In Greek mythology, Lethe, also referred to as Lesmosyne, was one of the rivers of the underworld of Hades. Also known as the Amelēs potamos, the Lethe flowed around the cave of Hypnos and through the Underworld where all those who drank from it experienced complete forgetfulness. Lethe was also the name of the Greek spirit of forgetfulness and oblivion, with whom the river was often identified.

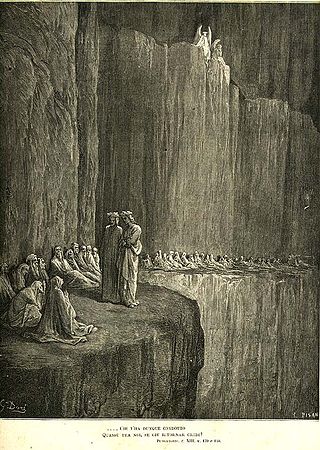

The Divine Comedy is an Italian narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun c. 1308 and completed around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature and one of the greatest works of Western literature. The poem's imaginative vision of the afterlife is representative of the medieval worldview as it existed in the Western Church by the 14th century. It helped establish the Tuscan language, in which it is written, as the standardized Italian language. It is divided into three parts: Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso.

Publius Papinius Statius was a Latin poet of the 1st century CE. His surviving poetry includes an epic in twelve books, the Thebaid; a collection of occasional poetry, the Silvae; and an unfinished epic, the Achilleid. He is also known for his appearance as a guide in the Purgatory section of Dante's epic poem, the Divine Comedy.

Purgatorio is the second part of Dante's Divine Comedy, following the Inferno and preceding the Paradiso. The poem was written in the early 14th century. It is an allegory telling of the climb of Dante up the Mount of Purgatory, guided by the Roman poet Virgil – except for the last four cantos, at which point Beatrice takes over as Dante's guide. Allegorically, Purgatorio represents the penitent Christian life. In describing the climb Dante discusses the nature of sin, examples of vice and virtue, as well as moral issues in politics and in the Church. The poem posits the theory that all sins arise from love – either perverted love directed towards others' harm, or deficient love, or the disordered or excessive love of good things.

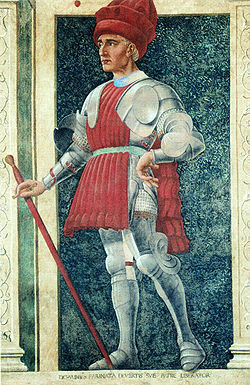

Ripheus was a Trojan hero and the name of a figure from the Aeneid of Virgil. A comrade of Aeneas, he was a Trojan who was killed defending his city against the Greeks. "Ripheus also fell," Virgil writes, "uniquely the most just of all the Trojans, the most faithful preserver of equity; but the gods decided otherwise". Ripheus's righteousness was not rewarded by the gods.

Iacopo Rusticucci was a Guelph politician and accomplished orator who lived and worked in Florence, Italy in the 13th century. Rusticucci is realized historically primarily in relation to the Adimari family, who wielded much power and prestige in thirteenth-century Florence, and to whom it is thought Rusticucci was a close companion, representative, and perhaps lawyer. Despite his association with men born into high political and social rank, Rusticucci was not born into nobility, and nothing is known of his ancestors or predecessors. The exact dates of his birth and death are unknown.

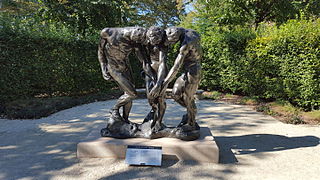

Eunoe is a feature of Dante's Divine Comedy created by Dante as the fifth river of the dead. In the Purgatorio, the second cantica of Dante's poem, penitents reaching the Garden of Eden at the top of Mount Purgatory are first washed in the waters of the river Lethe in order to forget the memories of their mortal sins. They then pass through Eunoe to have the memories of their good deeds in life strengthened.

Gualdrada Berti dei Ravignani was a member of the Ghibelline nobility of twelfth-century Florence, Italy. A descendant of the Ravignani family and daughter of the powerful Bellincione Berti, Gualdrada later married into the Conti Guido family. Her character as a pure and virtuous Florentine woman is called upon by many late medieval Italian authors, including Dante Alighieri, Giovanni Boccaccio, and Giovanni Villani.

