Related Research Articles

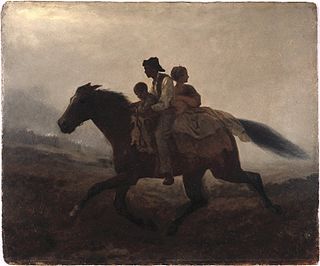

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to the mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. The network was assisted by abolitionists and others sympathetic to the cause of the escapees. The enslaved persons who risked escape and those who aided them are also collectively referred to as the "Underground Railroad". Various other routes led to Mexico, where slavery had been abolished, and to islands in the Caribbean that were not part of the slave trade. An earlier escape route running south toward Florida, then a Spanish possession, existed from the late 17th century until approximately 1790. However, the network now generally known as the Underground Railroad began in the late 18th century. It ran north and grew steadily until the Emancipation Proclamation was signed by President Abraham Lincoln. One estimate suggests that by 1850, approximately 100,000 enslaved people had escaped to freedom via the network.

Cass County is a county in the U.S. state of Michigan. As of the 2020 Census, the population was 51,589. Its county seat is Cassopolis.

Porter Township is a civil township of Cass County in the U.S. state of Michigan. The population was 3,798 at the 2010 census.

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was passed by the United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern Free-Soilers.

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th century to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called freedom seekers to avoid implying that the slave had committed a crime and that the slaveholder was the injured party.

Erastus Hussey (1800–1889) was a leading abolitionist, a stationmaster on the Underground Railroad, and one of the founders of the Republican Party. He supported himself and his family as a farmer, teacher, businessman, legislator, and editor.

Samuel D. Burris was a member of the Underground Railroad. He had a family, who he moved to Philadelphia for safety and traveled into Maryland and Delaware to guide freedom seekers north along the Underground Railroad to Pennsylvania.

Henry Walton Bibb was an American author and abolitionist who was born a slave. Bibb told his life story in his narrative The Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb: An American Slave, which included many failed escape attempts followed finally by success when he escaped to Detroit. After leaving Detroit to move to Canada with his family, due to issues with the legality of his assistance in the Underground Railroad, he founded the abolitionist newspaper, Voice of the Fugitive. He lived in Canada until his death.

The history of slavery in Kentucky dates from the earliest permanent European settlements in the state, until the end of the Civil War. Kentucky was classified as the Upper South or a border state, and enslaved African Americans represented 24% by 1830, but declined to 19.5% by 1860 on the eve of the Civil War. The majority of enslaved people in Kentucky were concentrated in the cities of Louisville and Lexington, in the fertile Bluegrass Region as well the Jackson Purchase, both the largest hemp- and tobacco-producing areas in the state. In addition, many enslaved people lived in the Ohio River counties where they were most often used in skilled trades or as house servants. Few people lived in slavery in the mountainous regions of eastern and southeastern Kentucky. Those that did that were held in eastern and southeastern Kentucky served primarily as artisans and service workers in towns.

The Underground Railroad in Indiana was part of a larger, unofficial, and loosely-connected network of groups and individuals who aided and facilitated the escape of runaway slaves from the southern United States. The network in Indiana gradually evolved in the 1830s and 1840s, reached its peak during the 1850s, and continued until slavery was abolished throughout the United States at the end of the American Civil War in 1865. It is not known how many fugitive slaves escaped through Indiana on their journey to Michigan and Canada. An unknown number of Indiana's abolitionists, anti-slavery advocates, and people of color, as well as Quakers and other religious groups illegally operated stations along the network. Some of the network's operatives have been identified, including Levi Coffin, the best-known of Indiana's Underground Railroad leaders. In addition to shelter, network agents provided food, guidance, and, in some cases, transportation to aid the runaways.

William Parker was an American former slave who escaped from Maryland to Pennsylvania, where he became an abolitionist and anti-slavery activist in Christiana. He was a farmer and led a black self-defense organization. He was notable as a principal figure in the Christiana incident, 1851, also known as the Christiana Resistance. Edward Gorsuch, a Maryland slaveowner who owned four slaves who had fled over the state border to Parker's farm, was killed and other white men in the party to capture the fugitives were wounded. The events brought national attention to the challenges of enforcing the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.

History of slavery in Michigan includes the pro-slavery and anti-slavery efforts of the state's residents prior to the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1865.

George DeBaptiste was a prominent African-American conductor on the Underground Railroad in southern Indiana and Detroit, Michigan. Born free in Virginia, he moved as a young man to the free state of Indiana. In 1840, he served as valet and then White House steward for US President William Henry Harrison, who was from that state. In the 1830s and 1840s DeBaptiste was an active conductor in Madison, Indiana. Located along the Ohio River across from Kentucky, a slave state, this town was a destination for refugee slaves seeking escape from slavery.

