Islamic art is a part of Islamic culture and encompasses the visual arts produced since the 7th century CE by people who lived within territories inhabited or ruled by Muslim populations. Referring to characteristic traditions across a wide range of lands, periods, and genres, Islamic art is a concept used first by Western art historians in the late 19th century. Public Islamic art is traditionally non-representational, except for the widespread use of plant forms, usually in varieties of the spiralling arabesque. These are often combined with Islamic calligraphy, geometric patterns in styles that are typically found in a wide variety of media, from small objects in ceramic or metalwork to large decorative schemes in tiling on the outside and inside of large buildings, including mosques. Other forms of Islamic art include Islamic miniature painting, artefacts like Islamic glass or pottery, and textile arts, such as carpets and embroidery.

Nishapur is a city in the Central District of Nishapur County, Razavi Khorasan Province, Iran, serving as capital of both the county and the district.

Lustreware or lusterware is a type of pottery or porcelain with a metallic glaze that gives the effect of iridescence. It is produced by metallic oxides in an overglaze finish, which is given a second firing at a lower temperature in a "muffle kiln", or a reduction kiln, excluding oxygen.

Kraak ware or Kraak porcelain is a type of Chinese export porcelain produced mainly in the late Ming dynasty, in the Wanli reign (1573–1620), but also in the Tianqi (1620–1627) and the Chongzhen (1627–1644). It was among the first Chinese export wares to arrive in Europe in mass quantities, and was frequently featured in Dutch Golden Age paintings of still life subjects with foreign luxuries.

"Blue and white pottery" covers a wide range of white pottery and porcelain decorated under the glaze with a blue pigment, generally cobalt oxide. The decoration was commonly applied by hand, originally by brush painting, but nowadays by stencilling or by transfer-printing, though other methods of application have also been used. The cobalt pigment is one of the very few that can withstand the highest firing temperatures that are required, in particular for porcelain, which partly accounts for its long-lasting popularity. Historically, many other colours required overglaze decoration and then a second firing at a lower temperature to fix that.

Islamic pottery occupied a geographical position between Chinese ceramics, and the pottery of the Byzantine Empire and Europe. For most of the period, it made great aesthetic achievements and influence as well, influencing Byzantium and Europe. The use of drinking and eating vessels in gold and silver, the ideal in ancient Rome and Persia as well as medieval Christian societies, is prohibited by the Hadiths, with the result that pottery and glass were used for tableware by Muslim elites, as pottery also was in China but was much rarer in Europe and Byzantium. In the same way, Islamic restrictions greatly discouraged figurative wall painting, encouraging the architectural use of schemes of decorative and often geometrically patterned titles, which are the most distinctive and original speciality of Islamic ceramics.

Swatow ware or Zhangzhou ware is a loose grouping of mainly late Ming dynasty Chinese export porcelain wares initially intended for the Southeast Asian market. The traditional name in the West arose because Swatow, or present-day Shantou, was the South Chinese port in Guangdong province from which the wares were thought to have been shipped. The many kilns were probably located all over the coastal region, but mostly near Zhangzhou, Pinghe County, Fujian, where several were excavated in the mid-1990s, which has clarified matters considerably.

Underglaze is a method of decorating pottery in which painted decoration is applied to the surface before it is covered with a transparent ceramic glaze and fired in a kiln. Because the glaze subsequently covers it, such decoration is completely durable, and it also allows the production of pottery with a surface that has a uniform sheen. Underglaze decoration uses pigments derived from oxides which fuse with the glaze when the piece is fired in a kiln. It is also a cheaper method, as only a single firing is needed, whereas overglaze decoration requires a second firing at a lower temperature.

Chinese ceramics are one of the most significant forms of Chinese art and ceramics globally. They range from construction materials such as bricks and tiles, to hand-built pottery vessels fired in bonfires or kilns, to the sophisticated Chinese porcelain wares made for the imperial court and for export.

