Sexual themes are frequently used in science fiction or related genres. Such elements may include depictions of realistic sexual interactions in a science fictional setting, a protagonist with an alternative sexuality, a sexual encounter between a human and a fictional extraterrestrial, or exploration of the varieties of sexual experience that deviate from the conventional.

Robert Baldwin Ross was a British journalist, art critic and art dealer, best known for his relationship with Oscar Wilde, to whom he was a devoted friend, lover, and literary executor. A grandson of the Canadian reform leader Robert Baldwin, and son of John Ross and Augusta Elizabeth Baldwin, Ross was a pivotal figure on the London literary and artistic scene from the mid-1890s to his early death, and mentored several literary figures, including Siegfried Sassoon. His open homosexuality, in a period when male homosexual acts were illegal, brought him many hardships.

East of Eden is a novel by American author and Nobel Prize winner John Steinbeck, published in September 1952. Many regard the work as Steinbeck's most ambitious novel, and Steinbeck himself considered it his magnum opus. Steinbeck said of East of Eden: "It has everything in it I have been able to learn about my craft or profession in all these years," and later said: "I think everything else I have written has been, in a sense, practice for this." Steinbeck originally addressed the novel to his young sons, Thom and John. Steinbeck wanted to describe the Salinas Valley for them in detail: the sights, sounds, smells and colors.

James Arthur Baldwin was an American writer and civil rights activist who garnered acclaim for his essays, novels, plays, and poems. His 1953 novel Go Tell It on the Mountain has been ranked among the best English-language novels. His 1955 essay collection Notes of a Native Son helped establish his reputation as a voice for human equality. Baldwin was a well-known public figure and orator, especially during the civil rights movement in the United States.

Countee Cullen was an American poet, novelist, children's writer, and playwright, particularly well known during the Harlem Renaissance.

The Good Soldier: A Tale of Passion is a 1915 novel by the British writer Ford Madox Ford. It is set just before World War I, and chronicles the tragedy of Edward Ashburnham and his seemingly perfect marriage, along with that of his two American friends. The novel is told using a series of flashbacks in non-chronological order, a literary technique that formed part of Ford's pioneering view of literary impressionism. Ford employs the device of the unreliable narrator to great effect, as the main character gradually reveals a version of events that is quite different from what the introduction leads the reader to believe. The novel was loosely based on two incidents of adultery and on Ford's messy personal life, specifically “the agonies Ford went through with his wife and his mistress in the six preceding years."

The Red and the Green is a novel by Iris Murdoch. Published in 1965, it was her ninth novel. It is set in Dublin during the week leading up to the Easter Rising of 1916, and is her only historical novel. Its characters are members of a complexly inter-related Anglo-Irish family who differ in their religious affiliations and in their views on the relations between England and Ireland.

The Kite Runner is the first novel by Afghan-American author Khaled Hosseini. Published in 2003 by Riverhead Books, it tells the story of Amir, a young boy from the Wazir Akbar Khan district of Kabul. The story is set against a backdrop of tumultuous events, from the fall of Afghanistan's monarchy through the Soviet invasion, the exodus of refugees to Pakistan and the United States, and the rise of the Taliban regime.

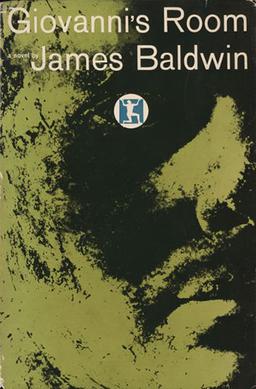

Giovanni's Room is a 1956 novel by James Baldwin. The book focuses on the events in the life of an American man living in Paris and his feelings and frustrations with his relationships with other men in his life, particularly an Italian bartender named Giovanni whom he meets at a Parisian gay bar.

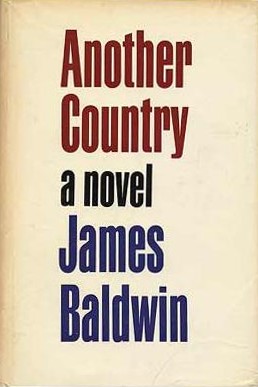

Another Country is a 1962 novel by James Baldwin. The novel is primarily set in Greenwich Village, Harlem, and France in the late 1950s. It portrayed many themes that were taboo at the time of its release, including bisexuality, interracial couples, and extramarital affairs.

