The Peloponnese, Peloponnesus, or Morea is a peninsula and geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridge which separates the Gulf of Corinth from the Saronic Gulf. From the late Middle Ages until the 19th century the peninsula was known as the Morea, a name still in colloquial use in its demotic form.

During the late Middle Ages, the two cities of Argos and Nauplia formed a lordship within the Frankish-ruled Morea in southern Greece.

The Great Turkish War, also called the Wars of the Holy League, was a series of conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and the Holy League consisting of the Holy Roman Empire, Poland-Lithuania, Venice, Russia, and the Kingdom of Hungary. Intensive fighting began in 1683 and ended with the signing of the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699. The war was a defeat for the Ottoman Empire, which for the first time lost large amounts of territory, in Hungary and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, as well as part of the western Balkans. The war was significant also by being the first time that Russia was involved in an alliance with Western Europe.

The Morean War, also known as the Sixth Ottoman–Venetian War, was fought between 1684–1699 as part of the wider conflict known as the "Great Turkish War", between the Republic of Venice and the Ottoman Empire. Military operations ranged from Dalmatia to the Aegean Sea, but the war's major campaign was the Venetian conquest of the Morea (Peloponnese) peninsula in southern Greece. On the Venetian side, the war was fought to avenge the loss of Crete in the Cretan War (1645–1669). It happened while the Ottomans were entangled in their northern struggle against the Habsburgs – beginning with the failed Ottoman attempt to conquer Vienna and ending with the Habsburgs gaining Buda and the whole of Hungary, leaving the Ottoman Empire unable to concentrate its forces against the Venetians. As such, the Morean War was the only Ottoman–Venetian conflict from which Venice emerged victorious, gaining significant territory. Venice's expansionist revival would be short-lived, as its gains would be reversed by the Ottomans in 1718.

The Seventh Ottoman–Venetian War was fought between the Republic of Venice and the Ottoman Empire between 1714 and 1718. It was the last conflict between the two powers, and ended with an Ottoman victory and the loss of Venice's major possession in the Greek peninsula, the Peloponnese (Morea). Venice was saved from a greater defeat by the intervention of Austria in 1716. The Austrian victories led to the signing of the Treaty of Passarowitz in 1718, which ended the war.

The Cretan War, also known as the War of Candia or the Fifth Ottoman–Venetian War, was a conflict between the Republic of Venice and her allies against the Ottoman Empire and the Barbary States, because it was largely fought over the island of Crete, Venice's largest and richest overseas possession. The war lasted from 1645 to 1669 and was fought in Crete, especially in the city of Candia, and in numerous naval engagements and raids around the Aegean Sea, with Dalmatia providing a secondary theater of operations.

The Frankokratia, also known as Latinokratia and, for the Venetian domains, Venetokratia or Enetokratia, was the period in Greek history after the Fourth Crusade (1204), when a number of primarily French and Italian states were established by the Partitio terrarum imperii Romaniae on the territory of the dissolved Byzantine Empire.

The Stato da Màr or Domini da Mar was the name given to the Republic of Venice's maritime and overseas possessions from around 1000 to 1797, including at various times parts of what are now Istria, Dalmatia, Montenegro, Albania, Greece and notably the Ionian Islands, Peloponnese, Crete, Cyclades, Euboea, as well as Cyprus.

The First Ottoman–Venetian War was fought between the Republic of Venice with its allies and the Ottoman Empire from 1463 to 1479. Fought shortly after the capture of Constantinople and the remnants of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottomans, it resulted in the loss of several Venetian holdings in Albania and Greece, most importantly the island of Negroponte (Euboea), which had been a Venetian protectorate for centuries. The war also saw the rapid expansion of the Ottoman navy, which became able to challenge the Venetians and the Knights Hospitaller for supremacy in the Aegean Sea. In the closing years of the war, however, the Republic managed to recoup its losses by the de facto acquisition of the Crusader Kingdom of Cyprus.

The Eyalet of the Morea was a first-level province (eyalet) of the Ottoman Empire, centred on the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece.

The Battle of the Echinades was fought in 1427 among the Echinades islands off western Greece between the fleets of Carlo I Tocco and the Byzantine Empire. The battle was a decisive Byzantine victory, the last in the Empire's naval history, and led to the consolidation of the Peloponnese under the Byzantine Despotate of the Morea.

The siege of Corfu took place on 8 July – 21 August 1716, when the Ottoman Empire besieged the city of Corfu, on the namesake island, then held by the Republic of Venice. The siege was part of the Seventh Ottoman–Venetian War, and, coming in the aftermath of the lightning conquest of the Morea by the Ottoman forces in the previous year, was a major success for Venice, representing its last major military success and allowing it to preserve its rule over the Ionian Islands.

