The Underground Railroad was a network of secret routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and from there to Canada. The network, primarily the work of free African Americans, was assisted by abolitionists and others sympathetic to the cause of the escapees. The slaves who risked capture and those who aided them are also collectively referred to as the passengers and conductors of the "Underground Railroad". Various other routes led to Mexico, where slavery had been abolished, and to islands in the Caribbean that were not part of the slave trade. An earlier escape route running south toward Florida, then a Spanish possession, existed from the late 17th century until approximately 1790. However, the network now generally known as the Underground Railroad began in the late 18th century. It ran north and grew steadily until the Emancipation Proclamation was signed by President Abraham Lincoln. One estimate suggests that, by 1850, approximately 100,000 slaves had escaped to freedom via the network.

William Still was an African-American abolitionist based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was a conductor of the Underground Railroad and was responsible for aiding and assisting at least 649 slaves to freedom towards North. Still was also a businessman, writer, historian and civil rights activist. Before the American Civil War, Still was chairman of the Vigilance Committee of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, named the Vigilant Association of Philadelphia. He directly aided fugitive slaves and also kept records of the people served in order to help families reunite.

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th centuries to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called freedom seekers to avoid implying that the enslaved person had committed a crime and that the slaveholder was the injured party.

Calvin Fairbank was an American abolitionist and Methodist minister from New York state who was twice convicted in Kentucky of aiding the escape of slaves, and served a total of 19 years in the Kentucky State Penitentiary in Frankfort. Fairbank is believed to have aided the escape of 47 slaves.

Thomas Garrett was an American abolitionist and leader in the Underground Railroad movement before the American Civil War. He helped more than 2,500 African Americans escape slavery.

The Boston African American National Historic Site, in the heart of Boston, Massachusetts's Beacon Hill neighborhood, interprets 15 pre-Civil War structures relating to the history of Boston's 19th-century African-American community, connected by the Black Heritage Trail. These include the 1806 African Meeting House, the oldest standing black church in the United States.

Lewis Hayden escaped slavery in Kentucky with his family and escaped to Canada. He established a school for African Americans before moving to Boston, Massachusetts to aid in the abolition movement. There he became an abolitionist, lecturer, businessman, and politician. Before the American Civil War, he and his wife Harriet Hayden aided numerous fugitive slaves on the Underground Railroad, often sheltering them at their house.

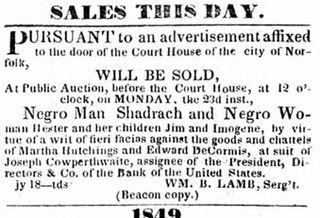

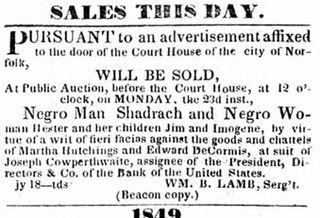

Shadrach Minkins was an African-American fugitive slave from Virginia who escaped in 1850 and reached Boston. He also used the pseudonyms Frederick Wilkins and Frederick Jenkins. He is known for being freed from a courtroom in Boston after being captured by United States marshals under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Members of the Boston Vigilance Committee freed and hid him, helping him get to Canada via the Underground Railroad. Minkins settled in Montreal, where he raised a family. Two men were prosecuted in Boston for helping free him, but they were acquitted by the jury.

The Boston Vigilance Committee (1841–1861) was an abolitionist organization formed in Boston, Massachusetts, to protect escaped slaves from being kidnapped and returned to slavery in the South. The Committee aided hundreds of escapees, most of whom arrived as stowaways on coastal trading vessels and stayed a short time before moving on to Canada or England. Notably, members of the Committee provided legal and other aid to George Latimer, Ellen and William Craft, Shadrach Minkins, Thomas Sims, and Anthony Burns.

The William C. Nell House, now a private residence, was a boarding home located in 3 Smith Court in the Beacon Hill neighbourhood of Boston, Massachusetts, opposite the former African Meeting House, now the Museum of African American History.

