Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other raw materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. The place where such wares are made by a potter is also called a pottery. The definition of pottery, used by the ASTM International, is "all fired ceramic wares that contain clay when formed, except technical, structural, and refractory products". End applications include tableware, decorative ware, sanitary ware, and in technology and industry such as electrical insulators and laboratory ware. In art history and archaeology, especially of ancient and prehistoric periods, pottery often means only vessels, and sculpted figurines of the same material are called terracottas.

Delftware or Delft pottery, also known as Delft Blue or as delf, is a general term now used for Dutch tin-glazed earthenware, a form of faience. Most of it is blue and white pottery, and the city of Delft in the Netherlands was the major centre of production, but the term covers wares with other colours, and made elsewhere. It is also used for similar pottery, English delftware.

"Blue and white pottery" covers a wide range of white pottery and porcelain decorated under the glaze with a blue pigment, generally cobalt oxide. The decoration was commonly applied by hand, originally by brush painting, but nowadays by stencilling or by transfer-printing, though other methods of application have also been used. The cobalt pigment is one of the very few that can withstand the highest firing temperatures that are required, in particular for porcelain, which partly accounts for its long-lasting popularity. Historically, many other colours required overglaze decoration and then a second firing at a lower temperature to fix that.

Islamic pottery occupied a geographical position between Chinese ceramics, and the pottery of the Byzantine Empire and Europe. For most of the period, it made great aesthetic achievements and influence as well, influencing Byzantium and Europe. The use of drinking and eating vessels in gold and silver, the ideal in ancient Rome and Persia as well as medieval Christian societies, is prohibited by the Hadiths, with the result that pottery and glass were used for tableware by Muslim elites, as pottery also was in China but was much rarer in Europe and Byzantium. In the same way, Islamic restrictions greatly discouraged figurative wall painting, encouraging the architectural use of schemes of decorative and often geometrically patterned titles, which are the most distinctive and original speciality of Islamic ceramics.

Underglaze is a method of decorating pottery in which painted decoration is applied to the surface before it is covered with a transparent ceramic glaze and fired in a kiln. Because the glaze subsequently covers it, such decoration is completely durable, and it also allows the production of pottery with a surface that has a uniform sheen. Underglaze decoration uses pigments derived from oxides which fuse with the glaze when the piece is fired in a kiln. It is also a cheaper method, as only a single firing is needed, whereas overglaze decoration requires a second firing at a lower temperature.

Tin-glazing is the process of giving tin-glazed pottery items a ceramic glaze that is white, glossy and opaque, which is normally applied to red or buff earthenware. Tin-glaze is plain lead glaze with a small amount of tin oxide added. The opacity and whiteness of tin glaze encourage its frequent decoration. Historically this has mostly been done before the single firing, when the colours blend into the glaze, but since the 17th century also using overglaze enamels, with a light second firing, allowing a wider range of colours. Majolica, maiolica, delftware and faience are among the terms used for common types of tin-glazed pottery.

Egyptian faience is a sintered-quartz ceramic material from Ancient Egypt. The sintering process "covered [the material] with a true vitreous coating" as the quartz underwent vitrification, creating a bright lustre of various colours "usually in a transparent blue or green isotropic glass". Its name in the Ancient Egyptian language was tjehenet, and modern archeological terms for it include sintered quartz, glazed frit, and glazed composition. Tjehenet is distinct from the crystalline pigment Egyptian blue, for which it has sometimes incorrectly been used as a synonym.

Blue pottery is widely recognized as a traditional craft of Jaipur of Central Asian origin. The name 'blue pottery' comes from the eye-catching cobalt blue dye used to colour the pottery. It is one of many Eurasian types of blue and white pottery, and related in the shapes and decoration to Islamic pottery and, more distantly, Chinese pottery.

Ceramic glaze, or simply glaze, is a glassy coating on ceramics. It is used for decoration, to ensure the item is impermeable to liquids and to minimise the adherence of pollutants.

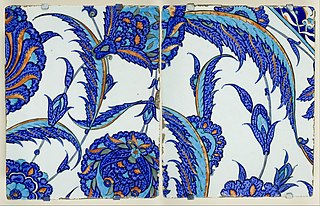

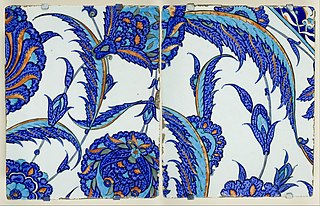

Iznik pottery, or Iznik ware, named after the town of İznik in Anatolia where it was made, is a decorated ceramic that was produced from the last quarter of the 15th century until the end of the 17th century. Turkish stylization is a reflection of Chinese porcelain.

