| Temporal lobe epilepsy | |

|---|---|

| |

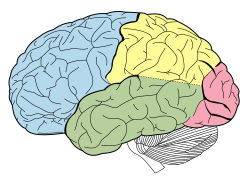

| Lobes of the brain. Temporal lobe in green | |

| Specialty | Neurology, Psychiatry |

In the field of neurology, temporal lobe epilepsy is an enduring brain disorder that causes unprovoked seizures from the temporal lobe. Temporal lobe epilepsy is the most common type of focal onset epilepsy among adults. [1] Seizure symptoms and behavior distinguish seizures arising from the mesial (medial) temporal lobe from seizures arising from the lateral (neocortical) temporal lobe. [2] Memory and psychiatric comorbidities may occur. Diagnosis relies on electroencephalographic (EEG) and neuroimaging studies. [3] [4] Anticonvulsant medications, epilepsy surgery, and dietary treatments may improve seizure control. [5] [6] [7] [8]

Contents

- Types

- Symptoms and behavior

- Mesial temporal lobe epilepsy

- Lateral temporal lobe epilepsy

- Comorbidities

- Memory

- Psychiatric comorbidities

- Personality

- Causes

- Risk factors

- Mechanisms

- Neuronal loss

- Neuron-specific type 2 K+/Cl− cotransporter (KCC2) mutation

- Granule cell dispersion

- Cortical developmental malformations

- Diagnosis

- Electroencephalogram

- Neuroimaging

- Treatment

- Medical treatment

- Surgical treatment

- Dietary treatment

- Remission

- See also

- Notes

- References