Jun ware is a type of Chinese pottery, one of the Five Great Kilns of Song dynasty ceramics. Despite its fame, much about Jun ware remains unclear, and the subject of arguments among experts. Several different types of pottery are covered by the term, produced over several centuries and in several places, during the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127), Jin dynasty (1115–1234) and Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), and lasting into the early Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

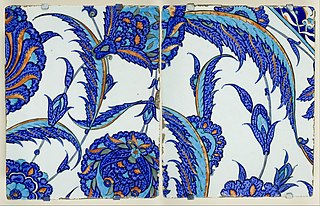

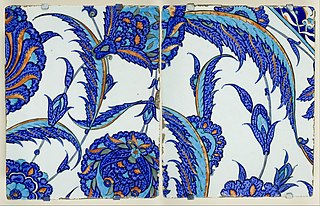

Iznik pottery, or Iznik ware, named after the town of İznik in Anatolia where it was made, is a decorated ceramic that was produced from the last quarter of the 15th century until the end of the 17th century. Turkish stylization is a reflection of Chinese porcelain.

Safavid art is the art of the Iranian Safavid dynasty from 1501 to 1722, encompassing Iran and parts of the Caucasus and Central Asia. It was a high point for Persian miniatures, architecture and also included ceramics, metal, glass, and gardens. The arts of the Safavid period show a far more unitary development than in any other period of Iranian art. The Safavid Empire was one of the most significant ruling dynasties of Iran. They ruled one of the greatest Persian empires since the Muslim conquest of Persia, and with this, the empire produced numerous artistic accomplishments.

Iranian handicrafts are handicraft or handmade crafted works originating from Iran.

Jingdezhen porcelain is Chinese porcelain produced in or near Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province in southern China. Jingdezhen may have produced pottery as early as the sixth century CE, though it is named after the reign name of Emperor Zhenzong, in whose reign it became a major kiln site, around 1004. By the 14th century it had become the largest centre of production of Chinese porcelain, which it has remained, increasing its dominance in subsequent centuries. From the Ming period onwards, official kilns in Jingdezhen were controlled by the emperor, making imperial porcelain in large quantity for the court and the emperor to give as gifts.

Chinese influences on Islamic pottery cover a period starting from at least the 8th century CE to the 19th century. The influence of Chinese ceramics on Islamic pottery has to be viewed in the broader context of the considerable importance of Chinese culture on Islamic arts in general.

Cizhou ware or Tz'u-chou ware is a wide range of Chinese ceramics from between the late Tang dynasty and the early Ming dynasty, but especially associated with the Northern Song to Yuan period in the 11–14th century. It has been increasingly realized that a very large number of sites in northern China produced these wares, and their decoration is very variable, but most characteristically uses black and white, in a variety of techniques. For this reason Cizhou-type is often preferred as a general term. All are stoneware in Western terms, and "high-fired" or porcelain in Chinese terms. They were less high-status than other types such as celadons and Jun ware, and are regarded as "popular", though many are finely and carefully decorated.

Persian pottery or Iranian pottery is the pottery made by the artists of Persia (Iran) and its history goes back to early Neolithic Age. Agriculture gave rise to the baking of clay, and the making of utensils by the people of Iran. Through the centuries, Persian potters have responded to the demands and changes brought by political turmoil by adopting and refining newly introduced forms and blending them into their own culture. This innovative attitude has survived through time and influenced many other cultures around the world.

Persian art or Iranian art has one of the richest art heritages in world history and has been strong in many media including architecture, painting, weaving, pottery, calligraphy, metalworking and sculpture. At different times, influences from the art of neighbouring civilizations have been very important, and latterly Persian art gave and received major influences as part of the wider styles of Islamic art. This article covers the art of Persia up to 1925, and the end of the Qajar dynasty; for later art see Iranian modern and contemporary art, and for traditional crafts see arts of Iran. Rock art in Iran is its most ancient surviving art. Iranian architecture is covered at that article.

Mina'i ware is a type of Persian pottery, or Islamic pottery developed in Kashan in the decades leading up to the Mongol invasion of Persia and Mesopotamia in 1219, after which production ceased. It has been described as "probably the most luxurious of all types of ceramic ware produced in the eastern Islamic lands during the medieval period". The ceramic body of white-ish fritware or stonepaste is fully decorated with detailed paintings using several colours, usually including figures.

The rock and wave design or motif is found painted on the outer borders of some Asian ceramics. It originated in Chinese porcelain of the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) and was later very often used in Iznik pottery and other Turkish ceramics. It represents turbulent waves breaking onto rocks, which are generally depicted as a regular pattern with a considerable degree of stylization, especially in Turkish examples. It is normally in blue and white, even where other parts of the piece use other colours.