Kurdish people or Kurds are an Iranic ethnic group native to the mountainous region of Kurdistan in Western Asia, which spans southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northern Syria. There are exclaves of Kurds in Central Anatolia, Khorasan, and the Caucasus, as well as significant Kurdish diaspora communities in the cities of western Turkey and Western Europe. The Kurdish population is estimated to be between 30 and 45 million.

Kurdistan Region is an autonomous administrative entity within the Republic of Iraq. It comprises four Kurdish-majority divisions of Arab-majority Iraq: the Erbil Governorate, the Sulaymaniyah Governorate, the Duhok Governorate, and Halabja Governorate. The KRI is bordered by Iran to the east, by Turkey to the north, and by Syria to the west. It does not govern all of Iraqi Kurdistan, and lays claim to the disputed territories of northern Iraq; these territories have a predominantly non-Arab population and were subject to the Ba'athist Arabization campaigns throughout the late 20th century. Though the KRI's autonomy was realized in 1992, one year after Iraq's defeat in the Gulf War, these northern territories remain contested between the Kurdistan Regional Government and the Government of Iraq to the present day. In light of the dispute, the KRI's constitution declares the city of Kirkuk as the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan. However, the KRI does not control Kirkuk, and the Kurdistan Region Parliament is based in Erbil. In 2014, when the Syria-based Islamic State began their Northern Iraq offensive and invaded the country, the Iraqi Armed Forces retreated from most of the disputed territories. The KRI's Peshmerga then entered and took control of them for the duration of the War in Iraq (2013–2017). In October 2017, following the defeat of the Islamic State, the Iraqi Armed Forces attacked the Peshmerga and reasserted control over the disputed territories.

The Kurdish population is estimated to be between 30 and 45 million. Most Kurdish people live in Kurdistan, which today is split between Iranian Kurdistan, Iraqi Kurdistan, Turkish Kurdistan, and Syrian Kurdistan.

Minorities in Iraq include various ethnic and religious groups.

Kurdification is a cultural change in which people, territory, or language become Kurdish. This can happen both naturally or as a deliberate government policy.

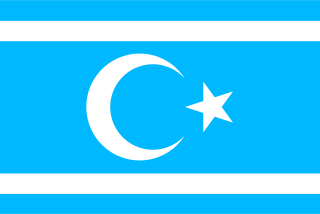

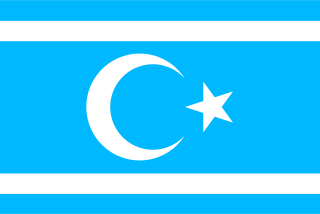

The Iraqi Turkmen, also referred to as Iraqi Turks, Turkish-Iraqis, the Turkish minority in Iraq, and the Iraqi-Turkish minority are Iraq's third largest ethnic group. They make up to 10%–13% of the Iraqi population and are native to northern Iraq. Iraqi Turkmen share ties with Turkish people, and do not identify with the Turkmen of Turkmenistan and Central Asia.

Iraqi Armenians are Iraqi citizens and residents of Armenian ethnicity. Many Armenians settled in Iraq after fleeing the 1915 Armenian genocide. It is estimated that there are 10,000–20,000 Armenians living in Iraq, with communities in Baghdad, Mosul, Basra, Kirkuk, Baqubah, Dohuk, Zakho and Avzrog.

The 1991 Iraqi uprisings were ethnic and religious uprisings against Saddam Hussein's regime in Iraq that were led by Shi'ites and Kurds. The uprisings lasted from March to April 1991 after a ceasefire following the end of the Gulf War. The mostly uncoordinated insurgency was fueled by the perception that Iraqi President Saddam Hussein had become vulnerable to regime change. This perception of weakness was largely the result of the outcome of the Iran–Iraq War and the Gulf War, both of which occurred within a single decade and devastated the population and economy of Iraq.

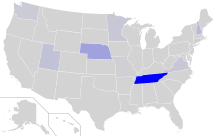

Iraqi Americans are American citizens of Iraqi descent. As of 2015, the number of Iraqi Americans is around 145,279, according to the United States Census Bureau.

