The history of Sumer spans the 5th to 3rd millennia BCE in southern Mesopotamia, and is taken to include the prehistoric Ubaid and Uruk periods. Sumer was the region's earliest known civilization and ended with the downfall of the Third Dynasty of Ur around 2004 BCE. It was followed by a transitional period of Amorite states before the rise of Babylonia in the 18th century BCE.

Lagash was an ancient city state located northwest of the junction of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers and east of Uruk, about 22 kilometres (14 mi) east of the modern town of Al-Shatrah, Iraq. Lagash was one of the oldest cities of the Ancient Near East. The ancient site of Nina is around 10 km (6.2 mi) away and marks the southern limit of the state. Nearby Girsu, about 25 km (16 mi) northwest of Lagash, was the religious center of the Lagash state. The Lagash state's main temple was the E-ninnu at Girsu, dedicated to the god Ningirsu. The Lagash state incorporated the ancient cities of Lagash, Girsu, Nina.

Uru-ka-gina, Uru-inim-gina, or Iri-ka-gina was King of the city-states of Lagash and Girsu in Mesopotamia, and the last ruler of the 1st Dynasty of Lagash. He assumed the title of king, claiming to have been divinely appointed, upon the downfall of his corrupt predecessor, Lugalanda.

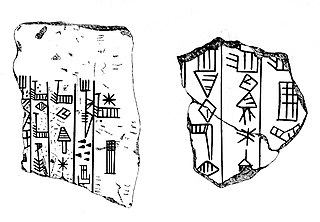

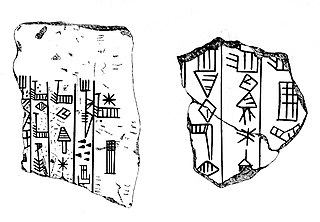

Ur-Nanshe also Ur-Nina, was the first king of the First Dynasty of Lagash in the Sumerian Early Dynastic Period III. He is known through inscriptions to have commissioned many buildings projects, including canals and temples, in the state of Lagash, and defending Lagash from its rival state Umma. He was probably not from royal lineage, being the son of Gunidu who was recorded without an accompanying royal title. He was the father of Akurgal, who succeeded him, and grandfather of Eanatum. Eanatum expanded the kingdom of Lagash by defeating Umma as illustrated in the Stele of the Vultures and continue building and renovation of Ur-Nanshe's original buildings.

Lugal-Zage-Si of Umma was the last Sumerian king before the conquest of Sumer by Sargon of Akkad and the rise of the Akkadian Empire, and was considered as the only king of the third dynasty of Uruk, according to the Sumerian King List. Initially, as king of Umma, he led the final victory of Umma in the generation-long conflict with the city-state Lagash for the fertile plain of Gu-Edin. Following up on this success, he then united Sumer briefly as a single kingdom.

Dudu was a 22nd-century BC king of the Akkadian Empire, who reigned for 21 years c. 2189-2169 BC according to the Sumerian king list. Unlike his two predecessors Naram-Sin and Shar-Kali-Sharri he was not deified.

Eannatum was a Sumerian Ensi of Lagash circa 2500–2400 BCE. He established one of the first verifiable empires in history, subduing Elam and destroying the city of Susa, and extending his domain over the rest of Sumer and Akkad. One inscription found on a boulder states that Eannatum was his Sumerian name, while his "Tidnu" (Amorite) name was Lumma.

Entemena, also called Enmetena, lived circa 2400 BC, was a son of En-anna-tum I, and he reestablished Lagash as a power in Sumer. He defeated Il, king of Umma, in a territorial conflict through an alliance with Lugal-kinishe-dudu of Uruk, successor to Enshakushanna, who is in the king list. The tutelary deity Shul-utula was his personal deity. His reign lasted at least 19 years.

