Related Research Articles

Antisemitism is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. This sentiment is a form of racism, and a person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Primarily, antisemitic tendencies may be motivated by negative sentiment towards Jews as a people or by negative sentiment towards Jews with regard to Judaism. In the former case, usually presented as racial antisemitism, a person's hostility is driven by the belief that Jews constitute a distinct race with inherent traits or characteristics that are repulsive or inferior to the preferred traits or characteristics within that person's society. In the latter case, known as religious antisemitism, a person's hostility is driven by their religion's perception of Jews and Judaism, typically encompassing doctrines of supersession that expect or demand Jews to turn away from Judaism and submit to the religion presenting itself as Judaism's successor faith—this is a common theme within the other Abrahamic religions. The development of racial and religious antisemitism has historically been encouraged by the concept of anti-Judaism, which is distinct from antisemitism itself.

Julius Streicher was a member of the Nazi Party, the Gauleiter of Franconia and a member of the Reichstag, the national legislature. He was the founder and publisher of the virulently antisemitic newspaper Der Stürmer, which became a central element of the Nazi propaganda machine. The publishing firm was financially very successful and made Streicher a multi-millionaire.

Karl Lueger was an Austrian lawyer and politician who served as Mayor of Vienna from 1897 until his death in 1910. He is credited with the transformation of Vienna into a modern city at the turn of the 20th century, although the populist and antisemitic politics of the Austrian Christian Social Party (CS), which he founded and led until his death, remain controversial, as they are sometimes viewed as a model for Adolf Hitler's Nazism.

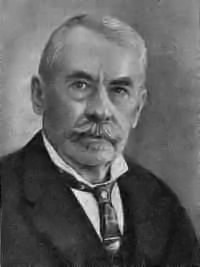

Theodor Fritsch was a German publisher and journalist. His antisemitic writings did much to influence popular German opinion against Jews in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His writings also appeared under the pen names Thomas Frey, Fritz Thor, and Ferdinand Roderich-Stoltheim.

The Christian Social Party was a right-wing political party in the German Empire founded in 1878 by Adolf Stoecker as the Christian Social Workers' Party.

Reinhold Wulle was a German Völkisch politician and publicist active during the Weimar Republic.

Otto Böckel was a German populist politician who became one of the first to successfully exploit antisemitism as a political issue in the country.

Alfred Roth was a German politician and writer noted for his anti-Semitism. He was sometimes known by his pseudonym Otto Arnim. Away from politics, he was a leading figure in the Commercial Employees Union.

Reichshammerbund was a German anti-Semitic movement founded in 1912 by Theodor Fritsch.

Max Liebermann von Sonnenberg was a German officer who became noted as an anti-Semitic politician and publisher. He was part of a wider campaign against German Jews that became a central feature of nationalist politics in Imperial Germany in the late nineteenth century.

Wilhelm Henning was a German military officer and right-wing politician.

Willibald Hentschel was a German writer and political agitator of the agrarian and volkisch movement. He sought to renew the Aryan race through a variety of schemes, including selective breeding and polygamy, all within a firmly rural setting.

The Economic Union was a parliamentary group in the German Empire's Reichstag, gathering deputies of several minor antisemitic and agrarian parties.

The German Social Party was an antisemitic and Völkisch political party in Germany and the Free City of Danzig during the Weimar Republic.

The German Reform Party was a far-right political party active in the German Empire. It had antisemitism as its ideological basis.

The German Social Reform Party was a German Empire antisemitic political party active from 1894 to 1900. It was a merger between the German Reform Party (DRP) and the German Social Party (DSP).

Oswald Franz Alexander Zimmermann was a German anti-Semitic politician and journalist. One of the leading representatives of political anti-Semitism in the German Empire, he was elected a member of the Reichstag three times.

Anti-antisemitism is opposition to antisemitism or prejudice against Jews, and just like the history of antisemitism, the history of anti-antisemitism is long and multifaceted. According to historian Omer Bartov, political controversies around antisemitism involve "those who see the world through an antisemitic prism, for whom everything that has gone wrong with the world, or with their personal lives, is the fault of the Jews; and those who see the world through an anti-antisemitic prism, for whom every critical observation of Jews as individuals or as a community, or, most crucially, of the state of Israel, is inherently antisemitic". It is disputed whether or not anti-antisemitism is synonymous with philosemitism, but anti-antisemitism often includes the "imaginary and symbolic idealization of ‘the Jew’" which is similar to philosemitism.

