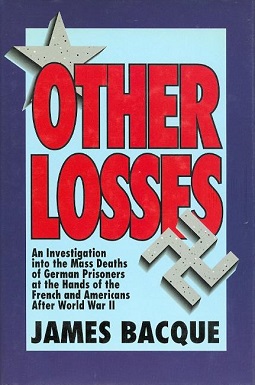

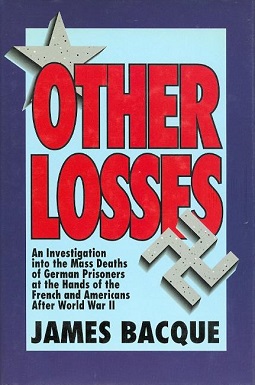

Other Losses is a 1989 book by Canadian writer James Bacque, which makes the claim that U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower intentionally caused the deaths by starvation or exposure of around a million German prisoners of war held in Western internment camps after the Second World War. Other Losses charges that hundreds of thousands of German prisoners that had fled the Eastern front were designated as "Disarmed Enemy Forces" in order to avoid recognition under the Geneva Convention (1929), for the purpose of carrying out their deaths through disease or slow starvation. Other Losses cites documents in the U.S. National Archives and interviews with people who stated they witnessed the events. The book claims that a "method of genocide" was present in the banning of Red Cross inspectors, the returning of food aid, soldier ration policy, and policy regarding shelter building.

World War II was the deadliest military conflict in history. An estimated total of 70–85 million people perished, or about 3% of the estimated global population of 2.3 billion in 1940. Deaths directly caused by the war are estimated at 50–56 million, with an additional estimated 19–28 million deaths from war-related disease and famine. Civilian deaths totaled 50–55 million. Military deaths from all causes totaled 21–25 million, including deaths in captivity of about 5 million prisoners of war. More than half of the total number of casualties are accounted for by the dead of the Republic of China and of the Soviet Union. The following tables give a detailed country-by-country count of human losses. Statistics on the number of military wounded are included whenever available.

The Rheinwiesenlager were a group of 19 camps built in the Allied-occupied part of Germany by the U.S. Army to hold captured German soldiers at the close of the Second World War. Officially named Prisoner of War Temporary Enclosures (PWTE), they held between one and almost two million surrendered Wehrmacht personnel from April until September 1945.

The Eastern Front was a theatre of World War II fought between the European Axis powers and Allies, including the Soviet Union (USSR) and Poland. It encompassed Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Northeast Europe (Baltics), and Southeast Europe (Balkans), and lasted from 22 June 1941 to 9 May 1945. Of the estimated 70–85 million deaths attributed to World War II, around 30 million occurred on the Eastern Front, including 9 million children. The Eastern Front was decisive in determining the outcome in the European theatre of operations in World War II, eventually serving as the main reason for the defeat of Nazi Germany and the Axis nations. It is noted by historian Geoffrey Roberts that "More than 80 per cent of all combat during the Second World War took place on the Eastern Front".

Hiwi, the German abbreviation of the word Hilfswilliger or, in English, auxiliary volunteer, designated, during World War II, a member of different kinds of voluntary auxiliary forces made up of recruits indigenous to the territories of Eastern Europe occupied by Nazi Germany. Adolf Hitler reluctantly agreed to allow recruitment of Soviet citizens in the Rear Areas during Operation Barbarossa. In a short period of time, many of them were moved to combat units.

Disarmed Enemy Forces is a US designation for soldiers who surrender to an adversary after hostilities end, and for those POWs who had already surrendered and were held in camps in occupied German territory at the time. It was General Dwight D. Eisenhower's designation of German prisoners in post–World War II occupied Germany.

Beniaminów is a village in Poland, administratively located in the Legionowo County in the Masovian Voivodeship. It is located east of Warsaw, between Legionowo and Nieporęt.

Forced labor of Germans in the Soviet Union was considered by the Soviet Union to be part of German war reparations for the damage inflicted by Nazi Germany on the Soviet Union during the Axis-Soviet campaigns (1941-1945) of World War II. Soviet authorities deported German civilians from Germany and Eastern Europe to the USSR after World War II as forced laborers, while ethnic Germans living in the USSR were deported during World War II and conscripted for forced labor. German prisoners of war were also used as a source of forced labor during and after the war by the Soviet Union and by the Western Allies.

Systematic POW labor in the Soviet Union is associated primarily with the outcomes of World War II and covers the period of 1939–1956, from the official formation of the first POW camps, to the repatriation of the last POWs, from the Kwantung Army.

Soviet prisoners of war (POWs) held by Nazi Germany and primarily in the custody of the German Army, were starved and subjected to deadly conditions. Of nearly six million that were captured, around 3 million died during their imprisonment.

