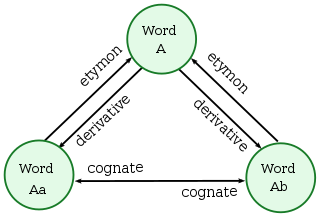

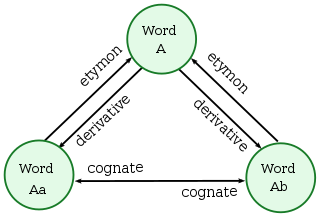

In linguistics, cognates, also called lexical cognates, are words that have a common etymological origin. Cognates are often inherited from a shared parent language, but they may also involve borrowings from some other language. For example, the English words dish, disk and desk, the German word Tisch ("table"), and the Latin word discus ("disk") are cognates because they all come from Ancient Greek δίσκος, which relates to their flat surfaces. Cognates may have evolved similar, different or even opposite meanings, and although there are usually some similar sounds or letters in the words, they may appear to be dissimilar. Some words sound similar, but do not come from the same root; these are called false cognates, while some are truly cognate but differ in meaning; these are called false friends.

Danish is a North Germanic language spoken by about six million people, principally in Denmark, Greenland, the Faroe Islands and in the region of Southern Schleswig in northern Germany, where it has minority language status. Also, minor Danish-speaking communities are found in Norway, Sweden, the United States, Canada, Brazil, and Argentina. Due to immigration from Denmark, about 10% of the population of Greenland speak Danish as their first language.

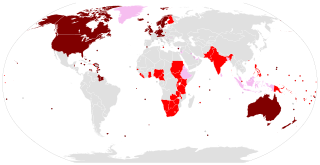

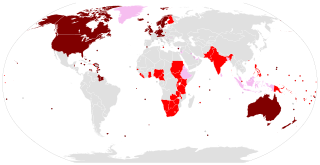

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family spoken natively by a population of about 515 million people mainly in Europe, North America, Oceania and Southern Africa. The most widely spoken Germanic language, English, is also the world's most widely spoken language with an estimated 2 billion speakers. All Germanic languages are derived from Proto-Germanic, spoken in Iron Age Scandinavia.

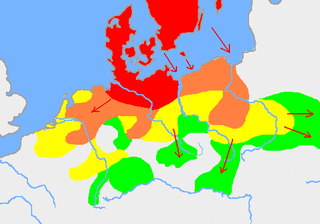

Norwegian is a North Germanic language spoken mainly in Norway, where it is an official language. Along with Swedish and Danish, Norwegian forms a dialect continuum of more or less mutually intelligible local and regional varieties; some Norwegian and Swedish dialects, in particular, are very close. These Scandinavian languages, together with Faroese and Icelandic as well as some extinct languages, constitute the North Germanic languages. Faroese and Icelandic are not mutually intelligible with Norwegian in their spoken form because continental Scandinavian has diverged from them. While the two Germanic languages with the greatest numbers of speakers, English and German, have close similarities with Norwegian, neither is mutually intelligible with it. Norwegian is a descendant of Old Norse, the common language of the Germanic peoples living in Scandinavia during the Viking Age.

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlements and chronologically coincides with the Viking Age, the Christianization of Scandinavia and the consolidation of Scandinavian kingdoms from around the 7th to the 15th centuries.

Swedish is a North Germanic language spoken natively by at least 10 million people, predominantly in Sweden and in parts of Finland, where it has equal legal standing with Finnish. It is largely mutually intelligible with Norwegian and Danish, although the degree of mutual intelligibility is largely dependent on the dialect and accent of the speaker. Written Norwegian and Danish are usually more easily understood by Swedish speakers than the spoken languages, due to the differences in tone, accent, and intonation. Swedish is a descendant of Old Norse, the common language of the Germanic peoples living in Scandinavia during the Viking Era. It has more speakers than any other North Germanic language.

A loanword is a word as permanently adopted from one language and incorporated into another language without translation. This is in contrast to cognates, which are words in two or more languages that are similar because they share an etymological origin, and calques, which involve translation. Loanwords from languages with different scripts are usually transliterated, but they are not translated.

