To be born again, or to experience the new birth, is a phrase, particularly in evangelicalism, that refers to a "spiritual rebirth", or a regeneration of the human spirit. In contrast to one's physical birth, being "born again" is distinctly and separately caused by the operation of the Holy Spirit, and it occurs when one surrenders their life to Christ. It is a core doctrine of the denominations of the Anabaptist, Moravian, Methodist, Baptist, Plymouth Brethren and Pentecostal Churches along with all other evangelical Christian denominations. All of these Churches strongly believe Jesus's words in the Gospels: "You must be born again before you can see, or enter, the Kingdom of Heaven". Their doctrines also mandate that to be both "born again" and "saved", one must have a personal and intimate relationship with Jesus Christ.

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.4 billion followers, comprising around 31.2% of the world population. Its adherents, known as Christians, are estimated to make up a majority of the population in 157 countries and territories. Christians believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, whose coming as the Messiah was prophesied in the Hebrew Bible and chronicled in the New Testament.

John Shelby "Jack" Spong was an American bishop of the Episcopal Church, born in Charlotte, North Carolina. He served as the Bishop of Newark, New Jersey from 1979 to 2000. Spong was a liberal Christian theologian, religion commentator, and author who called for a fundamental rethinking of Christian belief away from theism and traditional doctrines. He was known for his progressive and controversial views on Christianity, including his rejection of traditional Christian doctrines, his advocacy for LGBTQ rights, and his support for interfaith dialogue. Spong was a contributor to the Living the Questions DVD program and was a guest on numerous national television broadcasts. Spong died on September 12, 2021, at his home in Richmond, Virginia, at the age of 90.

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. Elements of the sermon often include exposition, exhortation, and practical application. The act of delivering a sermon is called preaching. In secular usage, the word sermon may refer, often disparagingly, to a lecture on morals.

In Christian eschatology, postmillennialism, or postmillenarianism, is an interpretation of chapter 20 of the Book of Revelation which sees Christ's second coming as occurring after the "Millennium", a messianic age in which Christian ethics prosper. The term subsumes several similar views of the end times, and it stands in contrast to premillennialism and, to a lesser extent, amillennialism.

According to Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God as chronicled in the Bible's New Testament, and in most Christian denominations He is held to be God the Son, a prosopon (Person) of the Trinity of God.

The Boyle Lectures are named after Robert Boyle, a prominent natural philosopher of the 17th century and son of Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork. Under the terms of his Will, Robert Boyle endowed a series of lectures or sermons which were to consider the relationship between Christianity and the new natural philosophy then emerging in European society. Since 2004, this prestigious Lectures series has been organized, with the assistance of Board of the Boyle Lectures, by the International Society for Science and Religion (ISSR) and has been held at one of its original locations, the Wren church of St Mary-le-Bow on Cheapside in the City of London.

Liberal Christianity, also known as liberal theology and historically as Christian Modernism, is a movement that interprets Christian teaching by taking into consideration modern knowledge, science and ethics. It emphasizes the importance of reason and experience over doctrinal authority. Liberal Christians view their theology as an alternative to both atheistic rationalism and theologies based on traditional interpretations of external authority, such as the Bible or sacred tradition.

Postliberal theology is a Christian theological movement that focuses on a narrative presentation of the Christian faith as regulative for the development of a coherent systematic theology. Thus, Christianity is an overarching story, with its own embedded culture, grammar, and practices, which can be understood only with reference to Christianity's own internal logic.

Edmund Prosper Clowney was an American theologian, educator, and pastor.

Ed Parish Sanders was an American New Testament scholar and a principal proponent of the "New Perspective on Paul". He was a major scholar in the scholarship on the historical Jesus and contributed to the view that Jesus was part of a renewal movement within Judaism. Sanders identified himself as a "liberal, modern, secularized Protestant" in his book Jesus and Judaism; fellow scholar John P. Meier called him a postliberal Protestant. He was Arts and Sciences Professor of Religion at Duke University, North Carolina from 1990 until his retirement in 2005.

The Bampton Lectures at the University of Oxford, England, were founded by a bequest of John Bampton. They have taken place since 1780.