Operation Solstice, also known as Unternehmen Husarenritt or the Stargard tank battle, was one of the last German armoured offensive operations on the Eastern Front in World War II.

World War II losses of the Soviet Union were about 27,000,000, both civilian and military from all war-related causes, although exact figures are disputed. A figure of 20 million was considered official during the Soviet era. The post-Soviet government of Russia puts the Soviet war losses at 26.6 million, on the basis of the 1993 study by the Russian Academy of Sciences, including people dying as a result of effects of the war. This includes 8,668,400 military deaths as calculated by the Russian Ministry of Defence.

Statistics for German World War II military casualties are divergent. The wartime military casualty figures compiled by the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht through January 31, 1945 are often cited by military historians in accounts of individual campaigns in the war. A study by German historian Rüdiger Overmans concluded that total German military deaths were much higher than those originally reported by the German High Command, amounting to 5.3 million, including 900,000 men conscripted from outside Germany's 1937 borders, in Austria and in east-central Europe. The German government reported that its records list 4.3 million dead and missing military personnel.

Heinrich Kittel was a German general during World War II who commanded the 462nd Infantry Division. As a prisoner of war, he was interned at Trent Park, where his conversations with fellow inmates were surreptitiously recorded by the British intelligence.

More than 2.8 million German soldiers surrendered on the Western Front between D-Day and the end of April 1945; 1.3 million between D-Day and March 31, 1945; and 1.5 million of them in the month of April. From early March, these surrenders seriously weakened the Wehrmacht in the West, and made further surrenders more likely, thus having a snowballing effect. On March 27, Dwight D. Eisenhower declared at a press conference that the enemy were a whipped army. In March, the daily rate of POWs taken on the Western Front was 10,000; in the first 14 days of April it rose to 39,000, and in the last 16 days the average peaked at 59,000 soldiers captured each day. The number of prisoners taken in the West in March and April was over 1,800,000, more than double the 800,000 German soldiers who surrendered to the Russians in the last three or four months of the war. One reason for this huge difference, possibly the most important, was that German forces facing the Red Army tended to fight to the end for fear of Soviet captivity whereas German forces facing the Western Allies tended to surrender without putting up much if any resistance. Accordingly, the number of Germans killed and wounded was much higher in the East than in the West.

The Golden Mile was an Allied POW camp in 1945 on the fertile Rhine plain known as the Golden Mile near Remagen in Germany.

Rüdiger Overmans is a German military historian who specializes in World War II history. His book German Military Losses in World War II, which he compiled as leader of a project sponsored by the Gerda Henkel Foundation, is one of the most comprehensive works about German casualties in World War II.

From the beginning of the Second World War, the Soviet policy—intended to discourage defection—advertised that any soldier who had fallen into enemy hands, or simply encircled without capture, was guilty of high treason and subject to execution, confiscation of property, and reprisal against their families. Issued in August 1941, Order No. 270 classified all commanders and political officers who surrendered as culpable deserters to be summarily executed and their families arrested. Sometimes Red Army soldiers were told that the families of defectors would be shot; although thousands were arrested, it is unknown if any such executions were carried out. As the war continued, Soviet leaders realized that most Soviet citizens had not voluntarily collaborated. In November 1944, the State Defense Committee decided that freed prisoners of war would be returned to the army while those who served in German military units or police would be handed over to the NKVD. At the Yalta Conference, the Western Allies agreed to repatriate Soviet citizens regardless of their wishes. The Soviet regime set up many NKVD filtration camps, hospitals, and recuperation centers for freed prisoners of war, where most stayed for an average of one or two months. These filtration camps were intended to separate out the minority of voluntary collaborators, but were not very effective.

Large numbers of German prisoners of war were held in Britain between the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939 and late 1948. Their numbers reached a peak of around 400,000 in 1946, and then began to fall when repatriation began. The experiences of these prisoners differed in certain important respects from those of captured German servicemen held by other nations. The treatment of the captives, though strict, was generally humane, and fewer prisoners died in British captivity than in other countries. The British government also introduced a programme of re-education, which was intended to demonstrate to the POWs the evils of the Nazi regime, while promoting the advantages of democracy. Some 25,000 German prisoners remained in the United Kingdom voluntarily after being released from prisoner of war status.

The NKVD special camp No. 48 was located in Cherntsy, Ivanovo Oblast. Russia. Initially it was established during World War II as a POW camp for most senior military commanders of the Axis powers. In German sources it is known as Kriegsgefangenenlager Woikowo, the latter location translated in English as Voikovo. Later it housed a secret Soviet biological weapons facility.