The Postman Always Rings Twice is a 1946 American film noir directed by Tay Garnett and starring Lana Turner, John Garfield, and Cecil Kellaway. It is based on the 1934 novel of the same name by James M. Cain. This adaptation of the novel also features Hume Cronyn, Leon Ames and Audrey Totter. The musical score was written by George Bassman and Erich Zeisl.

Manhattan Transfer is an American novel by John Dos Passos published in 1925. It focuses on the development of urban life in New York City from the Gilded Age to the Jazz Age as told through a series of overlapping individual stories.

The Amen Corner is a three-act play by James Baldwin. It was Baldwin's first work for the stage following the success of his novel Go Tell It on the Mountain. The drama was first published in 1954, and inspired a short-lived 1983 Broadway musical adaptation with the slightly truncated title, Amen Corner. Anton Philips' production of The Amen Corner at The Tricycle Theatre in 1987 was the first black-produced and directed play to transfer to the West End of London. Phillips directed a revival of the play, again at The Tricycle, in 1999. The play was revived at the National Theatre in London in the summer of 2013.

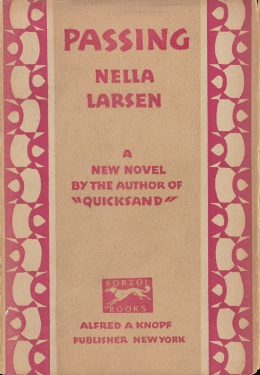

Passing is a novel by American author Nella Larsen, first published in 1929. Set primarily in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City in the 1920s, the story centers on the reunion of two childhood friends—Clare Kendry and Irene Redfield—and their increasing fascination with each other's lives. The title refers to the practice of "racial passing", which is a key element of the novel. Clare Kendry's attempt to pass as white for her husband, John (Jack) Bellew, is significant and is a catalyst for the tragic events.

Going to Meet the Man, published in 1965, is a collection of eight short stories by American writer James Baldwin. The book, dedicated "for Beauford Delaney", covers many topics related to anti-Black racism in American society, as well as African-American–Jewish relations, childhood, the creative process, criminal justice, drug addiction, family relationships, jazz, lynching, sexuality, and white supremacy.

Just Above My Head is James Baldwin's sixth and last novel, first published in 1979. He wrote it in his house in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France.

Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone is James Baldwin's fourth novel, first published in 1968.

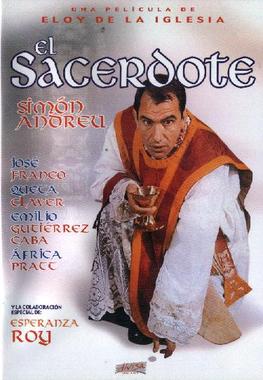

El Sacerdote is a 1978 Spanish film directed by Eloy de la Iglesia and starring Simón Andreu, Emilio Gutiérrez Caba and Esperanza Roy. The plot centres around a Catholic priest who suffers a personal crisis when his sexuality is suddenly awakened. Unable to reconcile his deep conservative religious faith with his sexual obsession, he spirals into a path of self-punishment. The script was first offered to Pilar Miró.

Pembroke (1894) is a novel written by Mary E. Wilkins Freeman. It is set in the small town of Pembroke, Massachusetts in the 1830s and 40s. The novel tells the story of a romance gone awry and the dramatic events that follow, which entertain the residents of the small town for years after. As one of Freeman's first novels, Pembroke experienced great success in its time and, although it has only recently experienced a comeback in the academic sphere, it is known for being an exemplary piece of New England local color fiction.

Go Tell It on the Mountain is a 1985 American made-for-television drama film directed by Stan Lathan, based on James Baldwin's 1953 novel of the same name. It stars Paul Winfield, Rosalind Cash, Ruby Dee, Alfre Woodard, Douglas Turner Ward, CCH Pounder, Kadeem Hardison, Giancarlo Esposito, and Ving Rhames in his first film role. The film was initially broadcast on the PBS television program American Playhouse on January 14, 1985.