The River Avon is a river in the southwest of England. To distinguish it from a number of other rivers of the same name, it is often called the Bristol Avon. The name 'Avon' is loaned from an ancestor of the Welsh word afon, meaning 'river'.

The Avon Gorge is a 1.5-mile (2.5-kilometre) long gorge on the River Avon in Bristol, England. The gorge runs south to north through a limestone ridge 1.5 miles (2.4 km) west of Bristol city centre, and about 3 miles (5 km) from the mouth of the river at Avonmouth. The gorge forms the boundary between the unitary authorities of North Somerset and Bristol, with the boundary running along the south bank. As Bristol was an important port, the gorge formed a defensive gateway to the city.

Henbury is a suburb of Bristol, England, approximately 5 miles (8.0 km) north west of the city centre. It was formerly a village in Gloucestershire and is now bordered by Westbury-on-Trym to the south; Brentry to the east and the Blaise Castle Estate, Blaise Hamlet and Lawrence Weston to the west. To the north lie the South Gloucestershire village of Hallen and the entertainment/retail park Cribbs Causeway.

The Severn Beach line is a local railway line in Bristol and Gloucestershire, England, which runs from Bristol Temple Meads to Severn Beach, and used to extend to Pilning. The first sections of the line were opened in 1863 as part of the Bristol Port Railway and Pier; the section through Bristol was opened in 1875 as the Clifton Extension Railway.

Blaise Castle is a folly built in 1766 near Henbury in Bristol, England. The castle sits within the Blaise Castle Estate, which also includes Blaise Castle House, a Grade II* listed 18th-century mansion house. The folly castle is also Grade II* listed and ancillary buildings including the orangery and dairy also have listings. Along with Blaise Hamlet, a group of nine small cottages around a green built in 1811 for retired employees, and various subsidiary buildings, the parkland is listed Grade II* on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens of special historic interest in England.

Shirehampton is a district of Bristol in England, near Avonmouth, at the northwestern edge of the city.

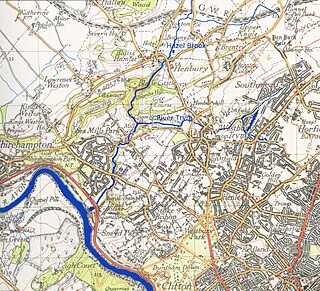

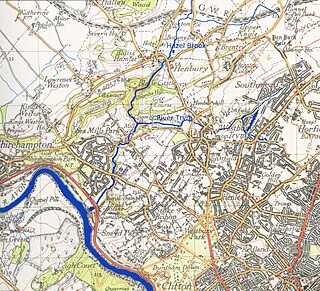

The River Trym is a short river, some 4.5 miles (7.2 km) in length, which rises in Filton, South Gloucestershire, England. The upper reaches are culverted, some underground, through mostly urban landscapes, but once it emerges into the open it flows through a nature reserve and city parks before joining the tidal River Avon at Sea Mills. 18th-century water mills near the mouth gave the area its name.

Lawrence Weston is a post-war housing estate in northwest Bristol, England, between Henbury and Shirehampton.

The Avonmouth Docks are part of the Port of Bristol, in England. They are situated on the northern side of the mouth of the River Avon, opposite the Royal Portbury Dock on the southern side, where the river joins the Severn estuary, within Avonmouth.

Sea Mills is a suburb of Bristol, England, 3.5 miles (6 km) north-west of the city centre, towards the seaward end of the Avon Gorge, between the former villages of Shirehampton to the west and Westbury-on-Trym and Stoke Bishop to the east, at the mouth of the River Trym where it joins the River Avon. Sea Mills was part of the city ward of Kingsweston. Following a Local Government Boundary Commission review in 2015, ward boundaries were redrawn and Sea Mills is now split between the Stoke Bishop ward and the Avonmouth and Lawrence Weston ward.

The English city of Bristol has a number of parks and public open spaces.

The city of Bristol, England, is divided into many areas, which often overlap or have non-fixed borders. These include Parliamentary constituencies, council wards and unofficial neighbourhoods. There are no civil parishes in Bristol.

Sea Mills railway station is on the Severn Beach Line and serves the district of Sea Mills and nearby Westbury on Trym in Bristol, England. It is 6 miles (9.7 km) from Bristol Temple Meads, situated at the confluence of the River Avon and River Trym and near the A4 Bristol Portway. Its three letter station code is SML. The station has a single platform which serves trains in both directions. As of 2015 it is managed by Great Western Railway, which is the third franchise to be responsible for the station since privatisation in 1997. They provide all train services at the station, mainly a train every 30 minutes in each direction.

Avonmouth railway station is located on the Severn Beach Line and serves the district of Avonmouth in Bristol, England. It is 9.0 miles (14.5 km) from Bristol Temple Meads. Its three letter station code is AVN. The station has two platforms, on either side of two running lines. As of 2015 it is managed by Great Western Railway, which is the third franchise to be responsible for the station since privatisation in 1997. They provide all train services at the station, mainly a train every 30 minutes to Bristol Temple Meads and one every hour to Severn Beach.

Hotwells is a district of the English port city of Bristol. It is located to the south of and below the high ground of Clifton, and directly to the north of the Floating Harbour. The southern entrance to the Avon Gorge, which connects the docks to the sea, lies at the western end of Hotwells. The eastern end of the area is at the roundabout where Jacobs Well Road meets Hotwell Road. Hotwells is split between the city wards of Clifton, and Hotwells and Harbourside.

Clifton Observatory is a former mill, now used as an observatory, located on Clifton Down, close to the Clifton Suspension Bridge, Bristol, England.

Kingsweston was a ward of the city of Bristol. The three districts in the ward were Coombe Dingle, Lawrence Weston and Sea Mills. The ward takes its name from the old district of Kings Weston, now generally considered part of Lawrence Weston. Following a Local Government Boundary Commission review in 2015 ward boundaries were redrawn and Kingsweston ward is now split between the Stoke Bishop ward and the Avonmouth and Lawrence Weston ward.

The Portway is a major road in the City of Bristol. It is part of the A4 and connects Bristol City Centre to the Avonmouth Docks and the M5 motorway via the Avon Gorge.

The Hazel Brook, also known as the Hen, is a tributary of the River Trym in Bristol, England. It rises at Cribbs Causeway in South Gloucestershire. From there, its course takes it south, passing the western end of Filton Aerodrome on its left bank, through Brentry and Henbury before dropping through a steep limestone gorge in the Blaise Castle estate. It continues south through two lakes before joining the Trym at Coombe Dingle.