Cymbeline, also known as The Tragedie of Cymbeline or Cymbeline, King of Britain, is a play by William Shakespeare set in Ancient Britain and based on legends that formed part of the Matter of Britain concerning the early Celtic British King Cunobeline. Although it is listed as a tragedy in the First Folio, modern critics often classify Cymbeline as a romance or even a comedy. Like Othello and The Winter's Tale, it deals with the themes of innocence and jealousy. While the precise date of composition remains unknown, the play was certainly produced as early as 1611.

Matteo Bandello was an Italian writer, soldier, monk, and, later, a Bishop mostly known for his novellas. His collection of 214 novellas made him the most popular short-story writer of his day.

Béatrice et Bénédict is an opéra comique in two acts by French composer Hector Berlioz. Berlioz wrote the French libretto himself, based in general outline on a subplot in Shakespeare's Much Ado About Nothing.

Much Ado About Nothing is a 1993 romantic comedy film based on William Shakespeare's play of the same name. Kenneth Branagh, who adapted the play for the screen and directed it, also stars in the film, which features Emma Thompson, Robert Sean Leonard, Denzel Washington, Michael Keaton, Keanu Reeves, and Kate Beckinsale in her film debut.

Elizabeth Rex is a play by Timothy Findley. It premiered in a 2000 production by the Stratford Festival. The play won the 2000 Governor General's Award for English language drama.

Dogberry is a character created by William Shakespeare for his play Much Ado About Nothing. The Nuttall Encyclopædia describes him as a "self-satisfied night constable" with an inflated view of his own importance as the leader of a group of comically bumbling watchmen. Dogberry is notable for his numerous malapropisms, sometimes called "dogberryisms" or "dogberrys". The character was created for William Kempe, who played comic roles in Shakespeare's theatre company the Lord Chamberlain's Men.

ShakespeaRe-Told is the umbrella title for a series of four television adaptations of William Shakespeare's plays broadcast on BBC One during November 2005. In a similar manner to the 2003 production of The Canterbury Tales, each play is adapted by a different writer, and relocated to the present day. The plays were produced in collaboration by BBC Northern Ireland and the central BBC drama department. In August 2006 the four films aired on BBC America.

A ghost character, in the bibliographic or scholarly study of texts of dramatic literature, is a term for an inadvertent error committed by the playwright in the act of writing. It is a character who is mentioned as appearing on stage, but who does not do anything, and who seems to have no purpose. As Kristian Smidt put it, they are characters that are "introduced in stage directions or briefly mentioned in dialogue who have no speaking parts and do not otherwise manifest their presence". It is generally interpreted as an author's mistake, indicative of an unresolved revision to the text. If the character was intended to appear and say nothing, it is assumed this would be made clear in the playscript.

Emily "Eve" Best is an English actress and director. She is known for her television roles as Dr. Eleanor O'Hara in the Showtime series Nurse Jackie (2009–2013), First Lady Dolley Madison in the American Experience television special (2011), and Monica Chatwin in the BBC miniseries The Honourable Woman (2014). She also played Wallis Simpson in the 2010 film The King's Speech.

Much Ado About Nothing is a comedy by William Shakespeare thought to have been written in 1598 and 1599. The play was included in the First Folio, published in 1623.

From its premiere at the turn of the 17th century, Hamlet has remained Shakespeare's best-known, most-imitated, and most-analyzed play. The character of Hamlet played a critical role in Sigmund Freud's explanation of the Oedipus complex. Even within the narrower field of literature, the play's influence has been strong. As Foakes writes, "No other character's name in Shakespeare's plays, and few in literature, have come to embody an attitude to life ... and been converted into a noun in this way."

The Riverside Shakespeare is a long-running series of editions of the complete works of William Shakespeare published by the Houghton Mifflin company.

Much Ado About Nothing is an opera in four acts by Charles Villiers Stanford, to a libretto by Julian Sturgis based on Shakespeare's play Much Ado About Nothing. It was the composer's seventh completed opera.

Viel Lärm um nichts is an East German film based on William Shakespeare's play Much Ado About Nothing. It was released in 1964.

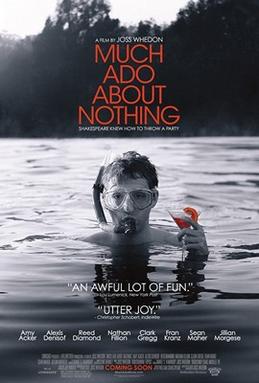

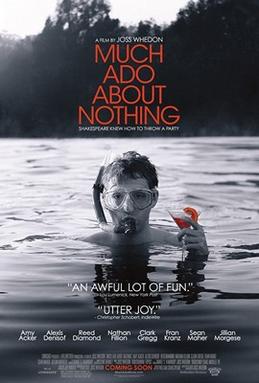

Much Ado About Nothing is a 2012 American romantic comedy film written, produced, directed, edited, and composed by Joss Whedon, based on William Shakespeare's play of the same name. The film stars Amy Acker, Alexis Denisof, Nathan Fillion, Clark Gregg, Reed Diamond, Fran Kranz, Sean Maher, and Jillian Morgese.

"Hoist with his own petard" is a phrase from a speech in William Shakespeare's play Hamlet that has become proverbial. The phrase's meaning is that a bomb-maker is blown off the ground by his own bomb ("petard"), and indicates an ironic reversal or poetic justice.

Don Pedro, Prince of Aragon, is a fictional character from William Shakespeare's play Much Ado About Nothing. In the play, Don Pedro is a nobleman who visits his friend Leonato in Messina, Italy, after a successful military conquest. Don Pedro helps Claudio to woo Hero and helps set up Benedick and Beatrice who together form the two key couples in the play.

Imogen Says Nothing: The Annotated Life of Imogen of Messina, last sighted in the First Folio of William Shakespeare's Much Adoe About Nothing is a three-act play by Aditi Brennan Kapil inspired by a ghost character in Shakespeare's Much Ado About Nothing. The play premiered on January 20, 2017 at the Yale Repertory Theatre.

Much Ado About Nothing is a 1973 Soviet romantic comedy film directed by Samson Samsonov based on William Shakespeare's play of the same name.

Beatrice is a fictional character in William Shakespeare's play Much Ado About Nothing. In the play, she is the niece of Leonato and the cousin of Hero. Atypically for romantic heroines of the sixteenth century, she is feisty and sharp-witted; these characteristics have led some scholars to label Beatrice a protofeminist character. During the play, she is tricked into falling in love with Benedick, a soldier with whom she has a "merry war", after rumours are spread that they are in love with each other.