Sir Henry Bessemer was an English inventor, whose steel-making process would become the most important technique for making steel in the nineteenth century for almost one hundred years from 1856 to 1950. He also played a significant role in establishing the town of Sheffield, nicknamed ‘Steel City’, as a major industrial centre.

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured; white cast iron has carbide impurities which allow cracks to pass straight through, grey cast iron has graphite flakes which deflect a passing crack and initiate countless new cracks as the material breaks, and ductile cast iron has spherical graphite "nodules" which stop the crack from further progressing.

Sir Thomas Bouch was a British railway engineer. He was born in Thursby, near Carlisle, Cumberland, and lived in Edinburgh. As manager of the Edinburgh and Northern Railway he introduced the first roll-on/roll-off train ferry service in the world. Subsequently as a consulting engineer, he helped develop the caisson and popularised the use of lattice girders in railway bridges. He was knighted after the successful completion of the first Tay Railway Bridge, but his reputation was destroyed by the subsequent Tay Bridge disaster, in which 75 people are believed to have died as a result of defects in design, construction and maintenance, for all of which Bouch was held responsible. He died within 18 months of being knighted.

The Tay Bridge carries the railway across the Firth of Tay in Scotland between Dundee and the suburb of Wormit in Fife. Its span is 2.75 miles. It is the second bridge to occupy the site.

John Rennie FRSE FRS was a Scottish civil engineer who designed many bridges, canals, docks and warehouses, and a pioneer in the use of structural cast-iron.

A crane is a type of machine, generally equipped with a hoist rope, wire ropes or chains, and sheaves, that can be used both to lift and lower materials and to move them horizontally. It is mainly used for lifting heavy objects and transporting them to other places. The device uses one or more simple machines to create mechanical advantage and thus move loads beyond the normal capability of a human. Cranes are commonly employed in transportation for the loading and unloading of freight, in construction for the movement of materials, and in manufacturing for the assembling of heavy equipment.

Britannia Bridge is a bridge in Wales that crosses the Menai Strait between the Isle of Anglesey and city of Bangor. It was originally designed and built by the noted railway engineer Robert Stephenson as a tubular bridge of wrought iron rectangular box-section spans for carrying rail traffic. Its importance was to form a critical link of the Chester and Holyhead Railway's route, enabling trains to directly travel between London and the port of Holyhead, thus facilitating a sea link to Dublin, Ireland.

The High Level Bridge is a road and railway bridge spanning the River Tyne between Newcastle upon Tyne and Gateshead in North East England. It is considered the most notable historical engineering work in the city. It was built by the Hawks family from 5,050 tons of iron. George Hawks, Mayor of Gateshead, drove in the last key of the structure on 7 June 1849, and the bridge was officially opened by Queen Victoria later that year.

The Conwy Railway Bridge carries the North Wales coast railway line across the River Conwy between Llandudno Junction and the town of Conwy. The wrought iron tubular bridge, which is now Grade I listed, was built in the 19th century. It is the last surviving example of this type of design by Stephenson after the original Britannia Bridge across the Menai Strait was partially destroyed in a fire in 1970 and rebuilt as a two-tier truss arch bridge design.

A tubular bridge is a bridge built as a rigid box girder section within which the traffic is carried. Famous examples include the original Britannia Bridge over the Menai Strait, the Conwy railway bridge over the River Conwy, designed and tested by William Fairbairn and built by Robert Stephenson between 1846 and 1850, and the original Victoria Bridge in Montreal.

The Dee Bridge disaster was a rail accident that occurred on 24 May 1847 in Chester, England, that resulted in five fatalities. It revealed the weakness of cast iron beam bridges reinforced by wrought iron tie bars, and brought criticism of its designer, Robert Stephenson, the son of George Stephenson.

The Tay Bridge disaster occurred during a violent storm on Sunday 28 December 1879, when the first Tay Rail Bridge collapsed as a North British Railway (NBR) passenger train on the Edinburgh to Aberdeen Line from Burntisland bound for its final destination of Dundee passed over it, killing all aboard. The bridge—designed by Sir Thomas Bouch—used lattice girders supported by iron piers, with cast iron columns and wrought iron cross-bracing. The piers were narrower and their cross-bracing was less extensive and robust than on previous similar designs by Bouch.

Captain Sir Samuel Brown of Netherbyres KH FRSE was an early pioneer of chain design and manufacture and of suspension bridge design and construction. He is best known for the Union Bridge of 1820, the first vehicular suspension bridge in Britain.

Cast-iron architecture is the use of cast iron in buildings and objects, ranging from bridges and markets to warehouses, balconies and fences. Refinements developed during the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th century made cast iron relatively cheap and suitable for a range of uses, and by the mid-19th century it was common as a structural material, and particularly for elaborately patterned architectural elements such as fences and balconies, until it fell out of fashion after 1900 as a decorative material, and was replaced by modern steel and concrete for structural purposes.

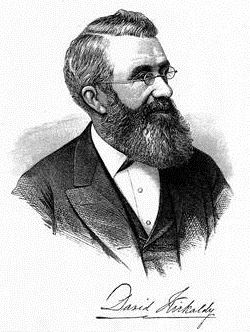

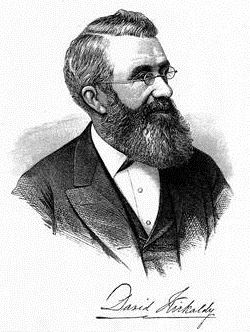

David Kirkaldy (1820–1897) was a Scottish engineer who pioneered the testing of materials as a service to engineers during the Victorian period. He established a test house in Southwark, London and built a large hydraulic tensile test machine, or tensometer for examining the mechanical properties of components, such as their tensile strength and tensile modulus or stiffness.

Sir William Arrol & Co. was a leading Scottish civil engineering and construction business founded by William Arrol and based in Glasgow. It built some of the most famous bridges in the United Kingdom including the second Tay Bridge, the Forth Bridge and Tower Bridge in London.

Structural engineering depends on the knowledge of materials and their properties, in order to understand how different materials resist and support loads.

Gaunless Bridge was a railway bridge on the Stockton and Darlington Railway. It was completed in 1823 and is one of the first railway bridges to be constructed of iron and the first to use an iron truss. It is also of an unusual lenticular truss design.

The Forth Bridge is a cantilever railway bridge across the Firth of Forth in the east of Scotland, 9 miles west of central Edinburgh. Completed in 1890, it is considered a symbol of Scotland, and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It was designed by English engineers Sir John Fowler and Sir Benjamin Baker. It is sometimes referred to as the Forth Rail Bridge, although this has never been its official name.

Ferry Bridge is a Victorian pedestrian bridge over the River Trent in Staffordshire, England. The bridge and its extension, the Stapenhill Viaduct, link Burton upon Trent town centre to the suburb of Stapenhill half a mile away on the other side of the river.