Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including nation-states, and capitalism. Anarchism advocates for the replacement of the state with stateless societies and voluntary free associations. As a historically left-wing movement, this reading of anarchism is placed on the farthest left of the political spectrum, usually described as the libertarian wing of the socialist movement.

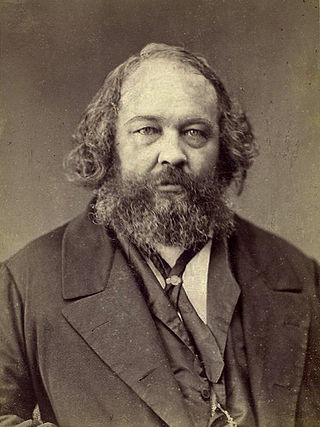

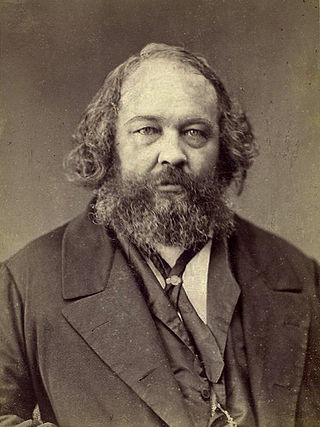

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin was a Russian revolutionary anarchist. He is among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major figure in the revolutionary socialist, social anarchist, and collectivist anarchist traditions. Bakunin's prestige as a revolutionary also made him one of the most famous ideologues in Europe, gaining substantial influence among radicals throughout Russia and Europe.

Anarchism and violence have been linked together by events in anarchist history such as violent revolution, terrorism, assassination attempts and propaganda of the deed. Propaganda of the deed, or attentát, was espoused by leading anarchists in the late 19th century and was associated with a number of incidents of political violence. Anarchist thought, however, is quite diverse on the question of violence. Where some anarchists have opposed coercive means on the basis of coherence, others have supported acts of violent revolution as a path toward anarchy. Anarcho-pacifism is a school of thought within anarchism which rejects all violence.

Anarcho-pacifism, also referred to as anarchist pacifism and pacifist anarchism, is an anarchist school of thought that advocates for the use of peaceful, non-violent forms of resistance in the struggle for social change. Anarcho-pacifism rejects the principle of violence which is seen as a form of power and therefore as contradictory to key anarchist ideals such as the rejection of hierarchy and dominance. Many anarcho-pacifists are also Christian anarchists, who reject war and the use of violence.

The history of anarchism is ambiguous, primarily due to the ambiguity of anarchism itself. Scholars find it hard to define or agree on what anarchism means, which makes outlining its history difficult. There is a range of views on anarchism and its history. Some feel anarchism is a distinct, well-defined 19th and 20th century movement while others identify anarchist traits long before first civilisations existed.

Moral economy is a way of viewing economic activity in terms of its moral, rather than material, aspects. The concept was developed in 1971 by British Marxist social historian and political activist E. P. Thompson in his essay, "The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century". He referred to a specific class struggle in a specific era, seen from the perspective of the poorest citizens—the "crowd".

Black anarchism is a term applied to a group of people of African descent who identify with the principles of anarchism. These people include, but are not limited to, Ashanti Alston, Kuwasi Balagoon, Lorenzo Kom'boa Ervin, Greg Jackson, and Martin Sostre. Critics of the term suggest that it broadly eclipses important political differences between these multi-varied thinkers and incorrectly presents them as having a shared theory or movement. Black anarchism has had a major influence on the anarchist movement, black anarchists have a 100-year history in black-led anti-fascist and anti-racist history.

Anarchism in Mexico, the anarchist movement in Mexico, extends from Plotino Rhodakanaty's organization of peasant workers in the 1890s, to Ricardo Flores Magón's activism prior to the Mexican Revolution, to the punk subcultures of the 1990s.

A stateless society is a society that is not governed by a state. In stateless societies, there is little concentration of authority; most positions of authority that do exist are very limited in power and are generally not permanently-held positions; and social bodies that resolve disputes through predefined rules tend to be small. Different stateless societies feature highly variable economic systems and cultural practices.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to anarchism:

Anarchism in Vietnam first emerged in the early 20th century, as the Vietnamese started to fight against the French colonial government along with the puppet feudal dynasty for either independence or higher autonomy. Some famous radical figures such as Phan Bội Châu and Nguyễn An Ninh became exposed to strands of anarchism in Japan, China, and France. Anarchism reached its apex in Vietnam during the 1920s, but it soon began to lose its influence with the introduction of Marxism-Leninism and the beginning of the Vietnamese communist movement. In recent years, Anarchism in Vietnam has attracted new adherents.