In linguistics, a calque or loan translation is a word or phrase borrowed from another language by literal word-for-word or root-for-root translation. When used as a verb, "to calque" means to borrow a word or phrase from another language while translating its components, so as to create a new lexeme in the target language. For instance, the English word "skyscraper" led to calques in dozens of other languages. Another notable example is the Latin weekday names, which came to be associated by ancient Germanic speakers with their own gods following a practice known as interpretatio germanica: the Latin "Day of Mercury", Mercurii dies, was borrowed into Late Proto-Germanic as the "Day of Wōđanaz" (*Wodanesdag), which became Wōdnesdæg in Old English, then "Wednesday" in Modern English.

The Greek language has contributed to the English vocabulary in five main ways:

Gairaigo is Japanese for "loan word", and indicates a transcription into Japanese. In particular, the word usually refers to a Japanese word of foreign origin that was not borrowed in ancient times from Old or Middle Chinese, but in modern times, primarily from English, Portuguese, Dutch, and modern Chinese dialects, such as Standard Chinese and Cantonese. These are primarily written in the katakana phonetic script, with a few older terms written in Chinese characters (kanji); the latter are known as ateji.

Phono-semantic matching (PSM) is the incorporation of a word into one language from another, often creating a neologism, where the word's non-native quality is hidden by replacing it with phonetically and semantically similar words or roots from the adopting language. Thus, the approximate sound and meaning of the original expression in the source language are preserved, though the new expression in the target language may sound native.

English is a Germanic language but has Latin influences, with a grammar and a core vocabulary inherited from Proto-Germanic. However, a significant portion of the English vocabulary comes from Romance and Latinate sources. A portion of these borrowings come directly from Latin, or through one of the Romance languages, particularly Anglo-Norman and French, but some also from Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish; or from other languages into Latin and then into English. The influence of Latin in English, therefore, is primarily lexical in nature, being confined mainly to words derived from Latin and Greek roots.

The replacing of loanwords in Turkish is part of a policy of Turkification of Atatürk. The Ottoman Turkish language had many loanwords from Arabic and Persian, but also European languages such as French, Greek, and Italian origin—which were officially replaced with their Turkish counterparts suggested by the Turkish Language Association as a part of the cultural reforms—in the broader framework of Atatürk's Reforms—following the foundation of the Republic of Turkey.

Many words that existed in Old English did not survive into Modern English. There are also many words in Modern English that bear little or no resemblance in meaning to their Old English etymons. Some linguists estimate that as much as 80 percent of the lexicon of Old English was lost by the end of the Middle English period, including many compound words, e.g. bōchūs, yet the components 'book' and 'house' were kept. Certain categories of words seem to have been more susceptible. Nearly all words relating to sexual intercourse and sexual organs as well as "impolite" words for bodily functions were ignored in favor of words borrowed from Latin or Ancient Greek. The Old English synonyms are now mostly either extinct or considered crude or vulgar, such as arse/ass.

The languages of Scotland are the languages spoken or once spoken in Scotland. Each of the numerous languages spoken in Scotland during its recorded linguistic history falls into either the Germanic or Celtic language families. The classification of the Pictish language was once controversial, but it is now generally considered a Celtic language. Today, the main language spoken in Scotland is English, while Scots and Scottish Gaelic are minority languages. The dialect of English spoken in Scotland is referred to as Scottish English.

Linguistic purism in Icelandic is the policy of discouraging new loanwords from entering the language, by creating new words from Old Icelandic and Old Norse roots. In Iceland, linguistic purism is archaising, trying to resuscitate the language of a golden age of Icelandic literature. The effort began in the early 19th century, at the dawn of the Icelandic national movement, aiming at replacing older loanwords, especially from Danish, and it continues today, targeting English words. It is widely upheld in Iceland and it is the dominant language ideology. It is fully supported by the Icelandic government through the Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies, the Icelandic Language Council, the Icelandic Language Fund and an Icelandic Language Day.

The history of the Icelandic language began in the 9th century when the settlement of Iceland, mostly by Norwegians, brought a dialect of Old Norse to the island.

Gothic is an extinct East Germanic language that was spoken by the Goths. It is known primarily from the Codex Argenteus, a 6th-century copy of a 4th-century Bible translation, and is the only East Germanic language with a sizeable text corpus. All others, including Burgundian and Vandalic, are known, if at all, only from proper names that survived in historical accounts, and from loanwords in other languages such as Portuguese, Spanish, and French.

Icelandic is a North Germanic language spoken by about 314,000 people, the vast majority of whom live in Iceland where it is the national language. As a West Scandinavian language, it is most closely related to Faroese, extinct Norn, and western Norwegian dialects.