Corregidor is an island located at the entrance of Manila Bay in the southwestern part of Luzon in the Philippines, and is considered part of the Province of Cavite. Due to this location, Corregidor has historically been fortified with coastal artillery batteries to defend the entrance of Manila Bay and Manila itself from attacks by enemy warships. Located 48 kilometres (30 mi) inland, Manila is the nation's largest city and has been the most important seaport in the Philippines for centuries, from the colonial rule of Spain, Japan, and the United States, up through the establishment of the Third Philippine Republic in 1946.

The Harbor Defenses of Manila and Subic Bays were a United States Army Coast Artillery Corps harbor defense command, part of the Philippine Department of the United States Army from circa 1910 through early World War II. The command primarily consisted of four forts on islands at the entrance to Manila Bay and one fort on an island in Subic Bay.

Fort Mills was the location of US Major General George F. Moore's headquarters for the Philippine Department's Harbor Defenses of Manila and Subic Bays in early World War II, and was the largest seacoast fort in the Philippines. Most of this Coast Artillery Corps fort was built 1904–1910 by the United States Army Corps of Engineers as part of the Taft program of seacoast defense. The fort was named for Brigadier General Samuel Meyers Mills Jr., Chief of Artillery 1905–1906. It was the primary location of the Battle of Corregidor in the Japanese invasion of the Philippines in 1941–42, and of the recapture of Corregidor in February 1945, both in World War II.

Fort Hughes was built by the Philippine Department of the U.S. Army on Caballo Island in the Philippines in the early 1900s. The fort, which part of the Harbor Defenses of Manila and Subic Bays, was named for Major General Robert Patterson Hughes, a veteran of the American Civil War, Spanish–American War, and the Philippine–American War.

Fort Frank was one of the defense forts at the entrance to Manila Bay established by the United States. The entire island was designated as Fort Frank, in honor of Brigadier General Royal T. Frank, as part of the Harbor Defenses of Manila and Subic Bays built by the Philippine Department of the US Army in the early 1900s.

Fort Wint was part of the harbor defenses of Manila and Subic Bays built by the Philippine Department of the United States Army between 1907 and 1920 in response to recommendations of the Taft Board prior to the non-fortification clause of the Washington Naval Treaty. Fort Wint was located on Grande Island at the entrance of Subic Bay, approximately 35 miles (56 km) north of Manila Bay. The fort was named for Brigadier General Theodore J. Wint. As specified in the National Defense Act of 1935, this was one of the locations where coastal artillery training was conducted. A battery of the 60th Coast Artillery (AA) was stationed here.

Coastal artillery is the branch of the armed forces concerned with operating anti-ship artillery or fixed gun batteries in coastal fortifications.

The Battle of Corregidor, fought on 5–6 May 1942, was the culmination of the Japanese campaign for the conquest of the Commonwealth of the Philippines during World War II.

Several boards have been appointed by US presidents or Congress to evaluate the US defensive fortifications, primarily coastal defenses near strategically important harbors on the US shores, its territories, and its protectorates.

Battery Way was a battery of four 12-inch mortars located on the island of Corregidor. Battery Way was one of two mortar batteries at Fort Mills that, with Fort Hughes, Fort Drum, Fort Frank and Fort Wint formed the Harbor Defenses of Manila and Subic Bays. Battery Way was named for Lt. Henry N. Way of the 4th U.S. Artillery.

The 16 inch gun M1919 (406 mm) was a large coastal artillery piece installed to defend the United States' major seaports between 1920 and 1946. It was operated by the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps. Only a small number were produced and only seven were mounted; in 1922 and 1940 the US Navy surplussed a number of their own 16-inch/50 guns, which were mated to modified M1919 carriages and filled the need for additional weapons.

Seacoast defense was a major concern for the United States from its independence until World War II. Before airplanes, many of America's enemies could only reach it from the sea, making coastal forts an economical alternative to standing armies or a large navy. After the 1940s, it was recognized that fixed fortifications were obsolete and ineffective against aircraft and missiles. However, in prior eras foreign fleets were a realistic threat, and substantial fortifications were built at key locations, especially protecting major harbors.

