Giulio Cesare was one of three Conte di Cavour-class dreadnought battleships built for the Royal Italian Navy in the 1910s. Completed in 1914, she was little used and saw no combat during the First World War. The ship supported operations during the Corfu Incident in 1923 and spent much of the rest of the decade in reserve. She was rebuilt between 1933 and 1937 with more powerful guns, additional armor and considerably more speed than before.

The Zara class was a group of four heavy cruisers built for the Italian Regia Marina in the late 1920s and the early 1930s. The class comprised the vessels Zara, Fiume, Gorizia, and Pola, the last of which was completed to a slightly different design. The ships were a substantial improvement over the preceding Trento-class cruisers, incorporating significantly heavier armor protection at the cost of the very high speed of the Trentos. They carried the same main battery of eight 203 mm (8.0 in) guns and had a maximum speed of 32 knots. Among the best-protected heavy cruisers built by any navy in the 1930s, the heavy armor was acquired only by violating the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty, which limited cruiser displacement to 10,000 long tons (10,160 t).

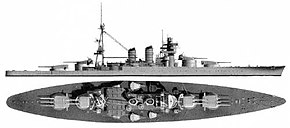

The Conte di Cavour–class battleships were a group of three dreadnoughts built for the Royal Italian Navy in the 1910s. The ships were completed during World War I, but none saw action before the end of hostilities. Leonardo da Vinci was sunk by a magazine explosion in 1916 and sold for scrap in 1923. The two surviving ships, Conte di Cavour and Giulio Cesare, supported operations during the Corfu Incident in 1923. They were extensively reconstructed between 1933 and 1937 with more powerful guns, additional armor and considerably more speed than before.

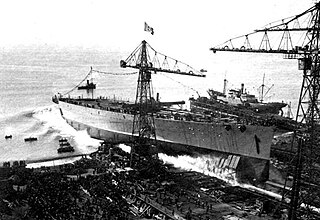

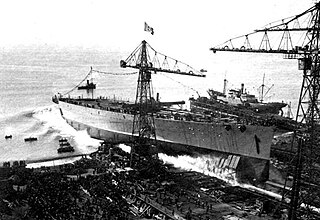

Aquila was an Italian aircraft carrier converted from the transatlantic passenger liner SS Roma. During World War II, Work on Aquila began in late 1941 at the Ansaldo shipyard in Genoa and continued for the next two years. With the signing of the Italian armistice on 8 September 1943, however, all work was halted and the vessel remained unfinished. She was captured by the National Republican Navy of the Italian Social Republic and the German occupation forces in 1943, but in 1945 she was partially sunk by a commando attack of Mariassalto, an Italian royalist assault unit of the Co-Belligerent Navy of the Kingdom of Italy, made up by members of the former Decima Flottiglia MAS. Aquila was eventually refloated and scrapped in 1952.

Littorio was the lead ship of her class of battleship; she served in the Italian Regia Marina during World War II. She was named after the Lictor, in ancient times the bearer of the Roman fasces, which was adopted as the symbol of Italian Fascism. Littorio and her sister Vittorio Veneto were built in response to the French battleships Dunkerque and Strasbourg. They were Italy's first modern battleships, and the first 35,000-ton capital ships of any nation to be laid down under the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty. Littorio was laid down in October 1934, launched in August 1937, and completed in May 1940.

Duilio was an Italian Andrea Doria-class battleship that served in the Regia Marina during World War I and World War II. She was named after the Roman fleet commander Gaius Duilius. Duilio was laid down in February 1912, launched in April 1913, and completed in May 1916. She was initially armed with a main battery of thirteen 305 mm (12.0 in) guns, but a major reconstruction in the late 1930s replaced these with ten 320 mm (13 in) guns. Duilio saw no action during World War I owing to the inactivity of the Austro-Hungarian fleet during the conflict. She cruised the Mediterranean in the 1920s and was involved in the Corfu incident in 1923.

The Littorio class, also known as the Vittorio Veneto class, was a class of battleship of the Regia Marina, the Italian navy. The class was composed of four ships—Littorio, Vittorio Veneto, Roma, and Impero—but only the first three ships of the class were completed. Built between 1934 and 1942, they were the most modern battleships used by Italy during World War II. They were developed in response to the French Dunkerque-class battleships, and were armed with 381-millimeter (15.0 in) guns and had a top speed of 30 knots. The class's design was considered by the Spanish Navy, but the outbreak of World War II interrupted construction plans.

Leonardo da Vinci was the last of three Conte di Cavour-class dreadnoughts built for the Regia Marina in the early 1910s. Completed just before the beginning of World War I, the ship saw no action and was sunk by a magazine explosion in 1916 with the loss of 248 officers and enlisted men. The Italians blamed Austro-Hungarian saboteurs for her loss, but it may have been accidental. Leonardo da Vinci was refloated in 1919 and plans were made to repair her. Budgetary constraints did not permit this, and her hulk was sold for scrap in 1923.

