Kurds or Kurdish people are an Iranic ethnic group native to the mountainous region of Kurdistan in Western Asia, which spans southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northern Syria. There are exclaves of Kurds in Central Anatolia, Khorasan, and the Caucasus, as well as significant Kurdish diaspora communities in the cities of western Turkey and Western Europe. The Kurdish population is estimated to be between 30 and 45 million.

The Kurds are an Iranian ethnic group in the Middle East. They have historically inhabited the mountainous areas to the south of Lake Van and Lake Urmia, a geographical area collectively referred to as Kurdistan. Most Kurds speak Northern Kurdish Kurmanji Kurdish (Kurmanji) and Central Kurdish (Sorani).

The music of Armenia has its origins in the Armenian highlands, dating back to the 3rd millennium BCE, and is a long-standing musical tradition that encompasses diverse secular and religious, or sacred, music. Folk music was notably collected and transcribed by Komitas Vardapet, a prominent composer and musicologist, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, who is also considered the founder of the modern Armenian national school of music. Armenian music has been presented internationally by numerous artists, such as composers Aram Khachaturian, Alexander Arutiunian, Arno Babajanian, Haig Gudenian, and Karen Kavaleryan as well as by traditional performers such as duduk player Djivan Gasparyan.

The music of Iran encompasses music that is produced by Iranian artists. In addition to the traditional folk and classical genres, it also includes pop and internationally celebrated styles such as jazz, rock, and hip hop.

Sephardic music is an umbrella term used to refer to the music of the Sephardic Jewish community. Sephardic Jews have a diverse repertoire the origins of which center primarily around the Mediterranean basin. In the secular tradition, material is usually sung in dialects of Judeo-Spanish, though other languages including Hebrew, Turkish, Greek, and other local languages of the Sephardic diaspora are widely used. Sephardim maintain geographically unique liturgical and para-liturgical traditions.

Iraqi Kurdistan or Southern Kurdistan refers to the Kurdish-populated part of northern Iraq. It is considered one of the four parts of "Kurdistan" in Western Asia, which also includes parts of southeastern Turkey, northern Syria, and northwestern Iran. Much of the geographical and cultural region of Iraqi Kurdistan is part of the Kurdistan Region (KRI), an autonomous region recognized by the Constitution of Iraq. As with the rest of Kurdistan, and unlike most of the rest of Iraq, the region is inland and mountainous.

Soghomon Soghomonian, ordained and commonly known as Komitas, was an Armenian priest, musicologist, composer, arranger, singer, and choirmaster, who is considered the founder of the Armenian national school of music. He is recognized as one of the pioneers of ethnomusicology.

The Kurdish languages are written in either of two alphabets: a Latin alphabet introduced by Celadet Alî Bedirxan in 1932 called the Bedirxan alphabet or Hawar alphabet and an Arabic script called the Sorani or Central Kurdish alphabet. The Kurdistan Region has agreed upon a standard for Central Kurdish, implemented in Unicode for computation purposes.

Kurmanji, also termed Northern Kurdish, is the northernmost of the Kurdish languages, spoken predominantly in southeast Turkey, northwest and northeast Iran, northern Iraq, northern Syria and the Caucasus and Khorasan regions. It is the most widely spoken form of Kurdish.

Newroz or Nawroz is the Kurdish celebration of Nowruz; the arrival of spring and new year in Kurdish culture. The lighting of the fires at the beginning of the evening of March 20 is the main symbol of Newroz among the Kurds.

Dildar, born Yûnis Reûf was a Kurdish poet and political activist, best known for writing the Kurdish national anthem Ey Reqîb.

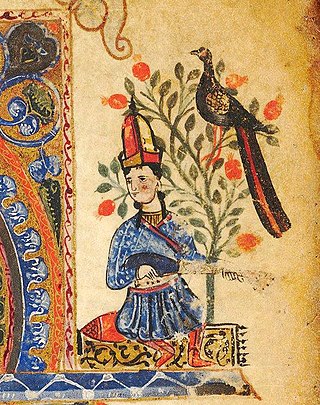

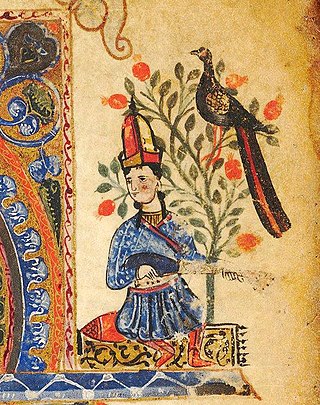

Kurdish literature is literature written in the Kurdish languages. Literary Kurdish works have been written in each of the four main languages: Zaza, Gorani, Kurmanji and Sorani. Ali Hariri (1009–1079) is one of the first well-known poets who wrote in Kurdish. He was from the Hakkari region.

Doğubayazıt is a town of Ağrı Province of Turkey, near the border with Iran. Its elevation is 1625 m. It is the seat of Doğubayazıt District. Its population is 80,061 (2021). Also known as Kurdava, the town was the capital of the self-declared Republic of Ararat, an independent Kurdish state centered in the Ağrı Province.

Ali Hariri or Sheikh Ahmed Bohtani was a Kurdish poet who wrote in Kurmanji and considered a pioneer in classical Kurdish Sufi literature and a founder of the Kurdish literary tradition.

Kurds have had a long history of discrimination perpetrated against them by the Turkish government. Massacres have periodically occurred against the Kurds since the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923. Among the most significant is the massacre that happened during the Dersim rebellion, when 13,160 civilians were killed by the Turkish Army and 11,818 people were sent into exile. According to McDowall, 40,000 people were killed. The Zilan massacre of 1930 was a massacre of Kurdish residents of Turkey during the Ararat rebellion, in which 5,000 to 47,000 were killed.

Iranian folk music refers to the folk music transmitted through generations among the people of Iran, often consisting of tunes that exist in numerous variants.

Karapetê Xaço or Karabêtê Xaço or Gerabêtê Xaço, was an Armenian singer of traditional Kurdish Dengbêj music.

Garnik Serobi Asatrian is an Iranian-born Armenian professor who studies and teaches Kurdish culture at Yerevan State University in Yerevan, Armenia.

"Kurdish melodies" is a collection of Kurdish folk songs collected and transcribed by Armenian composer Komitas during field work among Kurds and published in December 1903. Despite collecting a large amount of Kurdish melodies, most of them were lost, and Kurdish melodies became the only publication of Kurdish songs by Komitas. Kurdish melodies would consequently become the first publication of Kurdish music.