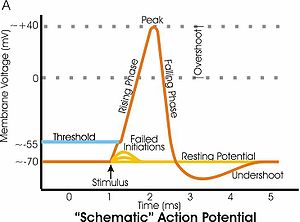

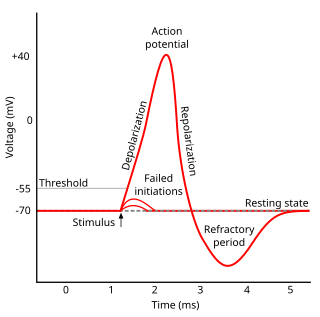

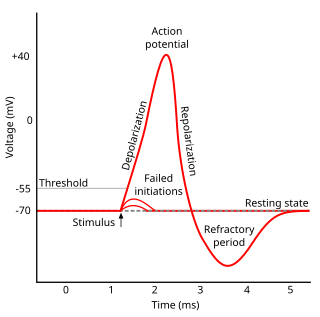

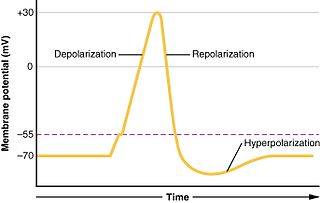

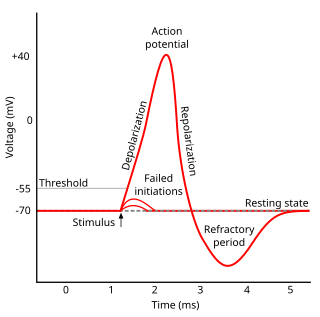

An action potential occurs when the membrane potential of a specific cell location rapidly rises and falls. This depolarization then causes adjacent locations to similarly depolarize. Action potentials occur in several types of animal cells, called excitable cells, which include neurons, muscle cells, and in some plant cells. Certain endocrine cells such as pancreatic beta cells, and certain cells of the anterior pituitary gland are also excitable cells.

Refractoriness is the fundamental property of any object of autowave nature not to respond on stimuli, if the object stays in the specific refractory state. In common sense, refractory period is the characteristic recovery time, a period that is associated with the motion of the image point on the left branch of the isocline .

In electrocardiography, the ventricular cardiomyocyte membrane potential is about −90 mV at rest, which is close to the potassium reversal potential. When an action potential is generated, the membrane potential rises above this level in four distinct phases.

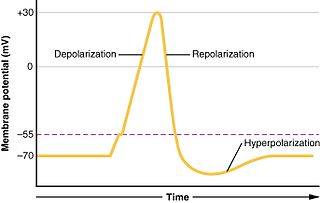

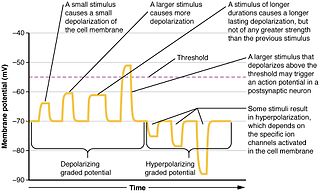

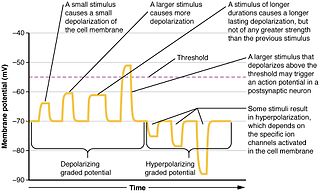

An inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP) is a kind of synaptic potential that makes a postsynaptic neuron less likely to generate an action potential. IPSP were first investigated in motorneurons by David P. C. Lloyd, John Eccles and Rodolfo Llinás in the 1950s and 1960s. The opposite of an inhibitory postsynaptic potential is an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP), which is a synaptic potential that makes a postsynaptic neuron more likely to generate an action potential. IPSPs can take place at all chemical synapses, which use the secretion of neurotransmitters to create cell to cell signalling. Inhibitory presynaptic neurons release neurotransmitters that then bind to the postsynaptic receptors; this induces a change in the permeability of the postsynaptic neuronal membrane to particular ions. An electric current that changes the postsynaptic membrane potential to create a more negative postsynaptic potential is generated, i.e. the postsynaptic membrane potential becomes more negative than the resting membrane potential, and this is called hyperpolarisation. To generate an action potential, the postsynaptic membrane must depolarize—the membrane potential must reach a voltage threshold more positive than the resting membrane potential. Therefore, hyperpolarisation of the postsynaptic membrane makes it less likely for depolarisation to sufficiently occur to generate an action potential in the postsynaptic neurone.