Rimush c. 2279–2270 BC was the second king of the Akkadian Empire. He was the son of Sargon of Akkad and Queen Tashlultum. He was succeeded by his brother Manishtushu, and was an uncle of Naram-Sin of Akkad. Naram-Sin posthumously deified Sargon and Manishtushi but not his uncle. His sister was Enheduana, considered the earliest known named author in world history. Little is known about his brother Shu-Enlil. There was a city, Dur-Rimuš, located near Tell Ishchali and Khafajah. It was known to be a cult center of the storm god Adad.

Enshakushanna, or Enshagsagana, En-shag-kush-ana, Enukduanna, En-Shakansha-Ana, En-šakušuana was a king of Uruk around the mid-3rd millennium BC who is named on the Sumerian King List, which states his reign to have been 60 years. He conquered Hamazi, Akkad, Kish, and Nippur, claiming hegemony over all of Sumer.

Mesilim, also spelled Mesalim, was lugal (king) of the Sumerian city-state of Kish.

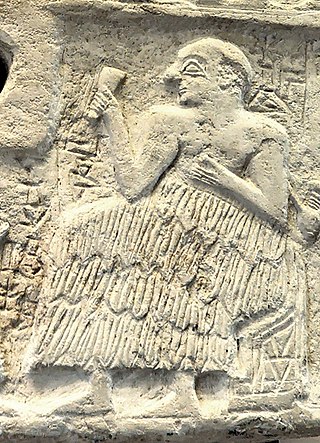

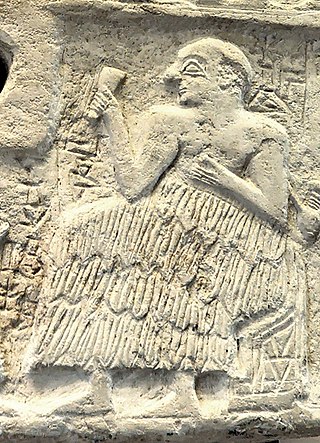

The Stele of the Vultures is a monument from the Early Dynastic IIIb period in Mesopotamia celebrating a victory of the city-state of Lagash over its neighbour Umma. It shows various battle and religious scenes and is named after the vultures that can be seen in one of these scenes. The stele was originally carved out of a single slab of limestone, but only seven fragments are known to have survived up to the present day. The fragments were found at Tello in southern Iraq in the late 19th century and are now on display in the Louvre. The stele was erected as a monument to the victory of king Eannatum of Lagash over Ush, king of Umma. It is the earliest known war monument.

Enakalle or Enakalli was the king of Umma circa 2500–2400 BC, a Sumerian city-state, during the Early Dynastic III period. His reign lasted at least 8 years.

Akurgal was the second king (Ensi) of the first dynasty of Lagash. His relatively short reign took place in the first part of the 25th century BCE, during the period of the archaic dynasties. He succeeded his father, Ur-Nanshe, founder of the dynasty, and was replaced by his son Eannatum.

Ush was King or ensi of Umma, a city-state in Sumer, circa 2450 BCE.

Ur-Lumma was a ruler of the Sumerian city-state of Umma, circa 2400 BCE. His father was King Enakalle, who had been vanquished by Eannatum of Lagash. Ur-Lumma claimed the title of "King" (Lugal). His reign lasted at least 12 years.

Lugalshaengur, , was ensi (governor) of the Sumerian city-state of Lagash.

Lugal-kinishe-dudu also Lugal-kiginne-dudu , was a King and (ensi) of Uruk and Ur who lived towards the end of the 25th century BCE. The Sumerian King List mentions Lugal-kinishe-dudu as the second king of the dynasty after En-shakansha-ana, attributing to him a fanciful reign of 120 years.

Enannatum II, son of Entemena, was Ensi (governor) of Lagash.

The Umma–Lagash war took place in Sumer's Early Dynastic III period (2600–2350 BCE) in present-day southern Iraq. It was caused by the city of Umma infringing upon an old border treaty with neighbouring city-state Lagash regarding a fertile piece of land coveted by both. It has also been nicknamed the Sumerian "Hundred Years War".