A frit is a ceramic composition that has been fused, quenched, and granulated. Frits form an important part of the batches used in compounding enamels and ceramic glazes; the purpose of this pre-fusion is to render any soluble and/or toxic components insoluble by causing them to combine with silica and other added oxides. However, not all glass that is fused and quenched in water is frit, as this method of cooling down very hot glass is also widely used in glass manufacture.

This is a list of pottery and ceramic terms.

Chinese influences on Islamic pottery cover a period starting from at least the 8th century CE to the 19th century. The influence of Chinese ceramics on Islamic pottery has to be viewed in the broader context of the considerable importance of Chinese culture on Islamic arts in general.

Characterized by lusterware and mina'i techniques, Seljuk pottery was able to accelerate in production, which made way for new designs, motifs, and patterns to emerge.

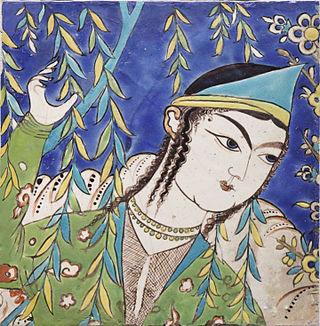

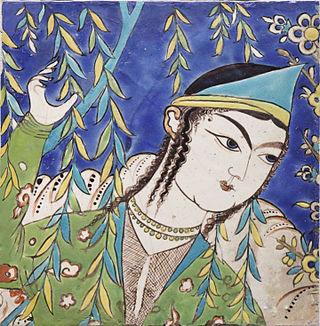

Persian pottery or Iranian pottery is the pottery made by the artists of Persia (Iran) and its history goes back to early Neolithic Age. Agriculture gave rise to the baking of clay, and the making of utensils by the people of Iran. Through the centuries, Persian potters have responded to the demands and changes brought by political turmoil by adopting and refining newly introduced forms and blending them into their own culture. This innovative attitude has survived through time and influenced many other cultures around the world.

Lead-glazed earthenware is one of the traditional types of earthenware with a ceramic glaze, which coats the ceramic bisque body and renders it impervious to liquids, as terracotta itself is not. Plain lead glaze is shiny and transparent after firing. Coloured lead glazes are shiny and either translucent or opaque after firing. Three other traditional techniques are tin-glazed, which coats the ware with an opaque white glaze suited for overglaze brush-painted colored enamel designs; salt glaze pottery, also often stoneware; and the feldspathic glazes of Asian porcelain. Modern materials technology has invented new glazes that do not fall into these traditional categories.

Cuerda seca is a technique used when applying coloured glazes to ceramic surfaces.

Ceramic art is art made from ceramic materials, including clay. It may take varied forms, including artistic pottery, including tableware, tiles, figurines and other sculpture. As one of the plastic arts, ceramic art is a visual art. While some ceramics are considered fine art, such as pottery or sculpture, most are considered to be decorative, industrial or applied art objects. Ceramic art can be created by one person or by a group, in a pottery or a ceramic factory with a group designing and manufacturing the artware.

Kubachi ware is a style of Persian pottery. Though it takes its name from the town of Kubachi in Dagestan, modern-day Russia, scholars believe that Kubachi ware pieces were created during the Safavid Period in the northwestern part of what is now Iran. Nishapur, Tabriz, Mashhad, and Isfahan have all been put forth as possible places of origin for Kubachi ware.

Lajvardina-type ceramics were developed in the 13th century following the Mongol invasion of Persia. It was produced throughout the Ilkhanate reign. It is characterized by its deep blue color and often features geometric patterns or foliage inlaid with gold leaf. The style was created using overglaze enamel. An initial layer of dark blue glaze, produced from cobalt, was applied, followed by another layer, often gold, on which the details were painted. It was primarily produced in Kashan, a center for ceramic production and lusterware in the 12th and early 13th centuries. The style was continuously used for tiles and ornamental objects from the 1260s C.E. until the mid-14th century, when production dropped significantly, coinciding with the fall of the Ilkhanate in 1335.