The siege of Negroponte was undertaken by the forces of the Republic of Venice from July to October 1688. The Venetian army, composed of several mercenary and allied contingents from western Europe, had succeeded in capturing the Peloponnese in the previous years, and proceeded to capture Athens and attack Negroponte, the main Ottoman stronghold in Central Greece. The Venetian siege was hampered by the Ottoman resistance and their inability to completely isolate the town, as the Ottoman general Ismail Pasha managed to ferry supplies to the besieged garrison. Furthermore, the Venetian army suffered many casualties from an outbreak of the plague in the Venetian camp, which led to the death of 4,000 troops and the experienced general Otto Wilhelm Königsmarck. The departure of the Florentine and Maltese contingents further weakened the Venetians, and when the German mercenaries refused to remain there in winter quarters, the Venetian commander, Doge Francesco Morosini, had to concede defeat and retreat to the Peloponnese.

The Treaty of Sapienza was concluded in June 1209 between the Republic of Venice and the newly established Principality of Achaea, under Prince Geoffrey I of Villehardouin, concerning the partition of the Peloponnese (Morea) peninsula, conquered following the Fourth Crusade. By its terms, Venice, which had been accorded most of the Peloponnese in the Partitio Romaniae, recognized Villehardouin in possession of the entire peninsula except for the two forts of Modon and Coron, which came under Venetian control, and secured commercial and tax privileges in the Principality. The text of the treaty is also a valuable primary source for the early history of the Principality of Achaea.

The siege of the Acropolis took place on 23–29 September 1687, as the Venetian army under Otto Wilhelm Königsmarck laid siege to the Acropolis of Athens, held by the Ottoman garrison of the city. The siege resulted in the destruction of a large part of the Parthenon, which the Ottomans used as a gunpowder store.

Alvise Loredan was a Venetian nobleman of the Loredan family. At a young age he became a galley captain, and served with distinction as a military commander, with a long record of battles against the Ottomans, from the naval expeditions to aid Thessalonica, to the Crusade of Varna, and the opening stages of the Ottoman–Venetian War of 1463–1479, as well as the Wars in Lombardy against the Duchy of Milan. He also served in a number of high government positions, as provincial governor, savio del consiglio, and Procuratore de Supra of Saint Mark's Basilica.

Vettore Cappello was a merchant, statesman and military commander of the Republic of Venice. After an early career as a merchant that gained him substantial wealth, he began his political career in 1439. His ascent to higher offices was rapid. He is chiefly remembered for his advocacy of a decisive policy against the Ottoman Empire, and his command of Venetian forces as Captain General of the Sea during the lead-up to and the first stages of the First Ottoman–Venetian War.

The Ottoman reconquest of the Morea took place in June–September 1715, during the Seventh Ottoman–Venetian War. The Ottoman army, under Grand Vizier Silahdar Damat Ali Pasha, aided by the fleet under Kapudan Pasha Canım Hoca Mehmed Pasha, conquered the Morea peninsula in southern Greece, which had been captured by the Republic of Venice in the 1680s, during the Sixth Ottoman–Venetian War. The Ottoman reconquest inaugurated the second period of Ottoman rule in the Morea, which ended with the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence in 1821.

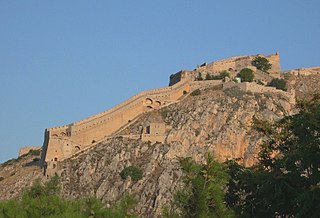

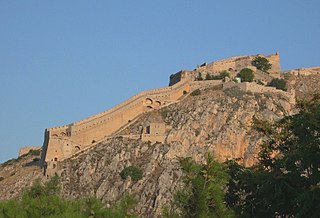

The siege of Nauplia took place on 12–20 July 1715, when the Ottoman Empire captured the city of Nauplia, the capital of the Republic of Venice's "Kingdom of the Morea" in southern Greece. Although Nauplia was strongly fortified and had been further strengthened with the construction of Palamidi fortress by the Venetians, the Ottomans managed to overcome them, largely through the treasonous assistance of the French colonel La Salle. The Ottomans exploded a mine and took Palamidi by storm on 20 July. The Venetian defenders retreated in panic, leading to the rapid fall of Acronauplia and the rest of the city. The garrison and populace were massacred or carried off as prisoners. The fall of Nauplia signalled the effective end of Venetian resistance to the Ottoman reconquest of the Morea, which was completed by 7 September.

Girolamo Corner or Cornaro was a Venetian nobleman and statesman. He served in high military posts during the Morean War against the Ottoman Empire, leading the Venetian conquest of Castelnuovo and Knin in Dalmatia, the capture of Monemvasia in Greece and of Valona and Kanina in Albania.