North Carolina is currently divided into 14 congressional districts, each represented by a member of the United States House of Representatives. After the 2000 census, the number of North Carolina's seats was increased from 12 to 13 due to the state's increase in population. In the 2022 elections, per the 2020 United States census, North Carolina gained one new congressional seat for a total of 14.

The 2003 Texas redistricting was a controversial intercensus state plan that defined new congressional districts. In the 2004 elections, this redistricting supported the Republicans taking a majority of Texas's federal House seats for the first time since Reconstruction. Democrats in both houses of the Texas Legislature staged walkouts, unsuccessfully trying to prevent the changes. Opponents challenged the plan in three suits, combined when the case went to the United States Supreme Court in League of United Latin American Citizens v. Perry (2006).

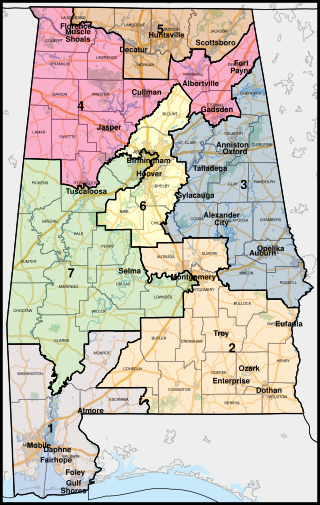

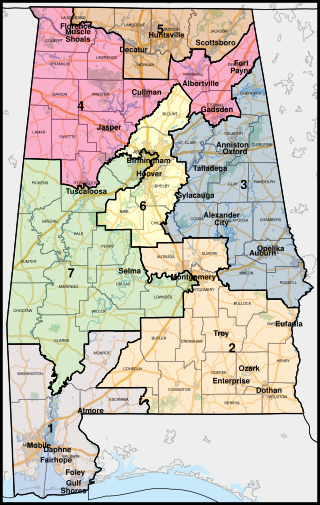

The U.S. state of Alabama is currently divided into seven congressional districts, each represented by a member of the United States House of Representatives.

Vieth v. Jubelirer, 541 U.S. 267 (2004), was a United States Supreme Court ruling that was significant in the area of partisan redistricting and political gerrymandering. The court, in a plurality opinion by Justice Antonin Scalia and joined by Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justices Sandra Day O'Connor and Clarence Thomas, with Justice Anthony Kennedy concurring in the judgment, upheld the ruling of the District Court in favor of the appellees that the alleged political gerrymandering was not unconstitutional. Subsequent to the ruling, partisan bias in redistricting increased dramatically in the 2010 redistricting round.

Davis v. Federal Election Commission, 554 U.S. 724 (2008), is a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States which held that section 319 of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 unconstitutionally infringed on candidates' rights as provided by First Amendment.

Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109 (1986), is a case in which the United States Supreme Court held that claims of partisan gerrymandering were justiciable, but failed to agree on a clear standard for the judicial review of the class of claims of a political nature to which such cases belong. The decision was later limited with respect to many of the elements directly involving issues of redistricting and political gerrymandering, but was somewhat broadened with respect to less significant ancillary procedural issues. Democrats had won 51.9% of the votes, but only 43/100 seats. Democrats sued on basis of one man, one vote, however, California Democrats supported the Indiana GOP's plan.

Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952 (1996), is a United States Supreme Court case concerning racial gerrymandering, where racial minority majority-electoral districts were created during Texas' 1990 redistricting to increase minority Congressional representation. The Supreme Court, in a plurality opinion, held that race was the predominant factor in the creation of the districts and that under a strict scrutiny standard the three districts were not narrowly tailored to further a compelling governmental interest.

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986), was a United States Supreme Court case in which a unanimous Court found that "the legacy of official discrimination ... acted in concert with the multimember districting scheme to impair the ability of "cohesive groups of black voters to participate equally in the political process and to elect candidates of their choice." The ruling resulted in the invalidation of districts in the North Carolina General Assembly and led to more single-member districts in state legislatures.

Gerrymandering is the practice of setting boundaries of electoral districts to favor specific political interests within legislative bodies, often resulting in districts with convoluted, winding boundaries rather than compact areas. The term "gerrymandering" was coined after a review of Massachusetts's redistricting maps of 1812 set by Governor Elbridge Gerry noted that one of the districts looked like a mythical salamander.

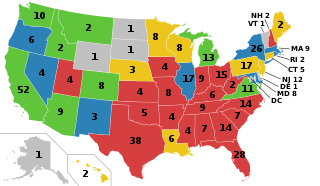

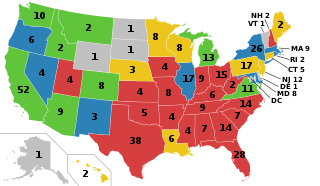

The 2020 United States redistricting cycle is in progress following the completion of the 2020 United States census. In all fifty states, various bodies are re-drawing state legislative districts. States that are apportioned more than one seat in the United States House of Representatives are also drawing new districts for that legislative body.

