The Fairey Swordfish is a biplane torpedo bomber, designed by the Fairey Aviation Company. Originating in the early 1930s, the Swordfish, nicknamed "Stringbag", was principally operated by the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy. It was also used by the Royal Air Force (RAF), as well as several overseas operators, including the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and the Royal Netherlands Navy. It was initially operated primarily as a fleet attack aircraft. During its later years, the Swordfish was increasingly used as an anti-submarine and training platform. The type was in frontline service throughout the Second World War.

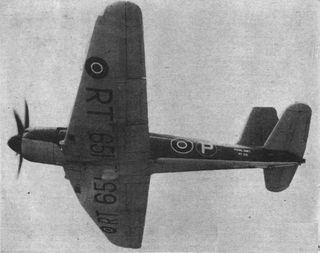

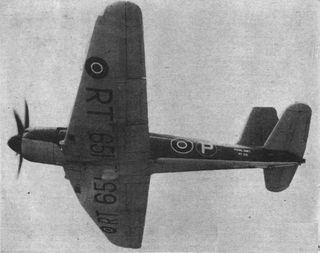

The de Havilland DH.103 Hornet, developed by de Havilland, was a fighter aircraft driven by two piston engines. It further exploited the wooden construction techniques that had been pioneered by the de Havilland Mosquito. Development of the Hornet had started during the Second World War as a private venture. The aircraft was to conduct long range fighter operations in the Pacific Theatre against the Empire of Japan but the war ended before the Hornet reached operational squadron status.

The Fairey Barracuda was a British carrier-borne torpedo and dive bomber designed by Fairey Aviation. It was the first aircraft of this type operated by the Royal Navy's Fleet Air Arm (FAA) to be fabricated entirely from metal.

The Grumman TBF Avenger is an American World War II-era torpedo bomber developed initially for the United States Navy and Marine Corps, and eventually used by several air and naval aviation services around the world.

The Aichi B7A Ryusei was a large and powerful carrier-borne torpedo-dive bomber produced by Aichi Kokuki for the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service during the Second World War. Built in only small numbers and deprived of the aircraft carriers it was intended to operate from, the type had little chance to distinguish itself in combat before the war ended in August 1945.

The Fairey Fulmar is a British carrier-borne reconnaissance aircraft/fighter aircraft which was developed and manufactured by aircraft company Fairey Aviation. It was named after the northern fulmar, a seabird native to the British Isles. The Fulmar served with the Royal Navy's Fleet Air Arm (FAA) during the Second World War.

The Fairey Albacore is a single-engine biplane torpedo bomber designed and produced by the British aircraft manufacturer Fairey Aviation. It was primarily operated by the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm (FAA) during the Second World War.

The Fairey Firefly is a Second World War-era carrier-borne fighter aircraft and anti-submarine aircraft that was principally operated by the Fleet Air Arm (FAA). It was developed and built by the British aircraft manufacturer Fairey Aviation Company.

The Bristol Type 163 Buckingham was a British Second World War medium bomber for the Royal Air Force (RAF). Overtaken by events, it was built in small numbers and was used primarily for transport and liaison duties.

The Blackburn Shark was a carrier-borne torpedo bomber designed and built by the British aviation manufacturer Blackburn Aircraft. It was originally known as the Blackburn T.S.R., standing for torpedo-spotter-reconnaissance, in reference to its intended roles. The Shark was the last of Blackburn's biplane torpedo bombers.

The Blackburn Firebrand was a British single-engine strike fighter for the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy designed during World War II by Blackburn Aircraft. Originally intended to serve as a pure fighter, its unimpressive performance and the allocation of its Napier Sabre piston engine by the Ministry of Aircraft Production for the Hawker Typhoon caused it to be redesigned as a strike fighter to take advantage of its load-carrying capability. Development was slow and the first production aircraft was not delivered until after the end of the war. Only a few hundred were built before it was withdrawn from front-line service in 1953.

The Fleet Air Arm Museum is devoted to the history of British naval aviation. It has an extensive collection of military and civilian aircraft, aero engines, models of aircraft and Royal Navy ships, and paintings and drawings related to naval aviation. It is located on RNAS Yeovilton airfield, and the museum has viewing areas where visitors can watch military aircraft take off and land. At the entrance to the museum are anchors from HMS Ark Royal and HMS Eagle, fleet carriers which served the Royal Navy until the 1970s. It is located 7 miles (11 km) north of Yeovil, and 40 miles (64 km) south of Bristol.

The Short Sturgeon was a planned British carrier-borne reconnaissance bomber whose development began during Second World War with the S.6/43 requirement for a high-performance torpedo bomber, which was later refined into the S.11/43 requirement which was won by the Sturgeon. With the end of the war in the Pacific production of the aircraft carriers from which the Sturgeon was intended to operate was suspended and the original reconnaissance bomber specification was cancelled.

The Blackburn B.48 Firecrest, given the SBAC designation YA.1, was a single-engine naval strike fighter built by Blackburn Aircraft for service with the British Fleet Air Arm during the Second World War. It was a development of the troubled Firebrand, designed to Air Ministry Specification S.28/43, for an improved aircraft more suited to carrier operations. Three prototypes were ordered with the company designation of B-48 and the informal name of "Firecrest", but only two of them actually flew. The development of the aircraft was prolonged by significant design changes and slow deliveries of components, but the determination by the Ministry of Supply in 1946 that the airframe did not meet the requirements for a strike fighter doomed the aircraft. Construction of two of the prototypes was continued to gain flight-test data and the third was allocated to strength testing. The two flying aircraft were sold back to Blackburn in 1950 for disposal and the other aircraft survived until 1952.

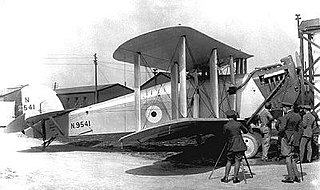

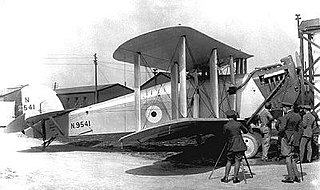

The Blackburn Dart was a carrier-based torpedo bomber biplane designed and manufactured by the British aviation company Blackburn Aircraft. It was the standard single-seat torpedo bomber operated by the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) between 1923 and 1933.

The Supermarine Type 322 was a prototype British carrier-borne torpedo, dive bomber and reconnaissance aircraft of the Second World War. A single-engined monoplane, it was unsuccessful, with only two examples being built. The Fairey Barracuda, built to the same specification, would fill this role.

The Curtiss XBTC was a prototype single-seat, single-engined torpedo/dive bomber developed during World War II for the United States Navy. Four aircraft were ordered, powered by two different engines, but the two aircraft to be fitted with the Wright R-3350 radial engine were cancelled in late 1942, leaving only the pair using the Pratt & Whitney R-4360 radial. By this time, Curtiss Aircraft was overwhelmed with work and the Navy gave the XBTC-2 prototypes a low priority which delayed progress so the first flight did not take place until the beginning of 1945. One aircraft crashed in early 1947 and the other was disposed of later that year.

The Curtiss XBT2C was a prototype two-seat, single-engined dive/torpedo bomber developed during World War II for the United States Navy. Derived from the Curtiss SB2C Helldiver dive bomber, it was an unsuccessful competitor to meet a 1945 Navy specification for an aircraft to combine the roles that previously required separate types. Unlike the other competitors, the XBT2C was designed to accommodate a radar operator.

826 Naval Air Squadron was a Fleet Air Arm aircraft squadron formed during World War II which has been reformed several times since then until last disbanded in 1993.