The Kingdom of Dahomey was a West African kingdom located within present-day Benin that existed from approximately 1600 until 1904. It developed on the Abomey Plateau amongst the Fon people in the early 17th century and became a regional power in the 18th century by expanding south to conquer key cities like Whydah belonging to the Kingdom of Whydah on the Atlantic coast which granted it unhindered access to the Triangular trade.

Agaja was a king of the Kingdom of Dahomey, in present-day Benin, who ruled from 1718 until 1740. He came to the throne after his brother King Akaba. During his reign, Dahomey expanded significantly and took control of key trade routes for the Atlantic slave trade by conquering Allada (1724) and Whydah (1727). Wars with the powerful Oyo Empire to the east of Dahomey resulted in Agaja accepting tributary status to that empire and providing yearly gifts. After this, Agaja attempted to control the new territory of the kingdom of Dahomey through militarily suppressing revolts and creating administrative and ceremonial systems. Agaja died in 1740 after another war with the Oyo Empire and his son Tegbessou became the new king. Agaja is credited with creating many of the key government structures of Dahomey, including the Yovogan and the Mehu.

Tegbesu or Bossa Ahadee was a king of the Kingdom of Dahomey, in present-day Benin, from 1740 until 1774. While not the oldest son of King Agaja (1718-1740), he became king after Agaja's death following a succession struggle with a brother.

Agonglo was a King of the Kingdom of Dahomey, in present-day Benin, from 1789 until 1797. Agonglo took over from his father King Kpengla in 1789 and inherited many of the economic problems that developed during Kpengla's reign. Because of the poor economy, Agonglo was often constrained by domestic opposition. As a response, he reformed many of the economic policies and did military expeditions to try to increase the supply for the Atlantic slave trade. Many of these efforts were unsuccessful and European traders became less active in the ports of the kingdom. As a final effort, Agonglo accepted two Portuguese Catholic missionaries which resulted in a large outcry in royal circles and resulted in his assassination on May 1, 1797. Adandozan, his second oldest son, was named the new king.

Adandozan was a king of the Kingdom of Dahomey, in present-day Benin, from 1797 until 1818. His rule ended with a coup by his brother Ghezo who then erased Adandozan from the official history resulting in high uncertainty about many aspects of his life. Adandozan took over from his father Agonglo in 1797 but was quite young at the time and so there was a regent in charge of the kingdom until 1804. Dealing with the economic depression that had defined the administrations of his father Agonglo and grandfather Kpengla, Adandozan tried to reduce slavery to decrease European trade, and when these failed reform the economy to focus on agriculture. Unfortunately, these efforts did not end domestic dissent and in 1818 at the Annual Customs of Dahomey, Ghezo and Francisco Félix de Sousa, a powerful Brazilian slave trader, organized a coup d'état and replaced Adandozan. He was left alive and lived until the 1860s hidden in the palaces while he was largely erased from official royal history.

Ghezo, also spelled Gezo, was King of Dahomey from 1818 until 1858. Ghezo replaced his brother Adandozan as king through a coup with the assistance of the Brazilian slave trader Francisco Félix de Sousa. He ruled over the kingdom during a tumultuous period, punctuated by the British blockade of the ports of Dahomey in order to stop the Atlantic slave trade.

The Annual Customs of Dahomey were the main yearly celebration in the Kingdom of Dahomey, held at the capital, Abomey. These ceremonies were largely started under King Agaja around 1730 and involved significant collection and distribution of gifts and tribute, religious ceremonies involving human sacrifice, military parades, and discussions by dignitaries about the future for the kingdom.

The Fon people, also called Dahomeans, Fon nu or Agadja are a Gbe ethnic group. They are the largest ethnic group in Benin found particularly in its south region; they are also found in southwest Nigeria and Togo. Their total population is estimated to be about 3,500,000 people, and they speak the Fon language, a member of the Gbe languages.

The Dahomey Amazons were a Fon all-female military regiment of the Kingdom of Dahomey that existed from the 17th century until the late 19th century. They were the only female army in modern history. They were named Amazons by Western Europeans who encountered them, due to the story of the female warriors of Amazons in Greek mythology.

Ouidah or Whydah, and known locally as Glexwe, formerly the chief port of the Kingdom of Whydah, is a city on the coast of the Republic of Benin. The commune covers an area of 364 km2 (141 sq mi) and as of 2002 had a population of 76,555 people.

