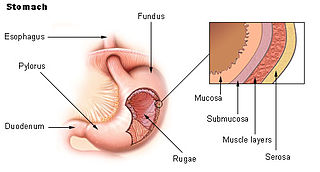

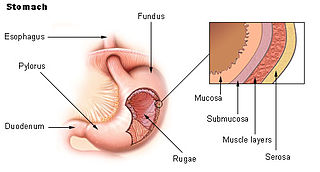

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the upper gastrointestinal tract of humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The stomach has a dilated structure and functions as a vital organ in the digestive system. The stomach is involved in the gastric phase of digestion, following the cephalic phase in which the sight and smell of food and the act of chewing are stimuli. In the stomach a chemical breakdown of food takes place by means of secreted digestive enzymes and gastric acid.

A mucous membrane or mucosa is a membrane that lines various cavities in the body of an organism and covers the surface of internal organs. It consists of one or more layers of epithelial cells overlying a layer of loose connective tissue. It is mostly of endodermal origin and is continuous with the skin at body openings such as the eyes, eyelids, ears, inside the nose, inside the mouth, lips, the genital areas, the urethral opening and the anus. Some mucous membranes secrete mucus, a thick protective fluid. The function of the membrane is to stop pathogens and dirt from entering the body and to prevent bodily tissues from becoming dehydrated.

The salivary glands in many vertebrates including mammals are exocrine glands that produce saliva through a system of ducts. Humans have three paired major salivary glands, as well as hundreds of minor salivary glands. Salivary glands can be classified as serous, mucous, or seromucous (mixed).

Mucus is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both serous and mucous cells. It is a viscous colloid containing inorganic salts, antimicrobial enzymes, immunoglobulins, and glycoproteins such as lactoferrin and mucins, which are produced by goblet cells in the mucous membranes and submucosal glands. Mucus serves to protect epithelial cells in the linings of the respiratory, digestive, and urogenital systems, and structures in the visual and auditory systems from pathogenic fungi, bacteria and viruses. Most of the mucus in the body is produced in the gastrointestinal tract.

The pyloruspyloric region or pyloric part connects the stomach to the duodenum. The pylorus is considered as having two parts, the pyloric antrum and the pyloric canal. The pyloric canal ends as the pyloric orifice, which marks the junction between the stomach and the duodenum. The orifice is surrounded by a sphincter, a band of muscle, called the pyloric sphincter. The word pylorus comes from Greek πυλωρός, via Latin. The word pylorus in Greek means "gatekeeper", related to "gate" and is thus linguistically related to the word "pylon".

Alkaline mucus is a thick fluid produced by animals which confers tissue protection in an acidic environment, such as in the stomach.

Gastric acid, gastric juice, or stomach acid is a digestive fluid formed within the stomach lining. With a pH between 1 and 3, gastric acid plays a key role in digestion of proteins by activating digestive enzymes, which together break down the long chains of amino acids of proteins. Gastric acid is regulated in feedback systems to increase production when needed, such as after a meal. Other cells in the stomach produce bicarbonate, a base, to buffer the fluid, ensuring a regulated pH. These cells also produce mucus – a viscous barrier to prevent gastric acid from damaging the stomach. The pancreas further produces large amounts of bicarbonate and secretes bicarbonate through the pancreatic duct to the duodenum to neutralize gastric acid passing into the digestive tract.

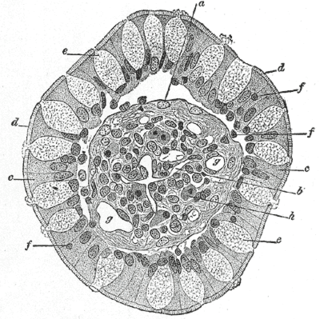

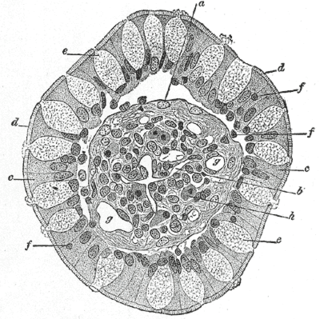

Parietal cells (also known as oxyntic cells) are epithelial cells in the stomach that secrete hydrochloric acid (HCl) and intrinsic factor. These cells are located in the gastric glands found in the lining of the fundus and body regions of the stomach. They contain an extensive secretory network of canaliculi from which the HCl is secreted by active transport into the stomach. The enzyme hydrogen potassium ATPase (H+/K+ ATPase) is unique to the parietal cells and transports the H+ against a concentration gradient of about 3 million to 1, which is the steepest ion gradient formed in the human body. Parietal cells are primarily regulated via histamine, acetylcholine and gastrin signalling from both central and local modulators.

Brunner's glands are compound tubuloalveolar submucosal glands found in that portion of the duodenum proximal to the hepatopancreatic sphincter.

