See also

This section contains information of unclear or questionable importance or relevance to the article's subject.(October 2023) |

Geschwind syndrome, also known as Gastaut-Geschwind, is a group of behavioral phenomena evident in some people with temporal lobe epilepsy. It is named for one of the first individuals to categorize the symptoms, Norman Geschwind, who published prolifically on the topic from 1973 to 1984. [1] There is controversy surrounding whether it is a true neuropsychiatric disorder. [2] Temporal lobe epilepsy causes chronic, mild, interictal (i.e. between seizures) changes in personality, which slowly intensify over time. [1] Geschwind syndrome includes five primary changes; hypergraphia, hyperreligiosity, atypical (usually reduced) sexuality, circumstantiality, and intensified mental life. [3] Not all symptoms must be present for a diagnosis. [2] Only some people with epilepsy or temporal lobe epilepsy show features of Geschwind syndrome. [4]

Hypergraphia is the tendency for extensive and compulsive writing or drawing, and has been observed in persons with temporal lobe epilepsy who have experienced multiple seizures. [5] Those with hypergraphia display extreme attention to detail in their writing. Some such patients keep diaries recording meticulous details about their everyday lives. In certain cases, these writings demonstrate extreme interest in religious topics. These individuals also tend to have poor penmanship. The great Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoyevsky, known to have epilepsy, showed signs of Geschwind syndrome, including hypergraphia. [6] In some cases hypergraphia can manifest with compulsive drawing. [7] Drawings by patients with hypergraphia exhibit repetition and a high level of detail, sometimes morphing writing with drawing. [8]

Some individuals may exhibit hyperreligiosity, characterized by increased, usually intense, religious feelings and philosophical interests, [9] and partial (temporal lobe) epilepsy patients experiencing frequent auras, perceived as numinous in character, exhibit greater ictal and interictal spirituality. [10] Some auras include ecstatic experiences. [11] It has been claimed that many religious leaders may exhibit this form of epilepsy. [12] [13] These religious feelings can motivate beliefs within any religion, including voodoun, [14] Christianity, Islam, [15] and others. Furthermore, "in someone from a strongly religious background hyperreligiosity might appear as deeply felt atheism". [16] [17] There are reports of patients converting between religions. [18] A few patients internalize their religious feelings: when asked if they are religious they say they are not. [19] One reviewer concluded that the evidence for a link between temporal lobe epilepsy and hyperreligiosity "isn't terribly compelling". [20]

People with Geschwind syndrome reported higher rates of atypical or altered sexuality. [21] In approximately half of affected individuals hyposexuality is reported. [22] [23] Less commonly, cases of hypersexuality have been reported. [24]

Individuals who demonstrate circumstantiality (or viscosity) tend to continue conversations for a long time and talk repetitively. [25]

Individuals may demonstrate an intensified mental life, including deepened cognitive and emotional responses. This tendency may pair with hypergraphia, leading to prolific creative output and a tendency toward intense, solitary pursuits.[ citation needed ]

This section contains information of unclear or questionable importance or relevance to the article's subject.(October 2023) |

Epilepsy is a group of non-communicable neurological disorders characterized by recurrent epileptic seizures. An epileptic seizure is the clinical manifestation of an abnormal, excessive, purposeless and synchronized electrical discharge in the brain cells called neurons. The occurrence of two or more unprovoked seizures defines epilepsy. The occurrence of just one seizure may warrant the definition in a more clinical usage where recurrence may be able to be prejudged. Epileptic seizures can vary from brief and nearly undetectable periods to long periods of vigorous shaking due to abnormal electrical activity in the brain. These episodes can result in physical injuries, either directly such as broken bones or through causing accidents. In epilepsy, seizures tend to recur and may have no immediate underlying cause. Isolated seizures that are provoked by a specific cause such as poisoning are not deemed to represent epilepsy. People with epilepsy may be treated differently in various areas of the world and experience varying degrees of social stigma due to the alarming nature of their symptoms.

Hypergraphia is a behavioral condition characterized by the intense desire to write or draw. Forms of hypergraphia can vary in writing style and content. It is a symptom associated with temporal lobe changes in epilepsy and in Geschwind syndrome. Structures that may have an effect on hypergraphia when damaged due to temporal lobe epilepsy are the hippocampus and Wernicke's area. Aside from temporal lobe epilepsy, chemical causes may be responsible for inducing hypergraphia.