Black Canadians migrated north in the 18th and 19th centuries from the United States, many of them through the Underground Railroad, into Southwestern Ontario, Toronto, and Owen Sound. Black Canadians fought in the War of 1812 and Rebellions of 1837–1838 for the British. Some returned to the United States during the American Civil War or during the Reconstruction era.

Emeline and Samuel Hawkins were a couple from Queen Anne's County, Maryland who had six children together and ran away from Emeline and her children's slaveholders in 1845, with the assistance of Samuel Burris, a conductor on the Underground Railroad. They made it through a winter snowstorm to John Hunn's farm, where they were captured and placed in the New Castle jail. Thomas Garrett interceded and as a result the Hawkins were freed and they settled in Byberry, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Two slaveholders, Charles Glanding and Elizabeth Turner, claimed to own Emeline and her six children. Glanding and Turner initiated lawsuits against Hunn and Garrett. Found guilty by a jury primarily made up of slaveholders, Hunn and Garrett were financially devastated by the fines levied against them.

Wright Modlin or Wright Maudlin (1797–1866) helped enslaved people escape slavery, whether transporting them between Underground Railroad stations or traveling south to find people that he could deliver directly to Michigan. Modlin and his Underground Railroad partner, William Holden Jones, traveled to the Ohio River and into Kentucky to assist enslave people on their journey north. Due to their success, angry slaveholders instigated the Kentucky raid on Cass County of 1847. Two years later, he helped free his neighbors, the David and Lucy Powell family, who had been captured by their former slaveholder. Tried in South Bend, Indiana, the case was called The South Bend Fugitive Slave Case.

Adam Crosswhite (1799–1878) was a formerly enslaved man who fled slavery along the Underground Railroad and settled in Marshall, Michigan. In 1847, slaveholders and slave catchers from Kentucky came to Michigan to retrieve African Americans and return them to slavery. Citizens of the town surrounded the Crosswhite's house and prevented them from being abducted. The Crosswhites fled to Canada and their former owner Francis Giltner filed a suit, Giltner vs. Gorham et. al., against residents of Marshall. Giltner won the case and was compensated for the loss of the Crosswhite family. After the Civil War, Crosswhite returned to Marshall, where he lived out the rest of his life.

Guy Beckley (1803–1847) was a Methodist Episcopal minister, abolitionist, Underground Railroad stationmaster, and lecturer. The Guy Beckley House is on the National Park Service Underground Railroad Network to Freedom and the Journey to Freedom tour. It stands next to Beckley Park, which was named after him.

The Signal of Liberty was an anti-slavery newspaper published in the mid-19th century in Michigan. The decision to publish a newspaper was one of the outcomes of the founding meeting of the Michigan Anti-Slavery Society that met for several days beginning on November 10, 1836 in Ann Arbor of the Michigan Territory (1805–1837). In 1838, Nicholas and William Sullivan published Michigan's first antislavery newspaper, the American Freedmen in Jackson, Michigan. Seymour Treadwell published and was the editor of the Michigan Freeman in 1839. The papers did not have a regular printing schedule.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Eby, John (2005-06-17). "State Bar memorializing 1847 slave raid 'milestone'". Dowagiac Daily News. Cassopolis. Retrieved 2022-02-27– via Leader Publications.

- ↑ Rogers 1875, p. 131.

- ↑ "Erastus Hussey: Stationmaster / 'Working for Humanity' Historical Marker". www.hmdb.org. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ↑ "Historical Marker - S637 - Erastus Hussey: Stationmaster / "Working for Humanity" (Marker ID#:S637)" (PDF). Department of Natural Resources, Michigan. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ↑ Heinecke, Rhoda L. [from old catalog (1961). Michigan. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. p. 18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "1847 Kentucky Raid". Underground Railroad Society of Cass County. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- 1 2 "1847 Kentucky Raid: The Underground Railroad and Fugitive Slave Law in Cass County, Michigan". Clio. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ↑ "UGRR Site Driving Tour". Underground Railroad Society of Cass County. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ↑ Rogers 1875, p. 129.

- ↑ "Legislator Details - Erastus Hussey". mdoe.state.mi.us. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ↑ "1849-Sampson Sanders Frees all 51 of his Slaves". Clio. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ↑ "'Kentucky Raid' film discussed". South Bend Tribune. Retrieved 2022-02-27.