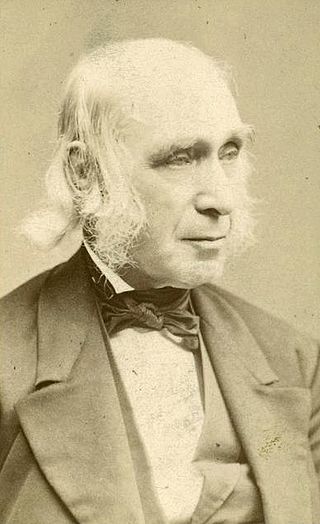

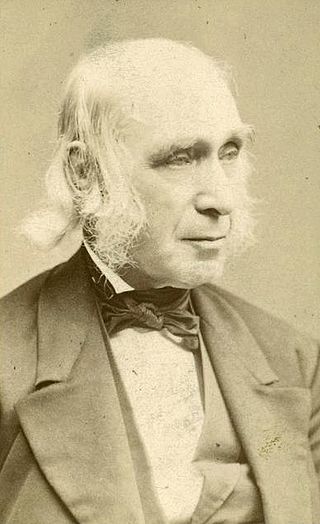

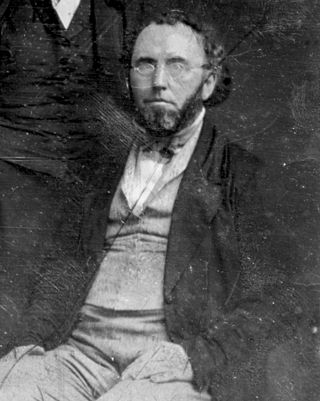

Amos Bronson Alcott was an American teacher, writer, philosopher, and reformer. As an educator, Alcott pioneered new ways of interacting with young students, focusing on a conversational style, and avoided traditional punishment. He hoped to perfect the human spirit and, to that end, advocated a plant-based diet. He was also an abolitionist and an advocate for women's rights.

Harvard is a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. The town is located 25 miles west-northwest of Boston, in eastern Massachusetts. A farming community settled in 1658 and incorporated in 1732, it has been home to several non-traditional communities, such as Harvard Shaker Village and the utopian transcendentalist center Fruitlands. It is also home to St. Benedict Abbey, a traditional Catholic monastery. It is a residential town noted for its public schools, with its students ranking high in the state's English and math examinations. The population was 6,851 at the 2020 census. The official seal of the town depicts the old town public library on The Common prior to renovations that removed the front steps.

Transcendentalism is a philosophical, spiritual, and literary movement that developed in the late 1820s and 1830s in the New England region of the United States. A core belief is in the inherent goodness of people and nature, and while society and its institutions have corrupted the purity of the individual, people are at their best when truly "self-reliant" and independent. Transcendentalists saw divine experience inherent in the everyday, rather than believing in a distant heaven. Transcendentalists saw physical and spiritual phenomena as part of dynamic processes rather than discrete entities.

Brook Farm, also called the Brook Farm Institute of Agriculture and Education or the Brook Farm Association for Industry and Education, was a utopian experiment in communal living in the United States in the 1840s. It was founded by former Unitarian minister George Ripley and his wife Sophia Ripley at the Ellis Farm in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, in 1841 and was inspired in part by the ideals of transcendentalism, a religious and cultural philosophy based in New England. Founded as a joint stock company, it promised its participants a portion of the farm's profits in exchange for an equal share of the work. Brook Farmers believed that by sharing the workload, they would have ample time for leisure and intellectual pursuits.

The Transcendental Club was a group of New England authors, philosophers, socialists, politicians and intellectuals of the early-to-mid-19th century which gave rise to Transcendentalism.

George Ripley was an American social reformer, Unitarian minister, and journalist associated with Transcendentalism. He was the founder of the short-lived Utopian community Brook Farm in West Roxbury, Massachusetts.

The Wayside is a historic house in Concord, Massachusetts. The earliest part of the home may date to 1717. Later it successively became the home of the young Louisa May Alcott and her family, who named it Hillside, author Nathaniel Hawthorne and his family, and children's writer Margaret Sidney. It became the first site with literary associations acquired by the National Park Service and is now open to the public as part of Minute Man National Historical Park.

Abigail "Abba" Alcott was an American activist for several causes and one of the first paid social workers in the state of Massachusetts. She was the wife of transcendentalist Amos Bronson Alcott and mother of four daughters, including Civil War novelist Louisa May Alcott.

Orchard House is a historic house museum in Concord, Massachusetts, United States, opened to the public on May 27, 1912. It was the longtime home of Amos Bronson Alcott (1799–1888) and his family, including his daughter Louisa May Alcott (1832–1888), who wrote and set her novel Little Women (1868–69) there.

Fruitlands Museum in Harvard, Massachusetts, is a museum about multiple visions of America on the site of the short-lived utopian community, Fruitlands. The museum includes the Fruitlands farmhouse, a museum about Shaker life, an art gallery with 19th-century landscape paintings, vernacular American portraits, and other changing exhibitions, and a museum of Native American history. In 2023, readers of USA Today voted to name Fruitlands as one of the ten best history museums in the United States.

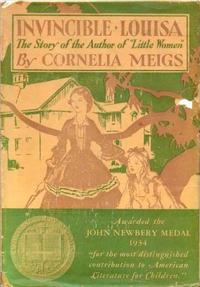

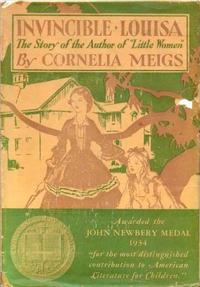

Invincible Louisa is a biography by Cornelia Meigs that won the Newbery Medal and the Lewis Carroll Shelf Award. It retells the life of Louisa May Alcott, author of Little Women.

The Concord School of Philosophy was a lyceum-like series of summer lectures and discussions of philosophy in Concord, Massachusetts from 1879 to 1888.

Charles Lane (1800–1870) was an English-American transcendentalist, abolitionist, and early voluntaryist. Along with Amos Bronson Alcott, he was one of the main founders of Fruitlands and a vegan.

Joseph Michael Palmer was a member of the Fruitlands commune and an associate of Louisa May Alcott and other Transcendentalists.

Ellen Sturgis Hooper was an American poet. A member of the Transcendental Club, she was widely regarded as one of the most gifted poets among the New England Transcendentalists. Her work is occasionally reprinted in anthologies.

Transcendental Wild Oats: A Chapter from an Unwritten Romance is a prose satire written by Louisa May Alcott, about her family's involvement with the Transcendentalist community Fruitlands in the early 1840s. The work was first published in a New York newspaper in 1873, and reprinted in 1874, 1876, and 1915 and after.

Alcott House in Ham, Surrey, was the home of a utopian spiritual community and progressive school which lasted from 1838 to 1848. Supporters of Alcott House, or the Concordium, were a key group involved in the formation of the Vegetarian Society in 1847.

Eden's Outcasts: The Story of Louisa May Alcott and Her Father is a 2007 biography by John Matteson of Louisa May Alcott, best known as the author of Little Women, and her father, Amos Bronson Alcott, an American transcendentalist philosopher and the founder of the Fruitlands utopian community. Eden's Outcasts won the 2008 Pulitzer Prize for Biography.

James Pierrepont Greaves, was an English mystic, educational reformer, socialist and progressive thinker who founded Alcott House, a short-lived utopian community and free school in Surrey. He described himself as a "sacred socialist" and was an advocate of vegetarianism and other health practices.

Thomas Treadwell Stone was an American Unitarian pastor, abolitionist, and Transcendentalist.