Related Research Articles

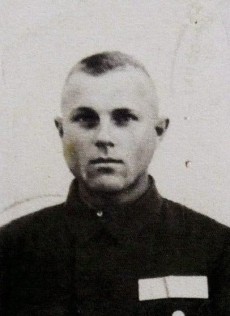

John Demjanjuk was a Ukrainian-American who served as a Trawniki man and Nazi camp guard at Sobibor extermination camp, Majdanek, and Flossenbürg. Demjanjuk became the center of global media attention in the 1980s, when he was tried and convicted in Israel after being misidentified as "Ivan the Terrible", a notoriously cruel watchman at Treblinka extermination camp. In 1993 the verdict was overturned. Shortly before his death, he was tried and convicted in the Federal Republic of Germany as an accessory to the 28,060 murders that occurred during his service at Sobibor.

Appalachia is a geographic region located in the central and southern sections of the Appalachian Mountains of the eastern United States. Its boundaries stretch from the western Catskill Mountains of New York into Pennsylvania, continuing on through the Blue Ridge Mountains and Great Smoky Mountains into northern Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi, with West Virginia being the only state in which the entire state is within the boundaries of Appalachia. In 2021, the region was home to an estimated 26.3 million people, of whom roughly 80% were white.

Edward Davis (Ed) Fagan is a former American reparations lawyer who was disbarred for his conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit, or misrepresentation.

The Legal Aid Society is a 501(c)(3) non-profit legal aid provider based in New York City. Founded in 1876, it is the oldest and largest provider of legal aid in the United States. Its attorneys provide representation on criminal and civil matters in both individual cases and class action lawsuits. The organization is funded through a combination of public grants and private donations. It is the largest recipient of funding among regional legal aid providers from the New York City government and is the city's primary legal services provider.

The American Jewish Congress (AJCongress) is an association of American Jews organized to defend Jewish interests at home and abroad through public policy advocacy, using diplomacy, legislation, and the courts.

In criminal law, the right to counsel means a defendant has a legal right to have the assistance of counsel and, if the defendant cannot afford a lawyer, requires that the government appoint one or pay the defendant's legal expenses. The right to counsel is generally regarded as a constituent of the right to a fair trial. Historically, however, not all countries have always recognized the right to counsel. The right is often included in national constitutions. Of the 194 constitutions currently in force, 153 have language to this effect.

The Jewish Labor Committee (JLC) is an American secular Jewish labor organization founded in 1934 to oppose the rise of Nazism in Germany. Among its central purposes is promoting labor union interests in the organized Jewish communities, especially in the USA, and Jewish interests within U.S. labor unions. The organization is headquartered in New York City, where it was founded, with local/regional offices in Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, Chicago and Los Angeles, and volunteer-led affiliated groups in other U.S. communities. Today, it works to maintain and strengthen the historically strong relationship between the American Jewish community and the trade union movement, and to promote what they see as the shared social justice agenda of both communities. The JLC was also active in Canada from 1936 until the 1970s.

Burt Neuborne is the Norman Dorsen Professor of Civil Liberties at New York University School of Law and the founding legal director of the Brennan Center for Justice.

The International Association of Jewish Lawyers and Jurists (IJL) strives to advance human rights everywhere, including the prevention of war crimes, the punishment of war criminals, the prohibition of weapons of mass destruction, and international co-operation based on the rule of law and the fair implementation of international covenants and conventions.

Stephen B. Bright is an American lawyer known for representing people facing the death penalty, advocating for the right to counsel for poor people accused of crimes, and challenging inhumane practices and conditions in prisons and jails. He has taught at Yale Law School since 1993 and has been teaching at the Georgetown Law Center since 2017. In 2016, he ended almost 35 years at the Southern Center for Human Rights in Atlanta, first as director from 1982 to 2005, and then as president and senior counsel from 2006 to 2016.

Arthur Kinoy was an American attorney and progressive civil rights leader who helped defend Ethel and Julius Rosenberg. He served as a professor of law at the Rutgers School of Law–Newark from 1964 to 1999. He was one of the founders in 1966 of the Center for Constitutional Rights in New York City, and successfully argued a number of cases before the Supreme Court of the United States. He also founded the Public Interest Law Center of New Jersey.

Texas RioGrande Legal Aid, formerly Texas Rural Legal Aid (TRLA), is a nonprofit agency that specializes in providing free civil legal services to the poor in a 68-county service area. It also operates a migrant farmworker legal assistance program in six southern states and a public defender program in southern rural counties of Texas. Established in 1970, TRLA is the largest legal aid provider in Texas and the second largest in the United States.

Appalachian Volunteers (AV) was a non-profit organization engaged in community development projects in central Appalachia that evolved into a controversial community organizing network, with a reputation that went "from self-help to sedition" as its staff developed from "reformers to radicals," teaching things from Marx, Lenin and Mao, in the words of one historian, in the brief period between 1964 and 1970 during the War on Poverty.

Samuel J. Dubbin is an American lawyer, public servant, and Holocaust Survivors' rights advocate. He is a principal in the law firm Dubbin & Kravetz, L.L.P., a former shareholder in the law firm Greenberg Traurig, and a former partner with Steel Hector & Davis. A Clinton Administration appointee, he served in the Department of Justice and Department of Transportation. He has received a Martindale-Hubbell Peer Review Rating of AV and is included in the Bar Register of Preeminent Lawyers.

Aryeh Neier is an American human rights activist who co-founded Human Rights Watch, served as the president of George Soros's Open Society Institute philanthropy network from 1993 to 2012, had been National Director of the American Civil Liberties Union from 1970 to 1978, and he was also involved with the creation of the group SDS by being directly involved in the group SLID's renaming.

Sparky (James) and Rhonda Rucker are a performing duo. They travel to various places to sing folk and traditional music. They have been nominated for musical awards. Combined, they have released 16 albums. Ten of these albums were together. Their album, Treasures and Tears, was in the running for an award. Their music style os vast including blues, Appalachian music, slave songs, storytelling, etc.

"Ivan the Terrible" is the nickname given to a notorious guard at the Treblinka extermination camp during the Holocaust. The moniker alluded to Ivan IV, also known as Ivan the Terrible, the infamous tsar of Russia. "Ivan the Terrible" gained international recognition following the 1986 John Demjanjuk case. By 1944, a cruel guard named "Ivan", sharing his distinct duties and extremely violent behavior with a guard named "Nicholas", was mentioned in survivor literature. Ukrainian–American John Demjanjuk was first accused of being Ivan the Terrible at the Treblinka concentration camp. Demjanjuk was found guilty of war crimes and was sentenced to death by hanging. Exculpatory material in the form of conflicting identifications from Soviet archives was subsequently released, identifying Ivan the Terrible as one Ivan Marchenko, leading the Supreme Court of Israel to acquit Demjanjuk in 1993 because of reasonable doubt. Demjanjuk was later extradited to Germany where he was convicted in 2011 of war crimes for having served at Sobibor extermination camp. While awaiting his appeal hearing, Demjanjuk died at the age of 91 in a nursing home. Under German law, his guilt was revoked, reinforcing his presumed innocence.

The Appalachian region and its people have historically been stereotyped by observers, with the basic perceptions of Appalachians painting them as backwards, rural, and anti-progressive. These widespread, limiting views of Appalachia and its people began to develop in the post-Civil War; Those who "discovered" Appalachia found it to be a very strange environment, and depicted its "otherness" in their writing. These depictions have persisted and are still present in common understandings of Appalachia today, with a particular increase of stereotypical imagery during the late 1950s and early 1960s in sitcoms. Common Appalachian stereotypes include those concerning economics, appearance, and the caricature of the "hillbilly."

In the United States, a public defender is a lawyer appointed by the courts and provided by the state or federal governments to represent and advise those who cannot afford to hire a private attorney. Public defenders are full-time attorneys employed by the state or federal governments. The public defender program is one of several types of criminal legal aid in the United States.

The city of Baltimore, Maryland includes a significant Appalachian population. The Appalachian community has historically been centered in the neighborhoods of Hampden, Pigtown, Remington, Woodberry, Lower Charles Village, Highlandtown, and Druid Hill Park, as well as the Baltimore inner suburbs of Dundalk, Essex, and Middle River. The culture of Baltimore has been profoundly influenced by Appalachian culture, dialect, folk traditions, and music. People of Appalachian heritage may be of any race or religion. Most Appalachian people in Baltimore are white or African-American, though some are Native American or from other ethnic backgrounds. White Appalachian people in Baltimore are typically descendants of early English, Irish, Scottish, Scotch-Irish, and Welsh settlers. A migration of White Southerners from Appalachia occurred from the 1920s to the 1960s, alongside a large-scale migration of African-Americans from the Deep South and migration of Native Americans from the Southeast such as the Lumbee and the Cherokee. These out-migrations caused the heritage of Baltimore to be deeply influenced by Appalachian and Southern cultures.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gayle., Donahue, Arwen, 1969- Howell, Rebecca (2009). This is home now : Kentucky's Holocaust survivors speak. Univ. Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-7342-9. OCLC 401854512.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Rosenberg, John. "Reflections on bringing Justice to the Citizens of Appalachia". Management Information Exchange.

- 1 2 3 4 "Our History". AppalReD Legal Aid. 2015-10-21. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- ↑ Rosenberg, John. "Eastern Kentucky Advocate: A Q&A with Attorney John M. Rosenberg". The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. 118: 95–107 – via Project MUSE.

- 1 2 3 4 Rosenberg, John. "Personal Reflections of a Life in Public Interest Law: From the Civil Rights Division of the United States Department of Justice to Appalred". West Virginia Law Review. 96: 316–331.

- 1 2 3 Winnerip, Michael (1997-06-29). "What's a Nice Jewish Lawyer Like John Rosenberg Doing in Appalachia? (Published 1997)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331 . Retrieved 2021-03-05.