Refugees of Iraq are Iraqi nationals who have fled Iraq due to war or persecution. In 1980- 2017, large number of refugees fled Iraq, peaking with the Iraq War and continuing until the end of the War in Iraq (2013–2017). Precipitated by a series of conflicts including the Kurdish rebellions during the Iran–Iraq War, Iraq's Invasion of Kuwait (1990) and the Gulf War (1991), the subsequent sanctions against Iraq (1991–2003), culminating in the Iraq War and the subsequent War in Iraq (2013–2017), millions were forced by insecurity to flee their homes in Iraq. Iraqi refugees established themselves in urban areas in other countries rather than refugee camps.

Kurdish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which asserts that Kurds are a nation and espouses the creation of an independent Kurdistan from Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey.

The Iraqi Kurdish Civil War was a civil war that took place between rival Kurdish factions in Iraqi Kurdistan during the mid-1990s, mostly between the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan and the Kurdistan Democratic Party. Over the course of the conflict, Kurdish factions from Iran and Turkey, as well as Iranian, Iraqi and Turkish forces, were drawn into the fighting, with additional involvement from American forces. Between 35,000 and 40,000 fighters and civilians were killed.

Iraqi nationalism is a form of nationalism that asserts the belief that Iraqis form a nation and promotes the cultural unity of Iraqis of different ethnoreligious groups such as Mesopotamian Arabs, Kurds, Turkmens, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Yazidis, Mandeans, Shabaks and Yarsans.

Kurds in Germany are residents or citizens of Germany of full or partial Kurdish origin. There is a large Kurdish community in Germany. The number of Kurds living in Germany is unknown. Many estimates assume that the number is in the million range. In February 2000, the Federal Government of Germany estimated that approximately 500,000 Kurds lived in Germany at that time.

The Iraqi–Kurdish conflict consists of a series of wars, rebellions and disputes by the Kurds against the central authority of Iraq starting in the 20th century shortly after the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I. Some put the marking point of the conflict beginning to the attempt by Mahmud Barzanji to establish an independent Kingdom of Kurdistan, while others relate to the conflict as only the post-1961 insurrection by the Barzanis. Since the US-led invasion of Iraq and the subsequent adoption of federalism and the recognition of the Kurdistan Region (KRI) as a federal entity in the new Iraqi constitution, the number and scope of armed clashes between the central government of Iraq and the Kurds have significantly decreased. In spite of that, however, there are still outstanding issues that continue to cause strife such as the disputed territories of northern Iraq and rights to export oil and gas, leading to occasional disputes and armed clashes. In September 2023, following a series of punitive measures by the central government in Iraq against KRI, Masrour Barzani sent a letter to the President of the United States expressing concerns about a possible collapse of the Kurdistan Region, and calling for the United States to intervene.

The problem of Kurdish refugees and displaced people arose in the 20th century in the Middle East, and continues today. The Kurds, are an ethnic group in Western Asia, mostly inhabiting a region known as Kurdistan, which includes adjacent parts of Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey.

The Iraqi Kurds are the second largest ethnic group of Iraq. They traditionally speak Kurdish languages of Sorani, Kurmanji, Feyli and also Gorani.

Syrian Kurdistan is a region in northern Syria where Kurds form the majority. It is surrounding three noncontiguous enclaves along the Turkish and Iraqi borders: Afrin in the northwest, Kobani in the north, and Jazira in the northeast. Syrian Kurdistan is often called Western Kurdistan or Rojava, one of the four "Lesser Kurdistans" that comprise "Greater Kurdistan", alongside Iranian Kurdistan, Turkish Kurdistan, and Iraqi Kurdistan.

Anti-Kurdish sentiment, also known as anti-Kurdism or Kurdophobia, is hostility, fear, intolerance or racism against the Kurdish people, Kurdistan, Kurdish culture, or Kurdish languages. A person who holds such positions is sometimes referred to as a "Kurdophobe".

The single largest community in the United States of ethnic Kurds exists is in Nashville, Tennessee. This enclave is often called "Little Kurdistan" and is located in South Nashville. The majority of Nashville's "Little Kurdistan" comes from Iraqi Kurdistan, however there are sizeable communities of Kurds from Syria, Iran, and Turkey. It has been estimated that there are 15,000 Kurds living in Nashville, although more recent estimates place the number at around 20,000, the largest in the country.