A headache is often present in patients with epilepsy. If the headache occurs in the vicinity of a seizure, it is defined as peri-ictal headache, which can occur either before (pre-ictal) or after (post-ictal) the seizure, to which the term ictal refers. An ictal headache itself may or may not be an epileptic manifestation. In the first case it is defined as ictal epileptic headache or simply epileptic headache. It is a real painful seizure, that can remain isolated or be followed by other manifestations of the seizure. On the other hand, the ictal non-epileptic headache is a headache that occurs during a seizure but it is not due to an epileptic mechanism. When the headache does not occur in the vicinity of a seizure it is defined as inter-ictal headache. In this case it is a disorder autonomous from epilepsy, that is a comorbidity.

An aura is a perceptual disturbance experienced by some with epilepsy or migraine. An epileptic aura is a seizure.

In the field of neurology, temporal lobe epilepsy is an enduring brain disorder that causes unprovoked seizures from the temporal lobe. Temporal lobe epilepsy is the most common type of focal onset epilepsy among adults. Seizure symptoms and behavior distinguish seizures arising from the medial temporal lobe from seizures arising from the lateral (neocortical) temporal lobe. Memory and psychiatric comorbidities may occur. Diagnosis relies on electroencephalographic (EEG) and neuroimaging studies. Anticonvulsant medications, epilepsy surgery and dietary treatments may improve seizure control.

Frontal lobe epilepsy (FLE) is a neurological disorder that is characterized by brief, recurring seizures arising in the frontal lobes of the brain, that often occur during sleep. It is the second most common type of epilepsy after temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), and is related to the temporal form in that both forms are characterized by partial (focal) seizures.

The postictal state is the altered state of consciousness after an epileptic seizure. It usually lasts between 5 and 30 minutes, but sometimes longer in the case of larger or more severe seizures, and is characterized by drowsiness, confusion, nausea, hypertension, headache or migraine, and other disorienting symptoms.

Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) is a fatal complication of epilepsy. It is defined as the sudden and unexpected, non-traumatic and non-drowning death of a person with epilepsy, without a toxicological or anatomical cause of death detected during the post-mortem examination.

Epilepsy surgery involves a neurosurgical procedure where an area of the brain involved in seizures is either resected, ablated, disconnected or stimulated. The goal is to eliminate seizures or significantly reduce seizure burden. Approximately 60% of all people with epilepsy have focal epilepsy syndromes. In 15% to 20% of these patients, the condition is not adequately controlled with anticonvulsive drugs. Such patients are potential candidates for surgical epilepsy treatment.

Norman Geschwind was a pioneering American behavioral neurologist, best known for his exploration of behavioral neurology through disconnection models based on lesion analysis.

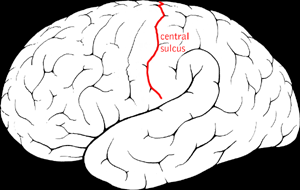

Benign Rolandic epilepsy or self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes is the most common epilepsy syndrome in childhood. Most children will outgrow the syndrome, hence the label benign. The seizures, sometimes referred to as sylvian seizures, start around the central sulcus of the brain.

In a 1927 letter to Sigmund Freud, Romain Rolland coined the phrase "oceanic feeling" to refer to "a sensation of 'eternity'", a feeling of "being one with the external world as a whole", inspired by the example of Ramakrishna, among other mystics. According to Rolland, this feeling is the source of all the religious energy that permeates in various religious systems, and one may justifiably call oneself religious on the basis of this oceanic feeling alone, even if one renounces every belief and every illusion. Freud discusses the feeling in his Future of an Illusion (1927) and Civilization and Its Discontents (1929). There he deems it a fragmentary vestige of a kind of consciousness possessed by an infant who has not yet differentiated themself from other people and things.

Spiritual crisis is a form of identity crisis where an individual experiences drastic changes to their meaning system typically because of a spontaneous spiritual experience. A spiritual crisis may cause significant disruption in psychological, social, and occupational functioning. Among the spiritual experiences thought to lead to episodes of spiritual crisis or spiritual emergency are psychiatric complications related to existential crisis, mystical experience, near-death experiences, Kundalini syndrome, paranormal experiences, religious ecstasy, or other spiritual practices.

