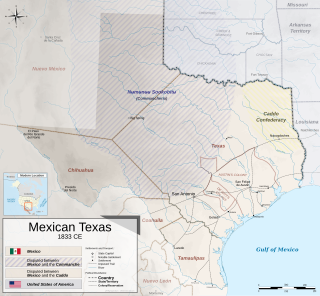

Mexican Texas is the historiographical name used to refer to the era of Texan history between 1821 and 1836, when it was part of Mexico. Mexico gained independence in 1821 after winning its war against Spain, which began in 1810. Initially, Mexican Texas operated similarly to Spanish Texas. Ratification of the 1824 Constitution of Mexico created a federal structure, and the province of Tejas was joined with the province of Coahuila to form the state of Coahuila y Tejas.

The Spanish Missions in Texas comprise the many Catholic outposts established in New Spain by Dominican, Jesuit, and Franciscan orders to spread their doctrine among Native Americans and to give Spain a toehold in the frontier land. The missions introduced European livestock, fruits, vegetables, and industry into the Texas area. In addition to the presidio and pueblo (town), the misión was one of the three major agencies employed by the Spanish crown to extend its borders and consolidate its colonial territories. In all, twenty-six missions were maintained for different lengths of time within the future boundaries of the state of Texas.

Guerrero is a city and seat of the municipality of Guerrero, in the north-eastern Mexican state of Coahuila. The 2010 census population was reported as 959 inhabitants.

Martín de Alarcón was the Governor of Coahuila and Spanish Texas from 1705 until 1708, and again from 1716 until 1719. He founded San Antonio, the first Spanish civilian settlement in Texas.

The Deadose were a Native American tribe in present-day Texas closely associated with the Jumano, Yojuane, Bidai and other groups living in the Rancheria Grande of the Brazos River in eastern Texas in the early 18th century.

Antonio de San Buenaventura y Olivares or simply Fray Antonio de Olivares was a Spanish Franciscan who officiated at the first Catholic Mass celebrated in Texas, and he was known for contributing to the founding of San Antonio and to the prior exploration of the area. He founded, among other missions, the Alamo Mission in San Antonio, the Presidio San Antonio de Bexar, and the Acequia Madre de Valero.

Presidio San Luis de las Amarillas, now better known as Presidio of San Sabá, was founded in April 1757 near present-day Menard, Texas, United States to protect the Mission Santa Cruz de San Sabá, established at the same time. The presidio and mission were built to secure Spain's claim to the territory. They were part of the treaty recently reached with the Lipan Apaches of the area for mutual aid against enemies. The early functioning of the mission and presidio were undermined by Hasinai, also allied with the Spanish, attacking the Apaches. The mission was located three miles downstream from the presidio by request of the monks at the mission to ensure that the Spanish soldiers would not be a corrupting influence on the Lipan Apaches the monks were trying to convert to Christianity. The original presidio and mission were built out of logs.

The Taovaya tribe of the Wichita people were Native Americans originally from Kansas, who moved south into Oklahoma and Texas in the 18th century. They spoke the Taovaya dialect of the Wichita language, a Caddoan language. Taovaya people today are enrolled in the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes, a federally recognized tribe headquartered in Anadarko, Oklahoma.

The Simono were an indigenous people who lived in what is now part of the Mexican state of Nuevo Leon and the U.S. state of Texas from at least the 16th century in the 18th century.

The Yojuane were a people who lived in Texas in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. They were closely associated with the Jumano and may have also been related to the Tonkawa. They have no connection to the Yowani in Texas, a Choctaw band.

Mission San Francisco Solano was a Spanish mission established March 1, 1700 by Franciscan missionaries. Along with Mission San Juan Bautista, Mission San Bernardo, and the nearby San Juan Bautista presidio, it belonged to a complex collectively known as the San Juan Bautista Missions.

The Mayeye were a Tonkawa language–speaking Native American people, who once lived in southeastern Texas. Coastal Mayeyes likely were absorbed into Karankawa communities. Inland Mayeyes likely joined larger Tonkawa communities.

El Cuilón, also known as Juan Rodriguez was a leader of the Ervipiame during the 18th century and, at least by Spanish standards, the overall leader of the Rancheria Grande, a large and numerous collection of Native American tribes between the Brazos River and the Colorado River in what is today eastern Texas in the United States.

The Xarames were an Indigenous people of the Americas of the San Antonio, Texas region. They were the dominant Native American group during the early history of Mission San Antonio de Valero. They were a Coahuiltecan people.

The Coahuiltecan were various small, autonomous bands of Native Americans who inhabited the Rio Grande valley in what is now northeastern Mexico and southern Texas. The various Coahuiltecan groups were hunter gatherers. First encountered by Europeans in the 16th century, their population declined due to European diseases, slavery, and numerous small-scale wars fought against the Spanish, criollo, Apache, and other Indigenous groups.

The Payaya people were Indigenous people whose territory encompassed the area of present-day San Antonio, Texas. The Payaya were a Coahuiltecan band and are the earliest recorded inhabitants of San Pedro Springs Park, the geographical area that became San Antonio.

Diego Ortiz Parrilla was an 18th-century Spanish military officer, governor, explorer, and cartographer.

Pedro de Aguirre was a Basque Spanish military man and explorer. He led the Espinosa-Olivares-Aguirre expedition in Texas.

The Sijame were an Indigenous people of the Americas of the San Antonio, Texas region. Some historians believe they were a band of Tonkawa, but they were likely a Coahuiltecan people.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Campbell, Thomas M. "Ervipiame Indians". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ↑ "Tribal and Band Groups". open.uapress.arizona.edu. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ↑ "Amistad NRA: American Indian Tribal Affiliation Study (Phase 1) (Chapter 2)". npshistory.com. Retrieved 13 August 2024.

- ↑ Barr, Peace Came in the Form of a Woman, p. 124–25.

- ↑ Barr, Peace Came in the Form of a Woman, p. 126

- ↑ Juliana Barr, Peace Came in the Form of a Woman: Indians and Spaniards in the Texas Borderlands (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), p. 133

- ↑ Elizabeth A. H. John, Storms Brewed in Other Men's Worlds: The Confrontation of Indians, Spanish and French in the Southwest, 1540-1795 (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1975), 277.

- ↑ Gary Clayton Anderson, The Indian Southwest, 1580-1830: Ethnogenesis and Reinvention (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999), 85.