Shiva, also known as Mahadeva is one of the principal deities of Hinduism. He is the Supreme Being in Shaivism, one of the major traditions within Hinduism.

Hindu mythology is the body of myths attributed to, and espoused by, the adherents of the Hindu religion, found in Sanskrit texts such as the Vedic literature, epics like Mahabharata and Ramayana, the Puranas, and mythological stories specific to a particular ethnolinguistic group like the Tamil Periya Puranam and Divya Prabandham, and the Mangal Kavya of Bengal. Hindu myths are also found in widely translated popular texts such as the fables of the Panchatantra and the Hitopadesha, as well as in Southeast Asian texts.

Hindu deities are the gods and goddesses in Hinduism. Deities in Hinduism are as diverse as its traditions, and a Hindu can choose to be polytheistic, pantheistic, monotheistic, monistic, even agnostic, atheistic, or humanist. The terms and epithets for deities within the diverse traditions of Hinduism vary, and include Deva, Devi, Ishvara, Ishvari, Bhagavān and Bhagavati.

Bhakti is a term common in Indian religions which means attachment, fondness for, devotion to, trust, homage, worship, piety, faith, or love. In Indian religions, it may refer to loving devotion for a personal God, a formless ultimate reality or for an enlightened being. Bhakti is often a deeply emotional devotion based on a relationship between a devotee and the object of devotion.

In Buddhism, Avalokiteśvara, also known as Lokeśvara and Chenrezig, is a tenth-level bodhisattva associated with great compassion (mahakaruṇā). He is often associated with Amitabha Buddha. Avalokiteśvara has numerous manifestations and is depicted in various forms and styles. In some texts, he is even considered to be the source of all Hindu deities.

Shaivism is one of the major Hindu traditions, which worships Shiva as the Supreme Being. One of the largest Hindu denominations, it incorporates many sub-traditions ranging from devotional dualistic theism such as Shaiva Siddhanta to yoga-orientated monistic non-theism such as Kashmiri Shaivism. It considers both the Vedas and the Agama texts as important sources of theology. According to a 2010 estimate by Johnson and Grim, Shaivism is the second-largest Hindu sect, constituting about 253 million or 26.6% of Hindus.

Hinduism in Southeast Asia had a profound impact on the region's cultural development and its history. As the Indic scripts were introduced from India, people of Southeast Asia entered the historical period by producing their earliest inscriptions around the 1st to 5th century CE. Today, Hindus in Southeast Asia are mainly Overseas Indians and Balinese. There are also Javanese and Balamon Cham minority in Cambodia and south central Vietnam who also practice Hinduism.

Jagannatha is a deity worshipped in regional Hindu traditions in India as part of a triad along with his brother Balabhadra, and sister, Subhadra. Jagannath, within Odia Hinduism, is the supreme god, Purushottama, and the Para Brahman. To most Vaishnava Hindus, particularly the Krishnaites, Jagannath is an abstract representation of Krishna, or Vishnu, sometimes as the avatar of Krishna or Vishnu. To some Shaiva and Shakta Hindus, he is a symmetry-filled tantric form of Bhairava, a fierce manifestation of Shiva associated with annihilation.

Hinduism is the Fourth-largest religion in Myanmar, being practised by 1.7% of the population of Myanmar. Hinduism is practised by about 890,000 people in Myanmar, and has been influenced by elements of Buddhism, with many Hindu temples in Myanmar housing statues of the Buddha. There are also a large population of Hindus in which the Myanmar Tamils and minority Bengali Hindus having the biggest population share.

The Smartatradition, also called Smartism, is a movement in Hinduism that developed and expanded with the Puranas genre of literature. It reflects a synthesis of four philosophical strands, namely Uttara Mīmāṃsā, Advaita, Yoga, and theism. The Smarta tradition rejects theistic sectarianism, and is notable for the domestic worship of five shrines with five deities, all treated as equal – Ganesha, Shiva, Shakti, Vishnu and Surya. The Smarta tradition contrasted with the older Shrauta tradition, which was based on elaborate rituals and rites. There has been a considerable overlap in the ideas and practices of the Smarta tradition with other significant historic movements within Hinduism, namely Shaivism, Brahmanism, Vaishnavism, and Shaktism.