The Imperatritsa Mariya-class battleships were the first dreadnoughts built for the Black Sea Fleet of the Imperial Russian Navy. All three ships were built in Nikolayev during World War I; two of the ships were built by the Rossud Dockyard and the third was built by the Associated Factories and Shipyards of Nikolayev. Two ships were delivered in 1915 and saw some combat against ex-German warships that had been 'gifted' to the Ottoman Empire, but the third was not completed until 1917 and saw no combat due to the disorder in the navy after the February Revolution earlier that year.

The Normandie class consisted of five dreadnought battleships ordered for the French Navy in 1912–1913. It comprised Normandie, the lead ship, Flandre, Gascogne, Languedoc, and Béarn. The design incorporated a radical arrangement for the twelve 340 mm (13.4 in) main battery guns: three quadruple-gun turrets, the first of their kind, as opposed to the twin-gun turrets used by most other navies. The first four ships were also equipped with an unusual hybrid propulsion system that used both steam turbines and triple-expansion steam engines to increase fuel efficiency.

The Andrea Doria class was a pair of dreadnought battleships built for the Royal Italian Navy between 1912 and 1916. The two ships—Andrea Doria and Duilio—were completed during World War I. The class was an incremental improvement over the preceding Conte di Cavour class. Like the earlier ships, Andrea Doria and Duilio were armed with a main battery of thirteen 305-millimeter (12.0 in) guns.

Dante Alighieri was the first dreadnought battleship built for the Regia Marina and was completed in 1913. The ship served as a flagship during World War I, but saw very little action other than the Second Battle of Durazzo in 1918 during which she did not engage enemy forces. She never fired her guns in anger during her career. Dante Alighieri was refitted in 1923, stricken from the Navy List five years later and subsequently sold for scrap.

Impero was the fourth Littorio-class battleship built for Italy's Regia Marina during the Second World War. She was named after the Italian word for "empire", in this case referring to the newly (1936) conquered Italian Empire in East Africa as a result of the Second Italo-Abyssinian War. She was constructed under the order of the 1938 Naval Expansion Program, along with her sister ship Roma.

The Francesco Caracciolo-class battleships were a group of four super-dreadnought battleships designed for the Regia Marina in 1913 and ordered in 1914. The first ship of the class, Francesco Caracciolo, was laid down in late 1914; the other three ships, Cristoforo Colombo, Marcantonio Colonna, and Francesco Morosini followed in 1915. Armed with a main battery of eight 381 mm (15 in) guns and possessing a top speed of 28 knots, the four ships were intended to be the equivalent of the fast battleships like the British Queen Elizabeth class.

The Yugoslav destroyer Split was a large destroyer designed for the Royal Yugoslav Navy in the late 1930s. Construction began in 1939, but she was captured incomplete by the Italians during the invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941. They continued to build the ship, barring a brief hiatus, but she was not completed before she was scuttled after the Italian surrender in September 1943. The Germans occupied Split and refloated the destroyer later that year, but made no efforts to continue work. The ship was scuttled again before the city was taken over by the Yugoslav Partisans in late 1944. Split was refloated once more, but the new Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was able to do little with her before the Tito–Stalin Split in 1948 halted most work. Aid and equipment from the United States and the United Kingdom finally allowed her to be completed 20 years after construction began. She was commissioned in July 1958 and served as the navy's flagship for most of her career. Split became a training ship in the late 1970s after a boiler explosion. She was decommissioned in 1980, and scrapped six years later.

Faà di Bruno was an Italian monitor built during World War I. Completed in 1917, the ship played a small role in the 11th Battle of the Isonzo later that year. She was decommissioned in 1924, but returned to service as the floating battery GM 194 at the beginning of World War II and was towed to Genoa and where she spent the rest of the war. The ship had her guns disabled when the Royal Navy bombarded Genoa in 1941. GM 194 was captured by the Germans after the Italian Armistice in 1943 and was turned over to the puppet Repubblica Sociale Italiana that they installed afterward. She was scuttled at the end of the war and subsequently scrapped.

Pola was a Zara-class heavy cruiser of the Italian Regia Marina, named after the Italian city of Pola. She was built in the Odero Terni Orlando shipyard in Livorno in the early 1930s and entered service in 1932. She was the fourth and last ship in the class, which also included Zara, Fiume, and Gorizia. Compared to her sisters, Pola was built as a flagship with a larger conning tower to accommodate an admiral's staff. Like her sisters, she was armed with a battery of eight 203-millimeter (8.0 in) guns and was capable of a top speed of 32 knots.

Fiume was a Zara-class heavy cruiser of the Italian Regia Marina, named after the Italian city of Fiume, she was the second of four ships in the class, and was built between April 1929 and November 1931. Armed with a main battery of eight 8-inch (200 mm) guns, she was nominally within the 10,000-long-ton (10,000 t) limit imposed by the Washington Naval Treaty, though in reality she significantly exceeded this figure.

Quarto was a unique protected cruiser built by the Italian Regia Marina in the 1910s. Her keel was laid in November 1909, she was launched in August 1911, and was completed in March 1913. She was the first Italian cruiser to be equipped with steam turbines, which gave her a top speed of 28 knots. Her high speed was a requirement for the role in which she was designed to serve: a scout for the main Italian fleet.