A consumer is a person or a group who intends to order, or use purchased goods, products, or services primarily for personal, social, family, household and similar needs, who is not directly related to entrepreneurial or business activities. The term most commonly refers to a person who purchases goods and services for personal use.

The tertiary sector of the economy, generally known as the service sector, is the third of the three economic sectors in the three-sector model. The others are the primary sector and the secondary sector (manufacturing).

Consumerism is a social and economic order in which the aspirations of many individuals include the acquisition of goods and services beyond those necessary for survival or traditional displays of status. It emerged in Western Europe before the Industrial Revolution and became widespread around 1900. In economics, consumerism refers to policies that emphasize consumption. It is the consideration that the free choice of consumers should strongly inform the choice by manufacturers of what is produced and how, and therefore influence the economic organization of a society.

A service is an act or use for which a consumer, company, or government is willing to pay. Examples include work done by barbers, doctors, lawyers, mechanics, banks, insurance companies, and so on. Public services are those that society as a whole pays for. Using resources, skill, ingenuity, and experience, service provider's benefit service consumers. Services may be defined as intangible acts or performances whereby the service provider provides value to the customer.

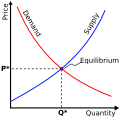

Information goods are commodities that provide value to consumers as a result of the information it contains and refers to any good or service that can be digitalized. Examples of information goods includes books, journals, computer software, music and videos. Information goods can be copied, shared, resold or rented. Information goods are durable and thus, will not be destroyed through consumption. As information goods have distinct characteristics as they are experience goods, have returns to scale and are non-rivalrous, the laws of supply and demand that depend on the scarcity of products do not frequently apply to information goods. As a result, the buying and selling of information goods differs from ordinary goods. Information goods are goods whose unit production costs are negligible compared to their amortized development costs. Well-informed companies have development costs that increase with product quality, but their unit cost is zero. Once an information commodity has been developed, other units can be produced and distributed at almost zero cost. For example, allow downloads over the Internet. Conversely, for industrial goods, the unit cost of production and distribution usually dominates. Firms with an industrial advantage do not incur any development costs, but unit costs increase as product quality improves.

Services marketing is a specialized branch of marketing which emerged as a separate field of study in the early 1980s, following the recognition that the unique characteristics of services required different strategies compared with the marketing of physical goods.

In Marxist philosophy, the term commodity fetishism describes the economic relationships of production and exchange as being social relationships that exist among things and not as relationships that exist among people. As a form of reification, commodity fetishism presents economic value as inherent to the commodities, and not as arising from the workforce, from the human relations that produced the commodity, the goods and the services.

Consumer behaviour is the study of individuals, groups, or organisations and all the activities associated with the purchase, use and disposal of goods and services. Consumer behaviour consists of how the consumer's emotions, attitudes, and preferences affect buying behaviour. Consumer behaviour emerged in the 1940–1950s as a distinct sub-discipline of marketing, but has become an interdisciplinary social science that blends elements from psychology, sociology, social anthropology, anthropology, ethnography, ethnology, marketing, and economics.

A prosumer is an individual who both consumes and produces. The term is a portmanteau of the words producer and consumer. Research has identified six types of prosumers: DIY prosumers, self-service prosumers, customizing prosumers, collaborative prosumers, monetised prosumers, and economic prosumers.

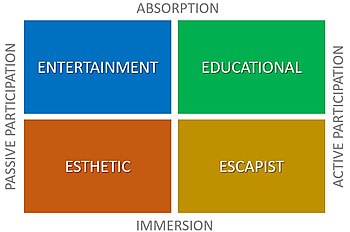

Engagement marketing is a marketing strategy that directly engages consumers and invites and encourages them to participate in the evolution of a brand or a brand experience. Rather than looking at consumers as passive receivers of messages, engagement marketers believe that consumers should be actively involved in the production and co-creation of marketing programs, developing a relationship with the brand.

In marketing, a company’s value proposition is the full mix of benefits or economic value which it promises to deliver to the current and future customers who will buy their products and/or services. It is part of a company's overall marketing strategy which differentiates its brand and fully positions it in the market. A value proposition can apply to an entire organization, parts thereof, customer accounts, or products and services.

Customer experience, sometimes abbreviated to CX, is the totality of cognitive, affective, sensory, and behavioral customer responses during all stages of the consumption process including pre-purchase, consumption, and post-purchase stages.

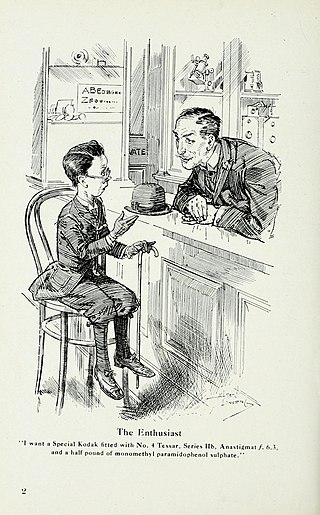

Emotional branding is a term used within marketing communication that refers to the practice of building brands that appeal directly to a consumer's emotional state, needs and aspirations. Emotional branding is successful when it triggers an emotional response in the consumer, that is, a desire for the advertised brand that cannot fully be rationalized. Emotional brands have a significant impact when the consumer experiences a strong and lasting attachment to the brand comparable to a feeling of bonding, companionship or love. Examples of emotional branding include the nostalgic attachment to the Kodak brand of film, bonding with the Jim Beam bourbon brand, and love for the McDonald's brand.

Experience management is an effort by organizations to measure and improve the experiences they provide to customers as well as stakeholders like vendors, suppliers, employees, and shareholders. The concept posits that experiences comprise distinct economic offerings that create economic value and competitive advantage.

The hedonic music consumption model was created by music researchers Kathleen Lacher and Richard Mizeski in 1994. Their goal was to use this model to examine the responses that listening to rock music creates, and to find if these responses influenced the listener's intention to later purchase the music. The article begins with a discussion of why the issue of music consumption is important. Music is then explored as an aesthetic product, prior to a discussion of what hedonic consumption is, as well as its origins, and concludes with an in-depth look at the model itself.

Experiential interior design (EID) is the practice of employing experiential or phenomenological values in interior experience design. EID is a human-centered design approach to interior architecture based on modern environmental psychology emphasizing human experiential needs. The notion of EID emphasizes the influence of the designed environments on human total experiences including sensorial, cognitive, emotional, social, and behavioral experiences triggered by environmental cues. One of the key promises of EID is to offer values beyond the functional or mechanical experiences afforded by the environment.

Employee experience design is the application of experience design in order to intentionally design HR products, services, events, and organizational environments with a focus on the quality of the employee experience whilst providing relevant solutions for an organization.

Massification is a strategy that some luxury companies use to expose their brands to a broader market and increase sales. As a method of implementing massification, companies have created diffusion lines. Diffusion lines are an offshoot of a company or a designer's original line that is less expensive in order to reach a broader market and gain a wider consumer base. Another strategy used in massification is brand extensions, which is when an already established company releases a new product under their name.

Consumer value is used to describe a consumer's strong relative preference for certain subjectively evaluated product or service attributes.

Economists and marketers use the Search, Experience, Credence (SEC) classification of goods and services, which is based on the ease or difficulty with which consumers can evaluate or obtain information. These days most economics and marketers treat the three classes of goods as a continuum. Archetypal goods are: