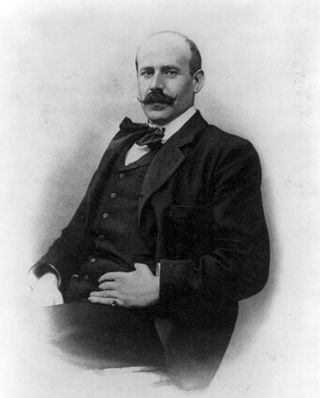

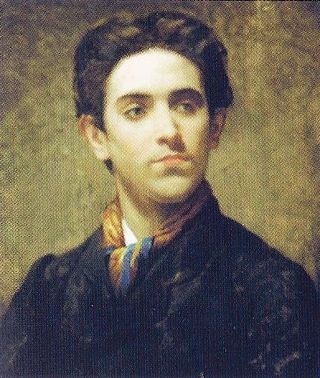

Ignacio Zuloaga y Zabaleta was a Spanish painter, born in Eibar, Guipuzcoa, near the monastery of Loyola.

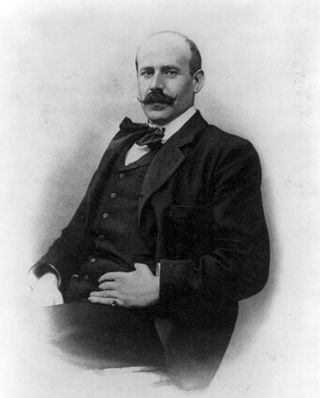

William Thomas Beckford was an English novelist, art critic, planter and politician. He was reputed at one stage to be England's richest commoner.

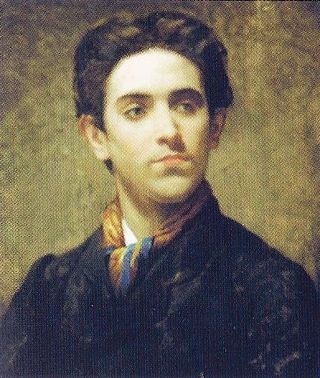

Juan Prim y Prats, 1st Count of Reus, 1st Marquis of los Castillejos, 1st Viscount of Bruch was a Spanish general and statesman who was briefly Prime Minister of Spain until his assassination.

Eibar is a city and municipality within the province of Gipuzkoa, in the Autonomous Community of Euskadi. It is the capital of the eskualde / comarca of Debabarrena.

Léonard Morel-Ladeuil, French goldsmith and sculptor, was born at Clermont-Ferrand.

Champlevé is an enamelling technique in the decorative arts, or an object made by that process, in which troughs or cells are carved, etched, die struck, or cast into the surface of a metal object, and filled with vitreous enamel. The piece is then fired until the enamel fuses, and when cooled the surface of the object is polished. The uncarved portions of the original surface remain visible as a frame for the enamel designs; typically they are gilded in medieval work. The name comes from the French for "raised field", "field" meaning background, though the technique in practice lowers the area to be enamelled rather than raising the rest of the surface.

Damascening is the art of inlaying different metals into one another—typically, gold or silver into a darkly oxidized steel background—to produce intricate patterns similar to niello. The English term comes from a perceived resemblance to the rich tapestry patterns of damask silk. The term is also used to describe the use of inlaid copper interconnects in integrated circuits. As its name suggests, damascene gets its name from Damascus, Syria and the ancient artisans that created and exported this craft.

The National Archaeological Museum is a archaeology museum in Madrid, Spain. It is located on Calle de Serrano beside the Plaza de Colón, sharing its building with the National Library of Spain. It is one of the National Museums of Spain and it is attached to the Ministry of Culture.

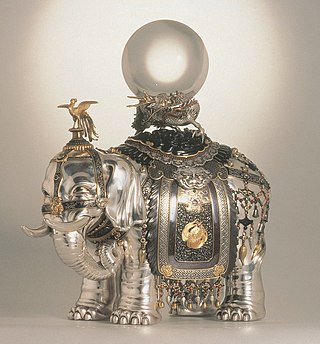

Sir Nasser David Khalili KCSS is a British scholar, collector, and philanthropist based in London. Born in Iran and educated at Queens College, City University of New York and the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, he is a naturalised British citizen.

The Fonthill Vase, also called the Gaignières-Fonthill Vase after François Roger de Gaignières and William Beckford's Fonthill Abbey, is a bluish-white Qingbai Chinese porcelain vase dated to 1300–1340 AD. It is famous as the earliest documented Chinese porcelain object to have reached Europe.

In 1898, Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild bequeathed to the British Museum as the Waddesdon Bequest the contents from his New Smoking Room at Waddesdon Manor. This consisted of a wide-ranging collection of almost 300 objets d'art et de vertu, which included exquisite examples of jewellery, plate, enamel, carvings, glass and maiolica. One of the earlier objects is the outstanding Holy Thorn Reliquary, probably created in the 1390s in Paris for John, Duke of Berry. The collection is in the tradition of a schatzkammer, or treasure house, such as those formed by the Renaissance princes of Europe; indeed, the majority of the objects are from late Renaissance Europe, although there are several important medieval pieces, and outliers from classical antiquity and medieval Syria.

The Sanctuary of Loyola or Loiola, or the Shrine and Basilica of Loyola, consists of a series of edifices built in Churrigueresque Baroque style around the birthplace of St. Ignatius of Loyola, founder of the Society of Jesus.

Daniel Zuloaga y Boneta was a Spanish ceramist and painter. He is considered to be one of the innovators of art pottery in Spain. He worked primarily from his workshops in Madrid and Segovia, but his work extended throughout Spain. He participated in various international exhibitions, and his pieces can be found in other European countries. His work was characterized by using ancient techniques. Through the influence of his father, Zuloaga worked in his youth at the Royal Palace of Madrid. After training in France, Zuloaga and his brothers opened their first shop in the Real Fábrica de La Moncloa, its most representative work being the facades of the Palacio de Velázquez. His other works can be seen at the Palacio de Cristal and the Hospital of Maudes, among many others.

Alfred Morrison was an English collector, known for his interest in works of art, autographs and manuscripts.

The Khalili Collections are eight distinct art collections assembled by Nasser D. Khalili over five decades. Together, the collections include some 35,000 works of art, and each is considered among the most important in its field.

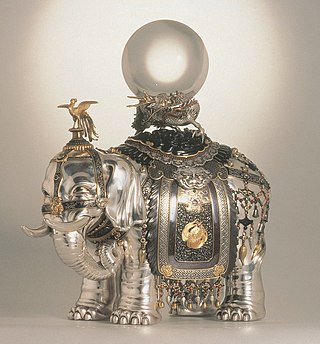

The Khalili Collection of Japanese Art is a private collection of decorative art from Meiji-era (1868–1912) Japan, assembled by the British scholar, collector and philanthropist Nasser D. Khalili. Its 2,200 art works include metalwork, enamels, ceramics, lacquered objects, and textile art, making it comparable only to the collection of the Japanese imperial family in terms of size and quality. The Meiji era was a time when Japan absorbed some Western cultural influences and used international events to promote its art, which became very influential in Europe. Rather than covering the whole range of Meiji-era decorative art, Khalili has focused on objects of the highest technical and artistic quality. Some of the works were made by artists of the imperial court for the Great Exhibitions of the late 19th century. The collection is one of eight assembled, published, and exhibited by Khalili.

Plácido Maria Martin Zuloaga y Zuloaga was a Spanish sculptor and metalworker. He is known for refining damascening, a technique that involves inlaying gold, silver, and other metals into an iron surface, creating an intricate decorative effect. Zuloaga came from a family of Basque metalworkers. He was the son of damascening pioneer Eusebio Zuloaga, the half-brother of the artist Daniel Zuloaga, and the father of the painter Ignacio Zuloaga. Taking over his father's armaments factory, he adapted it to make art pieces which he exhibited at international fairs, winning multiple awards.

The Khalili Collection of Enamels of the World is a private collection of enamel artworks from the period 1700 to 2000, assembled by the British scholar, collector and philanthropist Nasser D. Khalili. It is one of the eight Khalili Collections, each of which is considered among the most important in its field.

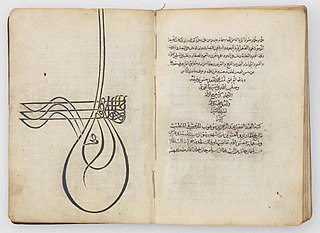

The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art includes 26,000 objects documenting Islamic art over a period of almost 1400 years, from 700 AD to the end of the twentieth century. It is the largest of the Khalili Collections: eight collections assembled, conserved, published and exhibited by the British scholar, collector and philanthropist Nasser David Khalili, each of which is considered among the most important in its field. Khalili's collection is one of the most comprehensive Islamic art collections in the world and the largest in private hands.

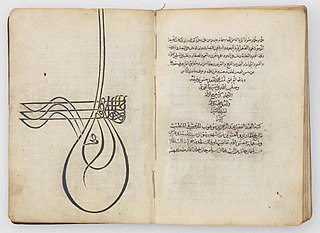

Empire of the Sultans: Ottoman Art of the Khalili Collection was a 1995–2004 touring exhibition displaying objects from the Khalili Collection of Islamic Art. Around two hundred exhibits, including calligraphy, textiles, pottery, weapons, and metalwork, illustrated the art and daily life of six centuries of the Ottoman Empire. Many of the objects had been created for the leaders of the empire, the sultans. Two of the calligraphic pieces were the work of sultans themselves.