Digestive enzymes take part in the chemical process of digestion, which follows the mechanical process of digestion. Food consists of macromolecules of proteins, carbohydrates, and fats that need to be broken down chemically by digestive enzymes in the mouth, stomach, pancreas, and duodenum, before being able to be absorbed into the bloodstream. Initial breakdown is achieved by chewing (mastication) and the use of digestive enzymes of saliva. Once in the stomach further mechanical churning takes place mixing the food with secreted gastric acid. Digestive gastric enzymes take part in some of the chemical process needed for absorption. Most of the enzymatic activity, and hence absorption takes place in the duodenum.

Goblet cells are simple columnar epithelial cells that secrete gel-forming mucins, like mucin 2 in the lower gastrointestinal tract, and mucin 5AC in the respiratory tract. The goblet cells mainly use the merocrine method of secretion, secreting vesicles into a duct, but may use apocrine methods, budding off their secretions, when under stress. The term goblet refers to the cell's goblet-like shape. The apical portion is shaped like a cup, as it is distended by abundant mucus laden granules; its basal portion lacks these granules and is shaped like a stem.

In human anatomy, there are three types of chief cells, the gastric chief cell, the parathyroid chief cell, and the type 1 chief cells found in the carotid body.

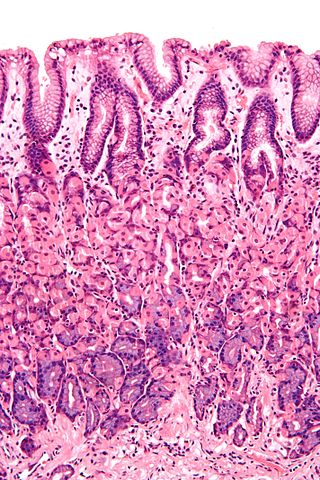

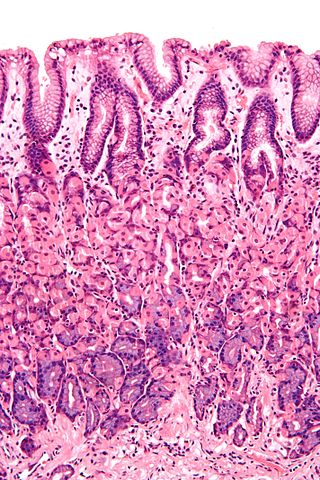

Gastric glands are glands in the lining of the stomach that play an essential role in the process of digestion. The gastric glands are located in gastric pits (foveolae) in the mucosa. The gastric mucosa is covered in surface mucous cells that produce the mucus necessary to protect the stomach epithelial lining from gastric acid secreted by the glands, and from pepsin a digestive enzyme. Surface mucous cells follow the indentations and partly line the gastric pits. Other mucus secreting cells are found in the necks of the glands. These are mucous neck cells that produce a different kind of mucus.

Gastric pits are indentations in the stomach which denote entrances to 3-5 tubular shaped gastric glands. They are deeper in the pylorus than they are in the other parts of the stomach. The human stomach has several million of these pits which dot the surface of the lining epithelium. Surface mucous cells line the pits themselves but give way to a series of other types of cells which then line the glands themselves.

The gastric mucosa is the mucous membrane layer of the stomach, which contains the gastric pits, to which the gastric glands empty. In humans, it is about one mm thick, and its surface is smooth, soft, and velvety. It consists of simple secretory columnar epithelium, an underlying supportive layer of loose connective tissue called the lamina propria, and the muscularis mucosae, a thin layer of muscle that separates the mucosa from the underlying submucosa.

Gastrointestinal physiology is the branch of human physiology that addresses the physical function of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The function of the GI tract is to process ingested food by mechanical and chemical means, extract nutrients and excrete waste products. The GI tract is composed of the alimentary canal, that runs from the mouth to the anus, as well as the associated glands, chemicals, hormones, and enzymes that assist in digestion. The major processes that occur in the GI tract are: motility, secretion, regulation, digestion and circulation. The proper function and coordination of these processes are vital for maintaining good health by providing for the effective digestion and uptake of nutrients.

The gastric mucosal barrier is the property of the stomach that allows it to safely contain the gastric acid required for digestion.

The proventriculus is part of the digestive system of birds. An analogous organ exists in invertebrates and insects.

The gastrointestinal wall of the gastrointestinal tract is made up of four layers of specialised tissue. From the inner cavity of the gut outwards, these are the mucosa, the submucosa, the muscular layer and the serosa or adventitia.

The human digestive system consists of the gastrointestinal tract plus the accessory organs of digestion. Digestion involves the breakdown of food into smaller and smaller components, until they can be absorbed and assimilated into the body. The process of digestion has three stages: the cephalic phase, the gastric phase, and the intestinal phase.