The Oyo Empire was a Yoruba empire in West Africa. It was located in present-day southern Benin and western Nigeria. The empire grew to become the largest Yoruba-speaking state through the organizational and administrative efforts of the Yoruba people, trade, as well as the military use of cavalry. The Oyo Empire was one of the most politically important states in Western Africa from the mid-17th to the late 18th century and held sway not only over most of the other kingdoms in Yorubaland, but also over nearby African states, notably the Fon Kingdom of Dahomey in the modern Republic of Benin on its west.

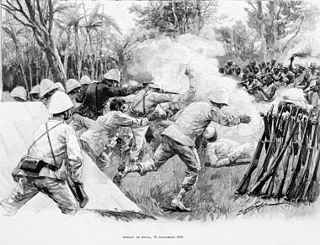

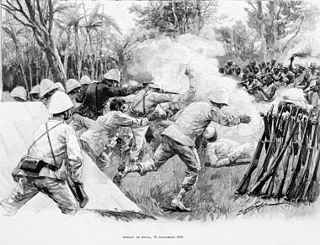

The First Franco-Dahomean War was fought in 1890 between France, led by General Alfred-Amédée Dodds, and Dahomey under King Béhanzin.

The Kingdom of Whydah ( known locally as; Glexwe / Glehoue, but also known and spelt in old literature as; Hueda, Whidah,Ajuda, Ouidah, Whidaw,Juida, and Juda was a kingdom on the coast of West Africa in what is now Benin. It was a major slave trading area which exported more than one million Africans to the United States, the Caribbean and Brazil before closing its trade in the 1860s. In 1700, it had a coastline of around 16 kilometres ; under King Haffon, this was expanded to 64 km, and stretching 40 km inland.

Savi is a town in Benin that was the capital of the Kingdom of Whydah prior to its capture by the forces of Dahomey in 1727.

The Second Franco-Dahomean War, which raged from 1892 to 1894, was a major conflict between France, led by General Alfred-Amédée Dodds, and Dahomey under King Béhanzin. The French emerged triumphant and incorporated Dahomey into their growing colonial territory of French West Africa.

The Royal Palaces of Abomey are 12 palaces spread over an area of 40 hectares at the heart of the Abomey town in Benin, formerly the capital of the West African Kingdom of Dahomey. The Kingdom was founded in 1625 by the Fon people who developed it into a powerful military and commercial empire, which dominated trade with European slave traders on the Slave Coast until the late 19th century, to whom they sold their prisoners of war. At its peak the palaces could accommodate up to 8000 people. The King's palace included a two-story building known as the "cowrie house" or akuehue. Under the twelve kings who succeeded from 1625 to 1900, the kingdom established itself as one of the most powerful of the western coast of Africa.

The History of the Kingdom of Dahomey spans 400 years from around 1600 until 1904 with the rise of the Kingdom of Dahomey as a major power on the Atlantic coast of modern-day Benin until French conquest. The kingdom became a major regional power in the 1720s when it conquered the coastal kingdoms of Allada and Whydah. With control over these key coastal cities, Dahomey became a major center in the Atlantic Slave Trade until 1852 when the British imposed a naval blockade to stop the trade. War with the French began in 1892 and the French took over the Kingdom of Dahomey in 1894. The throne was vacated by the French in 1900, but the royal families and key administrative positions of the administration continued to have a large impact in the politics of the French administration and the post-independence Republic of Dahomey, renamed Benin in 1975. Historiography of the kingdom has had a significant impact on work far beyond African history and the history of the kingdom forms the backdrop for a number of novels and plays.

Hangbe was a woman who served as the regent of the Kingdom of Dahomey for a brief period before Agaja came to power in 1718. According to oral tradition, she became regent upon the sudden death of King Akaba because his oldest son, Agbo Sassa, was not yet of age. The duration of her regency is unclear. She supported Agbo Sassa in a succession struggle against Agaja, who ultimately became king. Hangbe's legacy lives on in oral tradition, but little is known about her rule because it was largely erased from official history. It is possible that her gender and role as a woman in power contributed to her rule being erased from official history.

Panyarring was the practice of seizing and holding persons until the repayment of debt or resolution of a dispute which became a common activity along the Atlantic coast of Africa in the 18th and 19th centuries. The practice developed from pawnship, a common practice in West Africa where members of a family borrowing money would be pledged as collateral to the family providing credit until the repayment of the debt. Panyarring though is different from this practice as it involves the forced seizure of persons when a debt was not repaid.

The Kingdom of Ardra, also known as the Kingdom of Allada, was a coastal West African kingdom in southern Benin. While historically a sovereign kingdom, in present times the monarchy continues to exist as a non-sovereign monarchy within the republic of Benin.