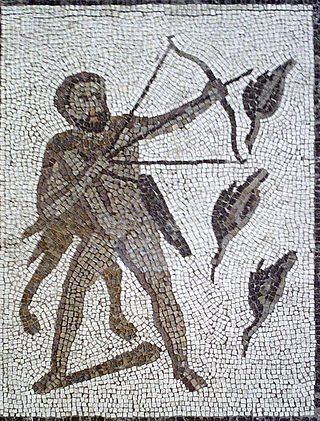

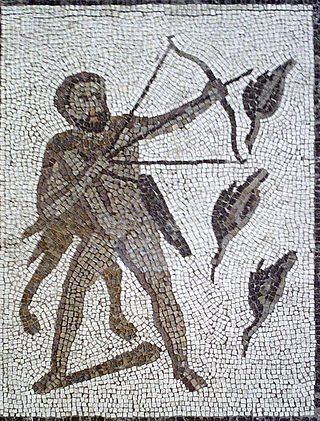

Hercules is the Roman equivalent of the Greek divine hero Heracles, son of Jupiter and the mortal Alcmena. In classical mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures.

Heracles, born Alcaeus or Alcides, was a divine hero in Greek mythology, the son of Zeus and Alcmene, and the foster son of Amphitryon. He was a descendant and half-brother of Perseus. He was the greatest of the Greek heroes, the ancestor of royal clans who claimed to be Heracleidae (Ἡρακλεῖδαι), and a champion of the Olympian order against chthonic monsters. In Rome and the modern West, he is known as Hercules, with whom the later Roman emperors, in particular Commodus and Maximian, often identified themselves. Details of his cult were adapted to Rome as well.

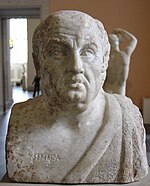

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger, usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, dramatist, and, in one work, satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

Deianira, Deïanira, or Deianeira, also known as Dejanira, is a Calydonian princess in Greek mythology whose name translates as "man-destroyer" or "destroyer of her husband". She was the wife of Heracles and, in late Classical accounts, his unwitting murderer, killing him with the poisoned Shirt of Nessus. She is the main character in Sophocles' play Women of Trachis.

In Greek mythology, Iole was the daughter of King Eurytus of Oechalia. According to the brief epitome in the Bibliotheca, Eurytus had a beautiful young daughter named Iole who was eligible for marriage. Iole was claimed by Heracles for a bride, but Eurytus refused her hand in marriage. Iole was indirectly the cause of Heracles' death because of his wife's jealousy of her.

In Greek mythology, Lichas was Heracles' servant, who brought the poisoned shirt from Deianira to Hercules because of Deianira's jealousy of Iole, which killed him.

In Greek mythology, Nessus was a famous centaur who was killed by Heracles, and whose poisoned blood in turn killed Heracles. He was the son of Centauros. He fought in the battle with the Lapiths and became a ferryman on the river Euenos.

In Greek mythology, the Shirt of Nessus, Tunic of Nessus, Nessus-robe, or Nessus' shirt was the poisoned shirt that killed Heracles. It was once a popular reference in literature. In folkloristics, it is considered an instance of the "poison dress" motif.

Women of Trachis or The Trachiniae c. 450–425 BC, is an Athenian tragedy by Sophocles.

Octavia is a Roman tragedy that focuses on three days in the year 62 AD during which Nero divorced and exiled his wife Claudia Octavia and married another. The play also deals with the irascibility of Nero and his inability to take heed of the philosopher Seneca's advice to rein in his passions.

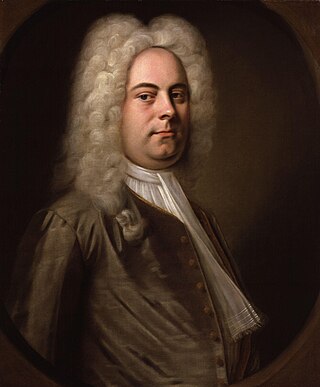

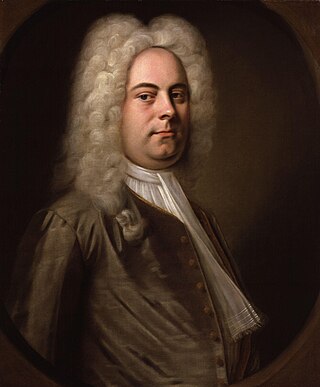

Hercules is a Musical Drama in three acts by George Frideric Handel, composed in July and August 1744. The English language libretto was by the Reverend Thomas Broughton, based on Sophocles's Women of Trachis and the ninth book of Ovid's Metamorphoses.

Hercules in the Underworld is the fourth television movie in the syndicated fantasy series Hercules: The Legendary Journeys.

The Capture of Oechalia is a fragmentary Greek epic that was variously attributed in Antiquity to either Homer or Creophylus of Samos; a tradition was reported that Homer gave the tale to Creophylus, in gratitude for guest-friendship (xenia), and that Creophylus wrote it down.

The tale known as "The Poison Dress" or "Embalmed Alive" features a dress that has in some way been poisoned. This is a recurring theme throughout legends and folktales of various cultures, including ancient Greece, Mughal India, and the United States. Although lacking evidence suggesting that some American urban legends are directly linked to the classical tales, they share several common motifs.

Déjanire is an opera in 4 acts composed by Camille Saint-Saëns to a libretto in French by Louis Gallet and Camille Saint-Saëns. The last of Saint-Saëns' operas, it premiered on 28 August 1898 in the new arènes in Beziers. One of the opera's central characters, Hercule (Hercules), had been the subject of two earlier symphonic poems by Saint-Saëns – Le Rouet d'Omphale (1872) and La Jeunesse d'Hercule (1877). The story is based on The Trachiniae by Sophocles.

Goliath and the Dragon is a 1960 international co-production sword-and-sandal film starring Mark Forest and Broderick Crawford. The name of the main character was changed from Hercules to Emilius for release in North America by American International Pictures to sell it as a sequel to their earlier Goliath and the Barbarians (1959).

The Stymphalian birds are a group of voracious birds in Greek mythology. The birds' appellation is derived from their dwelling in a swamp in Stymphalia.

Hercule mourant is an opera by the French composer Antoine Dauvergne, first performed at the Académie Royale de Musique on 3 April 1761. It takes the form of a tragédie lyrique in five acts. The libretto, by Jean-François Marmontel, is based on the tragedies The Women of Trachis by Sophocles and Hercule mourant, ou La Déjanire (1634) by Jean Rotrou.

Thyestes is a first century AD fabula crepidata of approximately 1112 lines of verse by Lucius Annaeus Seneca, which tells the story of Thyestes, who unwittingly ate his own children who were slaughtered and served at a banquet by his brother Atreus. As with most of Seneca's plays, Thyestes is based upon an older Greek version with the same name by Euripides.

Agamemnon is a fabula crepidata of c. 1012 lines of verse written by Lucius Annaeus Seneca in the first century AD, which tells the story of Agamemnon, who was killed by his wife Clytemnestra in his palace after his return from Troy.