Total liberation, also referred to as total liberation ecology or veganarchism, is a political philosophy and movement that combines anarchism with a commitment to animal and earth liberation. Whilst more traditional approaches to anarchism have often focused primarily on opposing the state and capitalism, total liberation is additionally concerned with opposing all additional forms of human oppression as well as the oppression of other animals and ecosystems. Proponents of total liberation typically espouse a holistic and intersectional approach aimed at using direct action to dismantle all forms of domination and hierarchy, common examples of which include the state, capitalism, patriarchy, racism, heterosexism, cissexism, disablism, ageism, speciesism and ecological domination.

Eric Tagliacozzo is the John Stambaugh Professor of History at Cornell University, where he teaches Southeast Asian history. He is the director of Cornell's Comparative Muslim Societies Program, the director of the Cornell Modern Indonesia Project, and the contributing editor of the journal Indonesia. Tagliacozzo received his B.A. from Haverford College in 1989 and his Ph.D. from Yale University in 1999. Tagliacozzo studied with Ben Kiernan, James C. Scott, and Jonathan Spence in the History Department at Yale University.

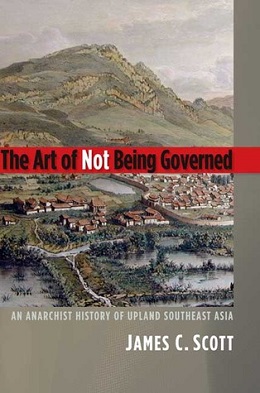

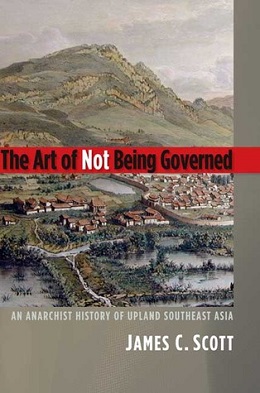

The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia is a book-length anthropological and historical study of the Zomia highlands of Southeast Asia written by James C. Scott published in 2009. Zomia, as defined by Scott, includes all the lands at elevations above 300 meters stretching from the Central Highlands of Vietnam to Northeastern India. That encompasses parts of Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Myanmar, as well as four provinces of China. Zomia's 100 million residents are minority peoples "of truly bewildering ethnic and linguistic variety", he writes. Among them are the Akha, Hmong, Karen, Lahu, Mien, and Wa peoples.

The term Southeast Asian Massif was proposed in 1997 by anthropologist Jean Michaud to discuss the human societies inhabiting the lands above an elevation of approximately 300 metres (1,000 ft) in the southeastern portion of the Asian landmass, thus not merely in the uplands of conventional Mainland Southeast Asia. It concerns highlands overlapping parts of 10 countries: southwest China, Northeast India, eastern Bangladesh, and all the highlands of Myanmar (Burma), Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Peninsular Malaysia, and Taiwan. The indigenous population encompassed within these limits numbers approximately 100 million, not counting migrants from surrounding lowland majority groups who came to settle in the highlands over the last few centuries.

Bao Jingyan or Pao Ching-yen was a Chinese, libertarian/anarchist philosopher and Taoist who lived somewhere between the late 200's AD and before 400 AD.

Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance is a 1985 book on everyday forms of rural class conflict as illustrated in a Malaysian village, written by anthropologist James C. Scott and published by Yale University Press.

The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebellion and Subsistence in Southeast Asia is a 1976 book by James C. Scott on the nature of subsistence ethics in peasant cultures. He asserts that peasants prefer the stability of state or landlord protection of minimal subsistence over the risky instability of self-subsistence, producing a feudal moral economy. Where colonialism and introductions of market economies interfere with this arrangement, peasants will rebel, separate from concerns about fluctuating quality of life. Scott cites three 1930s rebellions as examples: Cochinchina, the Burmese Saya San Rebellion, and the Vietnamese Nghệ-Tĩnh Soviets.

Anarchism in the Philippines has its roots in the anti-colonial struggle against the Spanish Empire, becoming influential in the Philippine Revolution and the country's early trade unionist movement. After being supplanted by Marxism-Leninism as the leading revolutionary tendency during the mid-20th century, it experienced a resurgence as part of the punk subculture, following the fragmentation of the Communist Party of the Philippines.