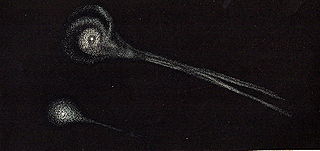

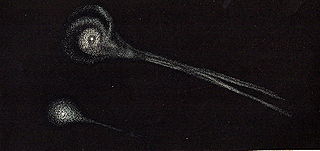

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that warms and begins to release gases when passing close to the Sun, a process called outgassing. This produces an extended, gravitationally unbound atmosphere or coma surrounding the nucleus, and sometimes a tail of gas and dust gas blown out from the coma. These phenomena are due to the effects of solar radiation and the outstreaming solar wind plasma acting upon the nucleus of the comet. Comet nuclei range from a few hundred meters to tens of kilometers across and are composed of loose collections of ice, dust, and small rocky particles. The coma may be up to 15 times Earth's diameter, while the tail may stretch beyond one astronomical unit. If sufficiently close and bright, a comet may be seen from Earth without the aid of a telescope and can subtend an arc of up to 30° across the sky. Comets have been observed and recorded since ancient times by many cultures and religions.

Comet Hale–Bopp is a comet that was one of the most widely observed of the 20th century and one of the brightest seen for many decades.

Astronomy is the oldest of the natural sciences, dating back to antiquity, with its origins in the religious, mythological, cosmological, calendrical, and astrological beliefs and practices of prehistory: vestiges of these are still found in astrology, a discipline long interwoven with public and governmental astronomy. It was not completely separated in Europe during the Copernican Revolution starting in 1543. In some cultures, astronomical data was used for astrological prognostication.

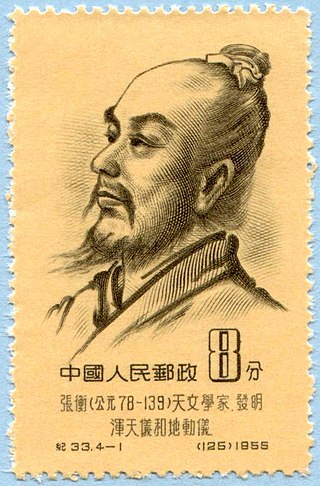

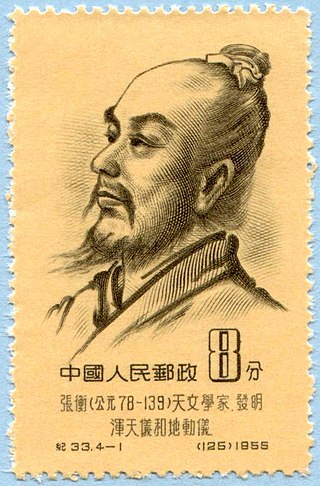

Zhang Heng, formerly romanized as Chang Heng, was a Chinese polymathic scientist and statesman who lived during the Han dynasty. Educated in the capital cities of Luoyang and Chang'an, he achieved success as an astronomer, mathematician, seismologist, hydraulic engineer, inventor, geographer, cartographer, ethnographer, artist, poet, philosopher, politician, and literary scholar.

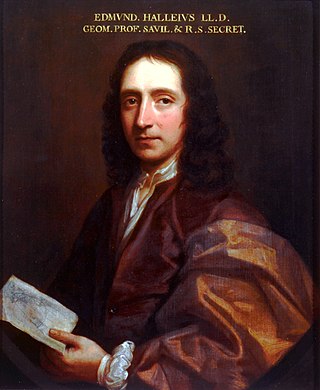

Halley's Comet, Comet Halley, or sometimes simply Halley, officially designated 1P/Halley, is a short-period comet visible from Earth every 75–79 years. Halley is the only known short-period comet that is regularly visible to the naked eye from Earth, and thus the only naked-eye comet that can appear twice in a human lifetime. It last appeared in the inner parts of the Solar System in 1986 and will next appear in mid-2061.

12P/Pons–Brooks is a periodic comet with an orbital period of 71 years. It fits the classical definition of a Halley-type comet with, and is also one of the brightest known periodic comets, reaching an absolute visual magnitude ~5 in its approach to perihelion. Comet Pons-Brooks was discovered at Marseilles Observatory in July 1812 by Jean-Louis Pons, and then later recovered in 1883 by William Robert Brooks.

Biela's Comet or Comet Biela was a periodic Jupiter-family comet first recorded in 1772 by Montaigne and Messier and finally identified as periodic in 1826 by Wilhelm von Biela. It was subsequently observed to split in two and has not been seen since 1852. As a result, it is currently considered to have been destroyed, although remnants appeared to have survived for some time as a meteor shower, the Andromedids.