In biology, depolarization or hypopolarization is a change within a cell, during which the cell undergoes a shift in electric charge distribution, resulting in less negative charge inside the cell compared to the outside. Depolarization is essential to the function of many cells, communication between cells, and the overall physiology of an organism.

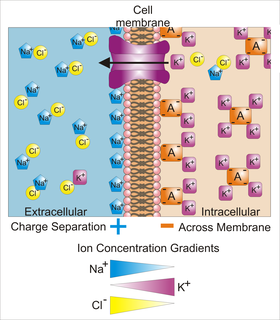

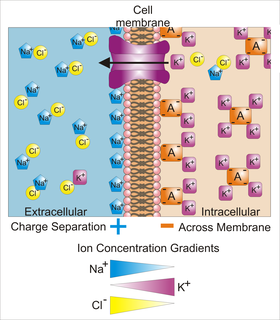

Membrane potential is the difference in electric potential between the interior and the exterior of a biological cell. That is, there is a difference in the energy required for electric charges to move from the internal to exterior cellular environments and vice versa, as long as there is no acquisition of kinetic energy or the production of radiation. The concentration gradients of the charges directly determine this energy requirement. For the exterior of the cell, typical values of membrane potential, normally given in units of millivolts and denoted as mV, range from –80 mV to –40 mV.

Graded potentials are changes in membrane potential that vary in size, as opposed to being all-or-none. They include diverse potentials such as receptor potentials, electrotonic potentials, subthreshold membrane potential oscillations, slow-wave potential, pacemaker potentials, and synaptic potentials, which scale with the magnitude of the stimulus. They arise from the summation of the individual actions of ligand-gated ion channel proteins, and decrease over time and space. They do not typically involve voltage-gated sodium and potassium channels. These impulses are incremental and may be excitatory or inhibitory. They occur at the postsynaptic dendrite in response to presynaptic neuron firing and release of neurotransmitter, or may occur in skeletal, smooth, or cardiac muscle in response to nerve input. The magnitude of a graded potential is determined by the strength of the stimulus.

In electrophysiology, the threshold potential is the critical level to which a membrane potential must be depolarized to initiate an action potential. In neuroscience, threshold potentials are necessary to regulate and propagate signaling in both the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS).

The axon hillock is a specialized part of the cell body of a neuron that connects to the axon. It can be identified using light microscopy from its appearance and location in a neuron and from its sparse distribution of Nissl substance.

The cardiac action potential is a brief change in voltage across the cell membrane of heart cells. This is caused by the movement of charged atoms between the inside and outside of the cell, through proteins called ion channels. The cardiac action potential differs from action potentials found in other types of electrically excitable cells, such as nerves. Action potentials also vary within the heart; this is due to the presence of different ion channels in different cells.

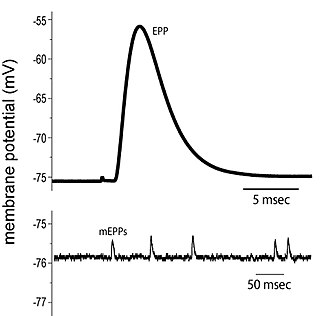

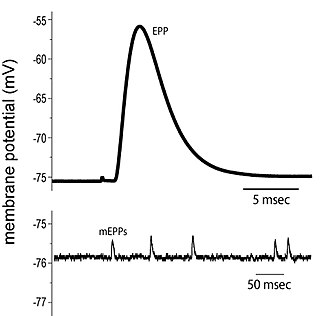

End plate potentials (EPPs) are the voltages which cause depolarization of skeletal muscle fibers caused by neurotransmitters binding to the postsynaptic membrane in the neuromuscular junction. They are called "end plates" because the postsynaptic terminals of muscle fibers have a large, saucer-like appearance. When an action potential reaches the axon terminal of a motor neuron, vesicles carrying neurotransmitters are exocytosed and the contents are released into the neuromuscular junction. These neurotransmitters bind to receptors on the postsynaptic membrane and lead to its depolarization. In the absence of an action potential, acetylcholine vesicles spontaneously leak into the neuromuscular junction and cause very small depolarizations in the postsynaptic membrane. This small response (~0.4mV) is called a miniature end plate potential (MEPP) and is generated by one acetylcholine-containing vesicle. It represents the smallest possible depolarization which can be induced in a muscle.