Generally, seizures are observed in patients who do not have epilepsy. There are many causes of seizures. Organ failure, medication and medication withdrawal, cancer, imbalance of electrolytes, hypertensive encephalopathy, may be some of its potential causes. The factors that lead to a seizure are often complex and it may not be possible to determine what causes a particular seizure, what causes it to happen at a particular time, or how often seizures occur.

Migralepsy is a rare condition in which a migraine is followed, within an hour period, by an epileptic seizure. Because of the similarities in signs, symptoms, and treatments of both conditions, such as the neurological basis, the psychological issues, and the autonomic distress that is created from them, they individually increase the likelihood of causing the other. However, also because of the sameness, they are often misdiagnosed for each other, as migralepsy rarely occurs.

Febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES), is onset of severe seizures following a febrile illness in someone who was previously healthy. The seizures may initially be focal; however, often become tonic-clonic. Complications often include intellectual disability, behavioral problems, and ongoing seizures.

Drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE), also known as refractory epilepsy, intractable epilepsy, or pharmacoresistant epilepsy, is diagnosed following a failure of adequate trials of two tolerated and appropriately chosen and used antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) to achieve sustained seizure freedom. The probability that the next medication will achieve seizure freedom drops with every failed AED. For example, after two failed AEDs, the probability that the third will achieve seizure freedom is around 4%. Drug-resistant epilepsy is commonly diagnosed after several years of uncontrolled seizures, however, in most cases, it is evident much earlier. Approximately 30% of people with epilepsy have a drug-resistant form.

Hyperreligiosity is a psychiatric disturbance in which a person experiences intense religious beliefs or episodes that interfere with normal functioning. Hyperreligiosity generally includes abnormal beliefs and a focus on religious content or even atheistic content, which interferes with work and social functioning. Hyperreligiosity may occur in a variety of disorders including epilepsy, psychotic disorders and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Hyperreligiosity is a symptom of Geschwind syndrome, which is associated with temporal lobe epilepsy.

Fabrice Bartolomei is a French neurophysiologist, and University Professor at Aix-Marseille University (AMU), leading the Service de Neurophysiologie Clinique of the Timone Hospital at the Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Marseille, and he is the medical director of the ‘Centre Saint-Paul - Hopital Henri Gastaut’. He is the coordinator of the clinical network CINAPSE that is dedicated to the management of adult and pediatric cases of severe epilepsies and leader of the Federation Hospitalo-Universitaire Epinext. He is also member of the research unit Institut de Neurosciences des Systèmes](INS), UMR1106, Inserm - AMU.

Epilepsy patients with frequent numinous-like auras have greater ictal and interictal spirituality of an experiential, personalized, and atypical form, which may be distinct from traditional, culturally based religiosity.

Patients with ecstatic epileptic seizures report an altered consciousness, which they describe as a sense of heightened perception of themselves – they 'feel very present' – and an increased vividness of sensory perceptions.

Epileptic seizures have a historical association with religion, primarily through the concept of spirit possession. Five cases where epileptic seizures were initially attributed to Voodoo spirit possession are presented. The attribution is discussed within the context of the Voodoo belief system.

Studies that claim to show no difference in emotional makeup between temporal lobe and other epileptic patients (Guerrant et al., 1962; Stevens, 1966) have been reinterpreted (Blumer, 1975) to indicate that there is, in fact, a difference: those with temporal lobe epilepsy are more likely to have more serious forms of emotional disturbance. This 'typical personality' of temporal lobe epileptic patient has been described in roughly similar terms over many years (Blumer & Benson, 1975; Geschwind, 1975, 1977; Blumer, 1999; Devinsky & Schachter, 2009). These patients are said to have a deepening of emotions; they ascribe great significance to commonplace events. This can be manifested as a tendency to take a cosmic view; hyperreligiosity (or intensely professed atheism) is said to be common.

Although the patient denied being religious, his writings contained numerous religious references, and some pages were adorned with religious symbols.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)Men and women with epilepsy frequently complain, if asked, of sexual dysfunction and appear to have a higher incidence of sexual dysfunction than persons with other chronic neurologic illnesses.

... specific symptoms that characterize the Geschwind syndrome like hypergraphia and hyposexuality might be pathogenically related to hippocampal atrophy.