The following list consists of notable concepts that are derived from Hindu culture and associated cultures’ traditions, which are expressed as words in Sanskrit or other Indic languages and Dravidian languages. The main purpose of this list is to disambiguate multiple spellings, to make note of spellings no longer in use for these concepts, to define the concept in one or two lines, to make it easy for one to find and pin down specific concepts, and to provide a guide to unique concepts of Hinduism all in one place.

Hinduism is a minority religion in Japan mainly followed by the Indian and Nepali expatriate residents of Japan, who number about 166,550 people as of 2022.

Hinduism in Mongolia is a minority religion; it has few followers and only began to appear in Mongolia in the late twentieth century. According to the 2010 and 2011 Mongolian census, the majority of people that identify as religious follow Buddhism (86%), Shamanism (4.7), Islam (4.9%) or Christianity (3.5). Only 0.5% of the population follow other religions.

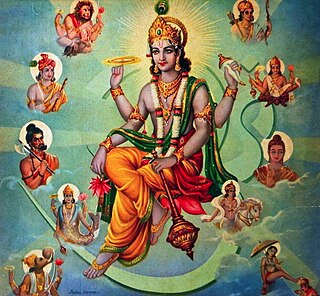

Vaishnavism is one of the major Hindu denominations along with Shaivism, Shaktism, and Smartism. It is also called Vishnuism since it considers Vishnu as the sole supreme being leading all other Hindu deities, that is, Mahavishnu. Its followers are called Vaishnavites or Vaishnavas, and it includes sub-sects like Krishnaism and Ramaism, which consider Krishna and Rama as the supreme beings respectively. According to a 2010 estimate by Johnson and Grim, Vaishnavism is the largest Hindu sect, constituting about 641 million or 67.6% of Hindus.

Vishnu, also known as Narayana and Hari, is one of the principal deities of Hinduism. He is the supreme being within Vaishnavism, one of the major traditions within contemporary Hinduism.

Devī is the Sanskrit word for 'goddess'; the masculine form is deva. Devi and deva mean 'heavenly, divine, anything of excellence', and are also gender-specific terms for a deity in Hinduism.

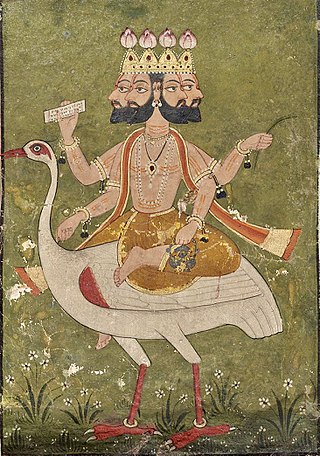

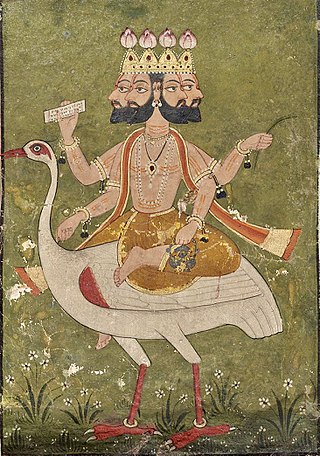

Brahma is a Hindu god, referred to as "the Creator" within the Trimurti, the trinity of supreme divinity that includes Vishnu and Shiva. He is associated with creation, knowledge, and the Vedas. Brahma is prominently mentioned in creation legends. In some Puranas, he created himself in a golden embryo known as the Hiranyagarbha.

Hindu denominations, sampradayas, traditions, movements, and sects are traditions and sub-traditions within Hinduism centered on one or more gods or goddesses, such as Vishnu, Shiva, Shakti and so on. The term sampradaya is used for branches with a particular founder-guru with a particular philosophy.

The Twenty-Four Protective Deities or the Twenty-Four Devas, sometimes reduced to the Twenty Protective Deities or the Twenty Devas, are a group of dharmapalas in Chinese Buddhism who are venerated as defenders of the Buddhist dharma. The group consists of devas, naga kings, vajra-holders and other beings, mostly borrowed from Hinduism with some borrowed from Taoism.