Astronomy in China has a long history stretching from the Shang dynasty, being refined over a period of more than 3,000 years. The ancient Chinese people have identified stars from 1300 BCE, as Chinese star names later categorized in the twenty-eight mansions have been found on oracle bones unearthed at Anyang, dating back to the mid-Shang dynasty. The core of the "mansion" system also took shape around this period, by the time of King Wu Ding.

The Kreutz sungrazers are a family of sungrazing comets, characterized by orbits taking them extremely close to the Sun at perihelion. They are believed to be fragments of one large comet that broke up several centuries ago and are named for German astronomer Heinrich Kreutz, who first demonstrated that they were related. A Kreutz sungrazer's aphelion is about 170 AU from the Sun; these sungrazers make their way from the distant outer Solar System from a patch in the sky in Canis Major, to the inner Solar System, to their perihelion point near the Sun, and then leave the inner Solar System in their return trip to their aphelion.

F. Richard Stephenson is an Emeritus Professor at the University of Durham, in the Physics department and the East Asian Studies department. His research concentrates on historical aspects of astronomy, in particular analyzing ancient astronomical records to reconstruct the history of Earth's rotation. He has an asteroid named after him: 10979 Fristephenson.

Historical astronomy is the science of analysing historic astronomical data. The American Astronomical Society (AAS), established 1899, states that its Historical Astronomy Division "...shall exist for the purpose of advancing interest in topics relating to the historical nature of astronomy. By historical astronomy we include the history of astronomy; what has come to be known as archaeoastronomy; and the application of historical records to modern astrophysical problems." Historical and ancient observations are used to track theoretically long term trends, such as eclipse patterns and the velocity of nebular clouds. Conversely, utilizing known and well documented phenomenological activity, historical astronomers apply computer models to verify the validity of ancient observations, as well as dating such observations and documents which would otherwise be unknown.

In Chinese astronomy, a guest star is a star which has suddenly appeared in a place where no star had previously been observed and becomes invisible again after some time. The term is a literal translation from ancient Chinese astronomical records.

D/1770 L1, popularly known as Lexell's Comet after its orbit computer Anders Johan Lexell, was a comet discovered by astronomer Charles Messier in June 1770. It is notable for having passed closer to Earth than any other comet in recorded history, approaching to a distance of only 0.015 astronomical units, or six times the distance from the Earth to the Moon. The comet has not been seen since 1770 and is considered a lost comet.

122P/de Vico is a periodic comet with an orbital period of 74 years. It fits the classical definition of a Halley-type comet with. It was discovered by Francesco de Vico in Rome on February 20, 1846.

Caesar's Comet was a seven-day cometary outburst seen in July 44 BC. It was interpreted by Romans as a sign of the deification of recently assassinated dictator, Julius Caesar. It was perhaps the most famous comet of antiquity.

Comet Swift–Tuttle is a large periodic comet with a 1995 (osculating) orbital period of 133 years that is in a 1:11 orbital resonance with Jupiter. It fits the classical definition of a Halley-type comet, which has an orbital period between 20 and 200 years. The comet was independently discovered by Lewis Swift on July 16, 1862 and by Horace Parnell Tuttle on July 19, 1862.

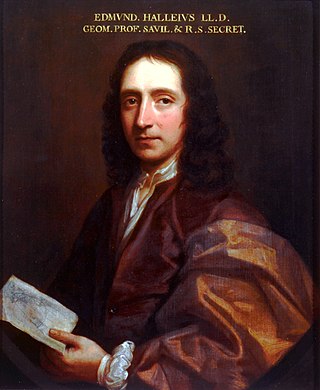

EdmondHalley was an English astronomer, mathematician and physicist. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

Comets have been observed by humanity for thousands of years, but only in the past few centuries have they been studied as astronomical phenomena. Before modern times, great comets caused worldwide fear, considered bad omens foreboding disaster and turmoil, for example the 1066 passage of Halley's Comet depicted as heralding the Norman conquest of England. As the science of astronomy developed planetary theories, understanding the nature and composition of comets became a challenging mystery and a large area of study.

A great comet is a comet that becomes exceptionally bright. There is no official definition; often the term is attached to comets such as Halley's Comet, which during certain appearances are bright enough to be noticed by casual observers who are not looking for them, and become well known outside the astronomical community. Great comets appear at irregular, unpredictable intervals, on average about once per decade. Although comets are officially named after their discoverers, great comets are sometimes also referred to by the year in which they appeared great, using the formulation "The Great Comet of ...", followed by the year.