Zionist antisemitism or antisemitic Zionism refers to a phenomenon in which antisemites express support for Zionism and the State of Israel. In some cases, this support may be promoted for explicitly antisemitic reasons. Historically, this type of antisemitism has been most notable among Christian Zionists, who may perpetrate religious antisemitism while being outspoken in their support for Jewish sovereignty in Israel due to their interpretation of Christian eschatology. Similarly, people who identify with the political far-right, particularly in Europe and the United States, may support the Zionist movement because they seek to expel Jews from their country and see Zionism as the least complicated method of achieving this goal and satisfying their racial antisemitism.

Ferdinand Friedrich Karl Werner was a German schoolteacher and long-serving politician who held offices during the German Empire, the Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany. Throughout his career, he belonged to several far-right and antisemitic parties. He was a deputy in the Imperial Reichstag from 1911 to 1917, and again in the Republican Reichstag from 1924 to 1928. From 1921 to 1933, he served as a deputy of the Landtag of the People's State of Hesse. In the first year of Nazi Germany he was the first Nazi Party State President and, later, Minister-president of Hesse but was dismissed in a power struggle with Reichsstatthalter Jakob Sprenger. He then worked for the Association of German Mountain and Hiking Clubs and as a Hessian state historian.

References

- 1 2 3 Johannes Leicht; Arnulf Scriba (1 September 2016). "Deutschsoziale Partei (DSP) 1900-1914". LeMO – Lebendiges Museum Online. Deutsches Historisches Museum.

- 1 2 Richard S. Levy, Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution, ABC-CLIO, 2005, p. 422

- 1 2 3 Götz Aly, Why the Germans? Why the Jews?: Envy, Race Hatred, and the Prehistory of the Holocaust, Metropolitan Books, 2014, p. 81

- ↑ Christian Davis, Colonialism, Antisemitism, and Germans of Jewish Descent in Imperial Germany, University of Michigan Press, 2012, p. 12

- ↑ Davis, Colonialism, Antisemitism, and Germans of Jewish Descent in Imperial Germany, p. 26

- ↑ Davis, Colonialism, Antisemitism, and Germans of Jewish Descent in Imperial Germany, p. 33

- ↑ Davis, Colonialism, Antisemitism, and Germans of Jewish Descent in Imperial Germany, p. 34

- ↑ Davis, Colonialism, Antisemitism, and Germans of Jewish Descent in Imperial Germany, pp. 121-122

- ↑ Levy, Antisemitism, p. 290

- ↑ Matthew Lange, Antisemitic Elements in the Critique of Capitalism in German Culture, 1850-1933, Peter Lang, 2007, p. 118

- ↑ Davis, Colonialism, Antisemitism, and Germans of Jewish Descent in Imperial Germany, p. 47

- ↑ Levy, Antisemitism, p. 262

- ↑ Levy, Antisemitism, p. 297

- ↑ Davis, Colonialism, Antisemitism, and Germans of Jewish Descent in Imperial Germany, p. 123

- ↑ Levy, Antisemitism, p. 22

- ↑ Levy, Antisemitism, pp. 22-23

- ↑ Robert Melson, Revolution and Genocide: On the Origins of the Armenian Genocide and the Holocaust, University of Chicago Press, 1996, p. 118

- ↑ Geoff Eley, Reshaping the German Right: Radical Nationalism and Political Change After Bismarck, University of Michigan Press, 1991, p. 246

- 1 2 Rudy J. Koshar, Social Life, Local Politics, and Nazism: Marburg, 1880-1935, UNC Press Books, 2014, p. 71

- ↑ Detlef Mühlberger, Hitler's Voice: Organisation & Development of the Nazi Party, Peter Lang, 2004, pp. 239-240

- ↑ Larry Eugene Jones, The German Right in the Weimar Republic: Studies in the History of German Conservatism, Nationalism, and Antisemitism, Berghahn Books, 2014, p. 80