Tulu Nadu or Tulunad is a region and a proposed state on the southwestern coast of India. The Tulu people, known as 'Tuluva', speakers of Tulu, a Dravidian language, are the preponderant ethnic group of this region. South Canara, an erstwhile district and a historical area, encompassing the undivided territory of the contemporary Dakshina Kannada and Udupi districts of Karnataka State and Kasaragod district of Kerala state forms the cultural area of the Tuluver.

The Siddi, also known as the Sheedi, Sidi, or Siddhi, are an ethnic minority group inhabiting Pakistan and India. They are primarily descended from the Bantu peoples of the Zanj coast in Southeast Africa, most of whom came to the Indian subcontinent through the Arab Slave Trade. Others arrived as merchants, sailors, indentured servants, and mercenaries.

Beer in India has been prepared from rice or millet for thousands of years. In the 18th century, the British introduced European beer to India. Beer is not as popular as stronger alcoholic beverages like desi daru and Indian-made foreign liquor, such as Indian whiskey. The most popular beers in India are strong beers.

The Saharia, Sehariya, or Sahariya are an ethnic group in the state of Madhya Pradesh, India. The Saharias are mainly found in the districts of Morena, Sheopur, Bhind, Gwalior, Datia, Shivpuri, Vidisha and Guna districts of Madhya Pradesh and Baran district of Rajasthan.They are classified as Particularly vulnerable tribal group.

Solanki also known as Chaulukya is a clan name originally associated with the Rajputs in Northern India but which has also been borrowed by other communities such as the Saharias as a means of advancement by the process of sanskritisation. Other groups that use the name include the Bhils of Rajasthan, Koḷis, Ghān̄cīs, Kumbhārs, Bāroṭs, Kaḍiyās, Darjīs, Mocīs, Ḍheḍhs, and Bhangīs.

The Toto people are one of the world's smallest indigenous ethnic groups, living in a village of Totopara on India's border with Bhutan. Totos were nearly becoming extinct in the 1950s, but recent measures to safeguard their areas from being swamped with outsiders have helped preserve their unique heritage and also helped the population grow. The total population of Totos according to 1951 census was 321 living in 69 different houses at Totopara. In 1991 census, the Toto population had increased to 926 who lived in 180 different houses. In the 2001 census, their number had increased to 1184 - all living in Totopara.

Pratibha Ray is an Indian academic and writer of Odia-language novels and stories. For her contribution to the Indian literature, Ray received the Jnanpith Award in 2011. She was awarded the Padma Bhushan in 2022.

The Kambala, Kambla or Kambula is an annual buffalo race held in the southwestern Indian state of Karnataka. Traditionally, it is sponsored by local Tuluva landlords and households in the coastal districts of Dakshina Kannada and Udupi of Karnataka and Kasaragod of Kerala, a region collectively known as Tulu Nadu.

The Korava are a tribe in Tamil Nadu, India.

Asuri is an Austroasiatic language spoken by the Asur people, part of the Munda branch. Asuri has many Dravidian loanwords due to contact with Kurukh.

Asur people are a very small Austroasiatic ethnic group living primarily in the Indian state of Jharkhand, mostly in the Gumla, Lohardaga, Palamu and Latehar districts. They speak Asur language, which belongs to Munda family of Austro-asiatic languages.

The Hajong people are an ethnic group from Northeast India and northern parts of Bangladesh. The majority of the Hajongs are settled in India and are predominantly rice-farmers. They are said to have brought wet-field cultivation to Garo Hills, where the Garo people used slash and burn method of agriculture. Hajong have the status of a Scheduled Tribe in India and they are the fourth largest tribal ethnicity in the Indian state of Meghalaya.

The Puroik are a tribe of the hill-tracts of Arunachal Pradesh in India. They speak the Puroik language. The Puroik people are found in an estimated 53 villages in the districts of Subansiri and Upper Subansiri, Papumpare, Kurung Kumey and East Kameng along the upper reaches of the Par River. They number more than 10,000 people according to latest survey.

The Kuravar is an ethnic Tamil community native to the Kurinji mountain region of TamilNadu and Kerala, India.

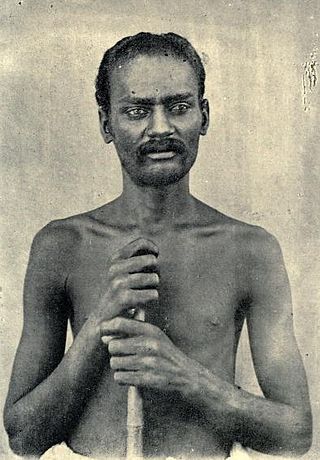

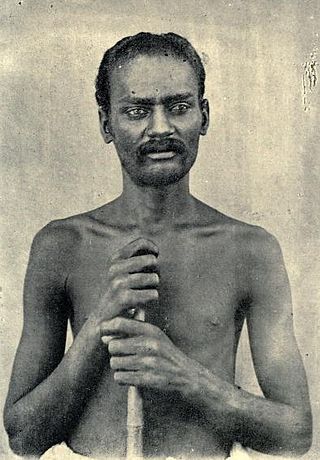

Hubbashika was a Koraga chieftain who ruled coastal areas of Karnataka and Kerala for 12 years during the 15th century CE.

A particularly vulnerable tribal group or PVTG, in the context of India, is a sub-classification of Scheduled Tribe or section of a Scheduled Tribe, that is considered more vulnerable than a regular Scheduled Tribe. The PVTG list was created by the Indian Government with the purpose of better improving the living standards of endangered tribal groups based on priority. PVTGs reside in 18 States and one union territory.

Kolam are a designated Scheduled Tribe in the Indian states of Telangana, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. They belong to the sub-category Particularly vulnerable tribal group, one of the three belonging to this sub-category, the others being Katkari and Madia Gond.

Devtamura is a hill range in South Tripura district of Tripura, India. It is known for an archaeological site of rock sculptures, a panel of carved images of Hindu deities of Durga, Ganesha and Kartikeya on the bank of Gomati River. The stone images are estimated to have curved during the 15/16th century.

Shompen hut is a village in the Nicobar district of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India. It is located in the Great Nicobar tehsil.

Yerukala or Erukala or Erukula is a tribal community primarily found in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. The population of Yerukala tribes according to 2011 census is 519,337. The total literacy rate among Yerukula is 48.12%. Most live in southern Coastal Andhra and Rayalaseema, with a smaller minority in districts of Telangana. Their native language is Yerukala, but most have shifted to Telugu. They were vilified in British sources for being habitual criminals, and so were placed under Criminal Tribes Act, although they were underrepresented in the population of criminals and were most likely targeted for their nomadic lifestyle.