The 12-inch coast defense mortar was a weapon of 12-inch (305 mm) caliber emplaced during the 1890s and early 20th century to defend US harbors from seaborne attack. In 1886, when the Endicott Board set forth its initial plan for upgrading the coast defenses of the United States, it relied primarily on mortars, not guns, to defend American harbors. Over the years, provision was made for fortifications that would mount some 476 of these weapons, although not all of these tubes were installed. Ninety-one of these weapons were remounted as railway artillery in 1918-1919, but this was too late to see action in World War I. The railway mortars were only deployed in small quantities, and none overseas. The fixed mortars in the Philippines saw action in the Japanese invasion in World War II. All of the fixed mortars in the United States were scrapped by 1944, as new weapons replaced them, and the railway mortars were scrapped after the war. Today, the only remaining mortars of this type in the 50 states are four at Battery Laidley, part of Fort Desoto near St. Petersburg, Florida, but the remains of coast defense mortar emplacements can be seen at many former Coast Artillery forts across the United States and its former territories. Additional 12-inch mortars and other large-caliber weapons remain in the Philippines.

The 8-inch gun M1888 (203 mm) was a U.S. Army Coast Artillery Corps gun, initially deployed 1898–1908 in about 75 fixed emplacements, usually on a disappearing carriage. During World War I, 37 or 47 of these weapons were removed from fixed emplacements or from storage to create a railway gun version, the 8-inch Gun M1888MIA1 Barbette carriage M1918 on railway car M1918MI, converted from the fixed coast defense mountings and used during World War I and World War II.

The U.S. Army Coast Artillery Corps (CAC) was an administrative corps responsible for coastal, harbor, and anti-aircraft defense of the United States and its possessions between 1901 and 1950. The CAC also operated heavy and railway artillery during World War I.

The 12-inch coastal defense gun M1895 (305 mm) and its variants the M1888 and M1900 were large coastal artillery pieces installed to defend major American seaports between 1895 and 1945. For most of their history they were operated by the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps. Most were installed on disappearing carriages, with early installations on low-angle barbette mountings. From 1919, 19 long-range two-gun batteries were built using the M1895 on an M1917 long-range barbette carriage. Almost all of the weapons not in the Philippines were scrapped during and after World War II.

The 59th Coast Artillery Regiment, later the 59th Air Defense Artillery Regiment, was a regiment in the United States Army. It served as a heavy artillery regiment in France in World War I, and was in the Battle of Corregidor, Philippine Islands, in World War II.

The 10-inch Gun M1895 (254 mm) and its variants the M1888 and M1900 were large coastal artillery pieces installed to defend major American seaports between 1895 and 1945. For most of their history they were operated by the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps. Most were installed on disappearing carriages, with early installations on barbette mountings. All of the weapons not in the Philippines were scrapped during World War II. Two of the surviving weapons were relocated from the Philippines to Fort Casey in Washington state in the 1960s.

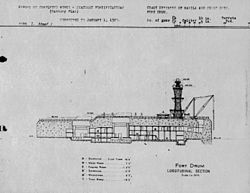

The 14-inch Gun M1907 (356 mm) and its variants the M1907MI, M1909, and M1910 were large coastal artillery pieces installed to defend major American seaports between 1895 and 1945. They were operated by the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps. Most were installed on single gun disappearing carriages; the only installation with four guns in twin turrets was built at the unique Fort Drum in Manila Bay, Philippines. All of the weapons not in the Philippines were scrapped during World War II.

The 6-inch gun M1897 (152 mm) and its variants the M1900, M1903, M1905, M1908, and M1 were coastal artillery pieces installed to defend major American seaports between 1897 and 1945. For most of their history they were operated by the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps. They were installed on disappearing carriages or pedestal mountings, and during World War II many were remounted on shielded barbette carriages. Most of the weapons not in the Philippines were scrapped within a few years after World War II.