Gill v. Whitford, 585 U.S. ___ (2018), was a United States Supreme Court case involving the constitutionality of partisan gerrymandering. Other forms of gerrymandering based on racial or ethnic grounds had been deemed unconstitutional, and while the Supreme Court had identified that extreme partisan gerrymandering could also be unconstitutional, the Court had not agreed on how this could be defined, leaving the question to lower courts to decide. That issue was later resolved in Rucho v. Common Cause, in which the Court decided that partisan gerrymanders presented a nonjusticiable political question.

Benisek v. Lamone, 585 U.S. ____ (2018), and Lamone v. Benisek, 588 U.S. ____ (2019), were a pair of decisions by the Supreme Court of the United States in a case dealing with the topic of partisan gerrymandering arising from the 2011 Democratic party-favored redistricting of Maryland. At the center of the cases was Maryland's 6th district which historically favored Republicans and which was redrawn in 2011 to shift the political majority to become Democratic via vote dilution. Affected voters filed suit, stating that the redistricting violated their right of representation under Article One, Section Two of the U.S. Constitution and freedom of association of the First Amendment.

Abbott v. Perez, 585 U.S. ___ (2018), was a United States Supreme Court case dealing with the redistricting of the state of Texas following the 2010 census.

Rucho v. Common Cause, No. 18-422, 588 U.S. ___ (2019) is a landmark case of the United States Supreme Court concerning partisan gerrymandering. The Court ruled that while partisan gerrymandering may be "incompatible with democratic principles", the federal courts cannot review such allegations, as they present nonjusticiable political questions outside the remit of these courts.

Redistricting in North Carolina has been a controversial topic due to allegations and admissions of gerrymandering.

Virginia House of Delegates v. Bethune-Hill, 587 U.S. ___ (2019), was a case argued before the United States Supreme Court on March 18, 2019, in which the Virginia House of Delegates appealed against the decision in 2018 by the district court that 11 of Virginia's voting districts were racially gerrymandered, and thus unconstitutional. The Court held the "Virginia House of Delegates lacks standing to file this appeal, either representing the state's interests or in its own right." In other words, the court upheld the decision made by a federal district court ruling in June 2018 that 11 state legislative districts were an illegal racial gerrymander. This was following a previous (2017) case, Bethune-Hill v. Virginia State Bd. of Elections.

Redistricting in Wisconsin is the process by which boundaries are redrawn for municipal wards, Wisconsin State Assembly districts, Wisconsin State Senate districts, and Wisconsin's congressional districts. Redistricting typically occurs—as in other U.S. states—once every decade, usually in the year after the decennial United States census. According to the Wisconsin Constitution, redistricting in Wisconsin follows the regular legislative process, it must be passed by both houses of the Wisconsin Legislature and signed by the Governor of Wisconsin—unless the Legislature has sufficient votes to override a gubernatorial veto. Due to political gridlock, however, it has become common for Wisconsin redistricting to be conducted by courts. The 1982, 1992, and 2002 legislative maps were each created by panels of United States federal judges.

Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, 594 U.S. ___ (2021), was a United States Supreme Court case related to voting rights established by the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA), and specifically the applicability of Section 2's general provision barring discrimination against minorities in state and local election laws in the wake of the 2013 Supreme Court decision Shelby County v. Holder, which removed the preclearance requirements for election laws for certain states that had been set by Sections 4(b) and 5. Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee involves two of Arizona's election policies: one outlawing ballot collection and another banning out-of-precinct voting. The Supreme Court ruled in a 6–3 decision in July 2021 that neither of Arizona's election policies violated the VRA or had a racially discriminatory purpose.

Allen v. Milligan, 599 U. S. 1 (2023), is a landmark United States Supreme Court case related to redistricting under the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA). The appellees and respondants argued that Alabama's congressional districts discriminated against African-American voters. The Court ruled 5–4 that Alabama’s districts likely violated the VRA, maintained an injunction that required Alabama to create an additional majority-minority district, and held that Section 2 of the VRA is constitutional in the redistricting context.

Moore v. Harper, 600 U.S. 1 (2023), is a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States related to independent state legislature theory (ISL), a doctrine that asserts state legislatures have sole authority to establish election laws for federal elections within their respective states without judicial review by state courts, presentment to state governors, and without constraint by state constitutions. The case arose from the redistricting of North Carolina's districts by its legislature after the 2020 United States census, which the state courts found to be too artificial and partisan, and an extreme case of gerrymandering in favor of the Republican Party.