In neuroscience, repolarization refers to the change in membrane potential that returns it to a negative value just after the depolarization phase of an action potential which has changed the membrane potential to a positive value. The repolarization phase usually returns the membrane potential back to the resting membrane potential. The efflux of potassium (K+) ions results in the falling phase of an action potential. The ions pass through the selectivity filter of the K+ channel pore.

The induction of NMDA receptor-dependent long-term potentiation (LTP) in chemical synapses in the brain occurs via a fairly straightforward mechanism. A substantial and rapid rise in calcium ion concentration inside the postsynaptic cell is most possibly all that is required to induce LTP. But the mechanism of calcium delivery to the postsynaptic cell in inducing LTP is more complicated.

In neuroscience, the axolemma is the cell membrane of an axon, the branch of a neuron through which signals are transmitted. The axolemma is a three-layered, bilipid membrane. Under standard electron microscope preparations, the structure is approximately 8 nanometers thick.

Sodium channels are integral membrane proteins that form ion channels, conducting sodium ions (Na+) through a cell's membrane. They belong to the superfamily of cation channels and can be classified according to the trigger that opens the channel for such ions, i.e. either a voltage-change ("voltage-gated", "voltage-sensitive", or "voltage-dependent" sodium channel; also called "VGSCs" or "Nav channel") or a binding of a substance (a ligand) to the channel (ligand-gated sodium channels).

Afterhyperpolarization, or AHP, is the hyperpolarizing phase of a neuron's action potential where the cell's membrane potential falls below the normal resting potential. This is also commonly referred to as an action potential's undershoot phase. AHPs have been segregated into "fast", "medium", and "slow" components that appear to have distinct ionic mechanisms and durations. While fast and medium AHPs can be generated by single action potentials, slow AHPs generally develop only during trains of multiple action potentials.

Low-threshold spikes (LTS) refer to membrane depolarizations by the T-type calcium channel. LTS occur at low, negative, membrane depolarizations. They often follow a membrane hyperpolarization, which can be the result of decreased excitability or increased inhibition. LTS result in the neuron reaching the threshold for an action potential. LTS is a large depolarization due to an increase in Ca2+ conductance, so LTS is mediated by calcium (Ca2+) conductance. The spike is typically crowned by a burst of two to seven action potentials, which is known as a low-threshold burst. LTS are voltage dependent and are inactivated if the cell's resting membrane potential is more depolarized than −60mV. LTS are deinactivated, or recover from inactivation, if the cell is hyperpolarized and can be activated by depolarizing inputs, such as excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSP). LTS were discovered by Rodolfo Llinás and coworkers in the 1980s.

In neurophysiology, a dendritic spike refers to an action potential generated in the dendrite of a neuron. Dendrites are branched extensions of a neuron. They receive electrical signals emitted from projecting neurons and transfer these signals to the cell body, or soma. Dendritic signaling has traditionally been viewed as a passive mode of electrical signaling. Unlike its axon counterpart which can generate signals through action potentials, dendrites were believed to only have the ability to propagate electrical signals by physical means: changes in conductance, length, cross sectional area, etc. However, the existence of dendritic spikes was proposed and demonstrated by W. Alden Spencer, Eric Kandel, Rodolfo Llinás and coworkers in the 1960s and a large body of evidence now makes it clear that dendrites are active neuronal structures. Dendrites contain voltage-gated ion channels giving them the ability to generate action potentials. Dendritic spikes have been recorded in numerous types of neurons in the brain and are thought to have great implications in neuronal communication, memory, and learning. They are one of the major factors in long-term potentiation.

Cellular neuroscience is a branch of neuroscience concerned with the study of neurons at a cellular level. This includes morphology and physiological properties of single neurons. Several techniques such as intracellular recording, patch-clamp, and voltage-clamp technique, pharmacology, confocal imaging, molecular biology, two photon laser scanning microscopy and Ca2+ imaging have been used to study activity at the cellular level. Cellular neuroscience examines the various types of neurons, the functions of different neurons, the influence of neurons upon each other, and how neurons work together.

A depolarizing prepulse (DPP) is an electrical stimulus that causes the potential difference measured across a neuronal membrane to become more positive or less negative, and precedes another electrical stimulus. DPPs may be of either the voltage or current stimulus variety and have been used to inhibit neural activity, selectively excite neurons, and increase the pain threshold associated with electrocutaneous stimulation.