Reverend Robert Taylor, was an early 19th-century Radical, a clergyman turned freethinker. His "Infidel home missionary tour" was an incident in Charles Darwin's education, leaving Darwin with a memory of "the Devil's Chaplain" as a warning of the dangers of dissent from Church of England doctrine.

In Protestant Christianity, the relationship between Law and Gospel—God's Law and the Gospel of Jesus Christ—is a major topic in Lutheran and Reformed theology. In these religious traditions, the distinction between the doctrines of Law, which demands obedience to God's ethical will, and Gospel, which promises the forgiveness of sins in light of the person and work of Jesus Christ, is critical. Ministers use it as a hermeneutical principle of biblical interpretation and as a guiding principle in homiletics and pastoral care. It involves the supersession of the Old Covenant by the New Covenant and Christian theology.

Keith Ward is an English philosopher and theologian. He is a fellow of the British Academy and a priest of the Church of England. He was a canon of Christ Church, Oxford, until 2003. Comparative theology and the relationship between science and religion are two of his main topics of interest.

Charles Harold Dodd was a Welsh New Testament scholar and influential Protestant theologian. He is known for promoting "realized eschatology", the belief that Jesus' references to the kingdom of God meant a present reality rather than a future apocalypse. He was influenced by Martin Heidegger and Rudolf Otto.

This is a glossary of terms used in Christianity.

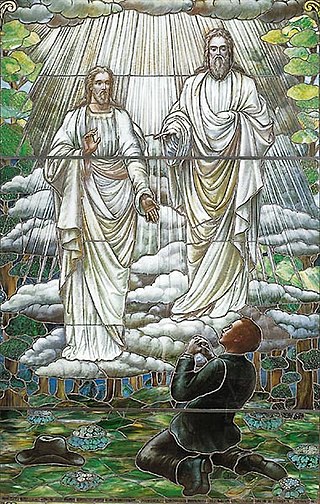

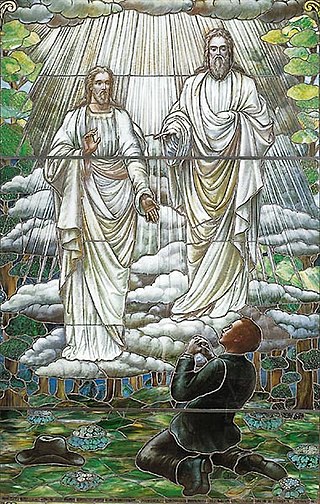

Mormonism and Nicene Christianity have a complex theological, historical, and sociological relationship. Mormons express their doctrines using biblical terminology. They have similar views about the nature of Jesus Christ's atonement, bodily resurrection, and Second Coming as mainstream Christians. Nevertheless, most Mormons do not accept the doctrine of the Trinity as codified in the Nicene Creed of 325 and the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed of 381. Although Mormons consider the Protestant Bible to be holy scripture, they do not believe in biblical inerrancy. They have also adopted additional scriptures that they believe to have been divinely revealed to Joseph Smith, including the Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price. Mormons practice baptism and celebrate the sacrament of the Lord's Supper, but they also participate in other religious rituals. Mormons self-identify as Christians.

William David Davies (1911–2001), often cited as W. D. Davies, was a Welsh Congregationalist minister, theologian, author and professor of religion in England and the United States.

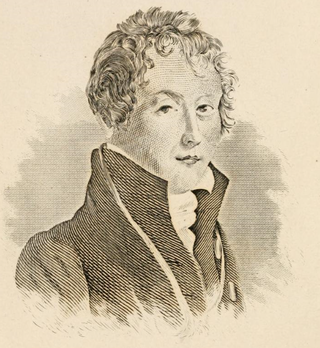

Christopher Benson (1788–1868) was an English theologian who achieved prominence on account of his abilities as a preacher and lecturer. In 1820 he was chosen as the first Hulsean Lecturer. Later he was one of the first to apply the term Tractarians to John Keble, Edward Pusey, and other pioneers of what came to be known as the Oxford Movement within the Church of England. Christopher Benson was not a supporter, and engaged in high-profile theological controversies on matters such as the "apostolical authority of the Fathers".