The Underground Railroad in Indiana was part of a larger, unofficial, and loosely-connected network of groups and individuals who aided and facilitated the escape of runaway slaves from the southern United States. The network in Indiana gradually evolved in the 1830s and 1840s, reached its peak during the 1850s, and continued until slavery was abolished throughout the United States at the end of the American Civil War in 1865. It is not known how many fugitive slaves escaped through Indiana on their journey to Michigan and Canada. An unknown number of Indiana's abolitionists, anti-slavery advocates, and people of color, as well as Quakers and other religious groups illegally operated stations along the network. Some of the network's operatives have been identified, including Levi Coffin, the best-known of Indiana's Underground Railroad leaders. In addition to shelter, network agents provided food, guidance, and, in some cases, transportation to aid the runaways.

The Stephen and Harriet Myers Residence is located on Livingston Avenue in Albany, New York, United States. It is a Greek Revival townhouse built in the mid-19th century. In 2004, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It is also listed on the New York State Underground Railroad Heritage Trail and is a site on the National Park Service's National Network to Freedom.

John J. Smith House was the home of John J. Smith from 1878 to 1893. Smith was an African American abolitionist, Underground Railroad contributor and politician, including three terms as a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives. He also played a key role in rescuing Shadrach Minkins from federal custody, along with Lewis Hayden and others.

John James Smith was a barber shop owner, abolitionist, a three-term Massachusetts state representative, and one of the first African-American members of the Boston Common Council. A Republican, he served three terms in the Massachusetts House of Representatives. He was born in Richmond Virginia. He took part in the California Gold Rush.

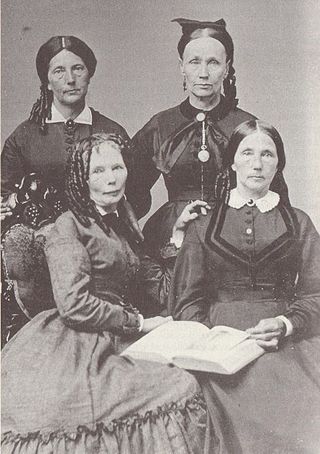

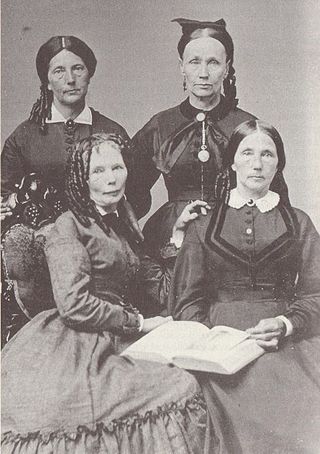

Delia Ann Webster was an American teacher, author, businesswoman and abolitionist in Kentucky who, with Calvin Fairbank, aided many slaves, including Lewis Hayden, his wife Harriet, and their son Joseph to escape to Ohio. She was convicted and sentenced to two years in the Kentucky State Penitentiary in Frankfort for aiding the Haydens' escape, but pardoned after two months.

The Twelfth Baptist Church is a historic church in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts. Established in 1840, it is the oldest direct descendant of the First Independent Baptist Church in Beacon Hill. Notable members have included abolitionists such as Lewis Hayden and Rev. Leonard Grimes, the historian George Washington Williams, the artist Edward Mitchell Bannister, abolitionist and entrepreneur Christiana Carteaux, pioneering educator Wilhelmina Crosson, and civil rights movement leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Austin Bearse (1808-1881) was a sea captain from Cape Cod who provided transportation for fugitive slaves in the years leading up to the American Civil War.

Harriet Bell Hayden (1816-1893) was an African-American antislavery activist in Boston, Massachusetts. She and her husband, Louis Hayden, were the primary operators of the Underground Railroad in Boston and also aided the John Brown slave revolt conspiracy.

Elizabeth Cook Riley was an African-American Bostonian abolitionist who aided in the escape of fugitive slave Shadrach Minkins. She was a member of the committee which raised the first funds towards William Lloyd Garrison's The Liberator, a prominent antislavery newspaper. Afterwards, she was active in the Boston abolitionist community, helping to organize meetings and events.