Gentile Bellini was an Italian painter of the school of Venice. He came from Venice's leading family of painters, and at least in the early part of his career was more highly regarded than his younger brother Giovanni Bellini, the reverse of the case today. From 1474 he was the official portrait artist for the Doges of Venice, and as well as his portraits he painted a number of very large subjects with multitudes of figures, especially for the Scuole Grandi of Venice, wealthy confraternities that were very important in Venetian patrician social life.

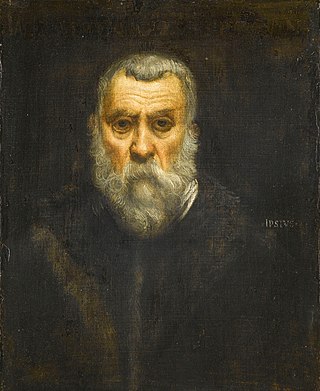

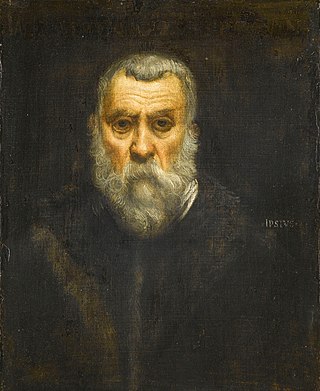

Jacopo Robusti, best known as Tintoretto, was an Italian painter identified with the Venetian school. His contemporaries both admired and criticized the speed with which he painted, and the unprecedented boldness of his brushwork. For his phenomenal energy in painting he was termed il Furioso. His work is characterised by his muscular figures, dramatic gestures and bold use of perspective, in the Mannerist style.

The Grand Canal is a channel in Venice, Italy. It forms one of the major water-traffic corridors in the city.

Vittore Carpaccio (UK: /kɑːrˈpætʃ oʊ/, US: /-ˈpɑːtʃ-/, Italian: [vitˈtoːre karˈpattʃo]; was an Italian painter of the Venetian school who studied under Gentile Bellini. Carpaccio was largely influenced by the style of the early Italian Renaissance painter Antonello da Messina, as well as Early Netherlandish painting. Although often compared to his mentor Gentile Bellini, Vittore Carpaccio's command of perspective, precise attention to architectural detail, themes of death, and use of bold color differentiated him from other Italian Renaissance artists. Many of his works display the religious themes and cross-cultural elements of art at the time; his portrayal of St. Augustine in His Study from 1502, reflects the popularity of collecting "exotic" and highly desired objects from different cultures.

The Gallerie dell'Accademia is a museum gallery of pre-19th-century art in Venice, northern Italy. It is housed in the Scuola della Carità on the south bank of the Grand Canal, within the sestiere of Dorsoduro. It was originally the gallery of the Accademia di Belle Arti di Venezia, the art academy of Venice, from which it became independent in 1879, and for which the Ponte dell'Accademia and the Accademia boat landing station for the vaporetto water bus are named. The two institutions remained in the same building until 2004, when the art school moved to the Ospedale degli Incurabili.

The Scuola Grande di San Rocco is a building in Venice, northern Italy. It is noted for its collection of paintings by Tintoretto and generally agreed to include some of his finest work.

The Scuola Grande di San Marco is a building in Venice, Italy, designed by the well-known Venetian architects Pietro Lombardo, Mauro Codussi, and Bartolomeo Bon. It was originally the home to one of the Scuole Grandi of Venice, or six major confraternities, but is now the city's hospital. It faces the Campo Santi Giovanni e Paolo, one of the largest squares in the city.

San Silvestro is a church building in the sestiere of San Polo of Venice, northern Italy.

The Miracle of the Slave is a painting completed in 1548 by the Italian Renaissance artist Jacopo Tintoretto. Originally commissioned for the Scuola Grande di San Marco, a confraternity in the city of Venice, the work has been held in the Gallerie dell'Accademia since 1815.

The Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista is a confraternity building located in the San Polo sestiere of the Italian city of Venice. Founded in the 13th century by a group of flagellants it was later to become one of the five Scuole Grandi of Venice. These organisations provided a variety of charitable functions in the city as well as becoming patrons of the arts. The Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista is notable for housing a relic of the true cross and for the series of paintings it commissioned from a number of famous Venetian artists depicting Miracles of the Holy Cross. No longer in the school, these came into public ownership during the Napoleonic era and are now housed in the Gallerie dell'Accademia. The scuola is open to visitors on a limited number of days, detailed on the official website.

The Legend of Saint Ursula is a series of large wall-paintings on canvas by the Italian Renaissance artist Vittore Carpaccio, commissioned by the Loredan family and originally created for the Scuola di Sant'Orsola (Ursula) in Venice, which was under their patronage. They are now in the Gallerie dell'Accademia in Venice.

The Senate, formally the Consiglio dei Pregadi or Rogati, was the main deliberative and legislative body of the Republic of Venice.

The Scuola dei Greci was the confraternity of the Greek community in Venice. Its members were primarily Greeks, but also included Serbs.

The Procession in St. Mark's Square is a tempera-on-canvas painting by Italian Renaissance artist Gentile Bellini, dating from c. 1496. It is housed in the Gallerie dell'Accademia in Venice.

The Scuola di Santa Maria degli Albanesi was a confraternity, a Scuola Piccola, for Albanian Christians Catholics, in Venice, northern Italy. Its building subsists.

St. Mark Preaching in Alexandria is an oil painting by the Italian Renaissance artists Gentile and Giovanni Bellini, dated to 1504–1507, and held in the Pinacoteca di Brera, in Milan.

The Canton Synagogue is one of five synagogues in the Jewish Ghetto of Venice, Italy. Established only four years after the nearby Scuola Grande Tedesca (1528), it is the second oldest Venetian synagogue. Its origins are uncertain: it might have been constructed as a prayer room for a group of Provençal Jews soon after their arrival in Venice, or as a private synagogue for a prominent local family. Repeatedly remodeled throughout its history, its interior is predominantly decorated in the Baroque and Rococo styles.

Save Venice Inc. is a U.S. non-profit organization dedicated to the conservation of art and architecture and the preservation of cultural heritage sites in Venice, Italy. Headquartered in New York City, it has an office in Venice, a chapter in Boston, and supporters across the United States and Europe.

Scuola is part of the name of many primary and secondary schools in Italy, Italian-language schools abroad, and institutes of tertiary education in Italy. Those are not listed in this disambiguation article. It may also refer to:

The Scuole Piccole of Venice are confraternities in the Republic of Venice. Unlike the more famous Scuole Grandi, membership in them was not restricted to citizens and indeed some of them were formed specifically for foreigners. Most Scuole, the scolae communes, were devoted to a particular saint or devotional cult, but some, the scuole delle arti, were associated with specific crafts or trade guild, and often obligatory for the members of that trade.