Forese Donati was an Italian nobleman born in Florence, associated with the Guelphs. He was the son of Simone di Forese and Tessa, and the brother of Corso and Piccarda Donati. He was married to Nella Donati, and had one daughter, Ghita, with her. He was known as a childhood friend of Dante Alighieri. He died in 1296, in Firenze.

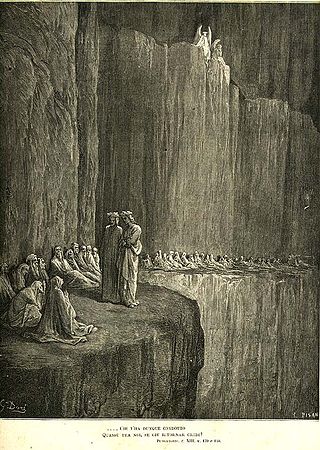

Inferno is the first part of Italian writer Dante Alighieri's 14th-century epic poem Divine Comedy. It is followed by Purgatorio and Paradiso. The Inferno describes the journey of a fictionalised version of Dante himself through Hell, guided by the ancient Roman poet Virgil. In the poem, Hell is depicted as nine concentric circles of torment located within the Earth; it is the "realm ... of those who have rejected spiritual values by yielding to bestial appetites or violence, or by perverting their human intellect to fraud or malice against their fellowmen". As an allegory, the Divine Comedy represents the journey of the soul toward God, with the Inferno describing the recognition and rejection of sin.

Paradiso is the third and final part of Dante's Divine Comedy, following the Inferno and the Purgatorio. It is an allegory telling of Dante's journey through Heaven, guided by Beatrice, who symbolises theology. In the poem, Paradise is depicted as a series of concentric spheres surrounding the Earth, consisting of the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, the Fixed Stars, the Primum Mobile and finally, the Empyrean. It was written in the early 14th century. Allegorically, the poem represents the soul's ascent to God.

Dante's Inferno: An Animated Epic is a 2010 American-Korean-Japanese adult animated dark fantasy film. Based on the Dante's Inferno video game that is itself loosely based on Dante's Inferno, Dante must travel through the circles of Hell and battle demons, creatures, monsters, and even Lucifer himself to save his beloved Beatrice. The film was released on February 9, 2010.

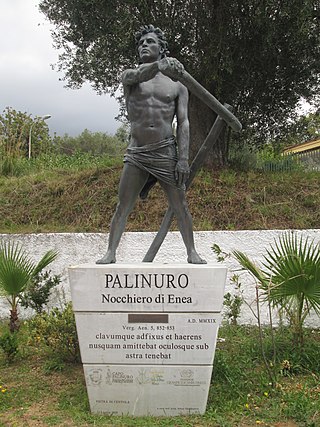

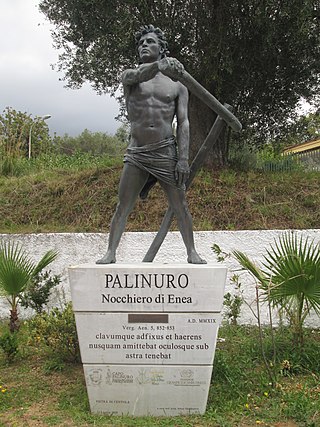

Palinurus (Palinūrus), in Roman mythology and especially Virgil's Aeneid, is the coxswain of Aeneas' ship. Later authors used him as a general type of navigator or guide. Palinurus is an example of human sacrifice; his life is the price for the Trojans landing in Italy.

Guido Guerra V (1220-1272) was a politician from Florence, Italy. Aligned with the Guelph faction, Guerra had a prominent role in the political conflicts of mid-thirteenth century Tuscany. He was admired by Dante Alighieri, who granted him honor in the Divine Comedy, even though he placed Guerra in Hell among sinners of sodomy.

Matelda, anglicized as Matilda in some translations, is a minor character in Dante Alighieri's Purgatorio, the second canticle of the Divine Comedy. She is present in the final six cantos of the canticle, but is unnamed until Canto XXXIII. While Dante makes Matelda's function as a baptizer in the Earthly Paradise clear, commentators have disagreed about what historical figure she is intended to represent, if any.

Bonconte I da Montefeltro was an Italian Ghibelline general. He led Ghibelline forces in several engagements until his battlefield death. Dante Alighieri featured Montefeltro as a character in the Divine Comedy.

Sapia Salvani was a Sienese noblewoman. In Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, she is placed among the envious souls of Purgatory for having rejoiced when her fellow Sienese townspeople, led by her nephew Provenzano Salvani, lost to the Florentine Guelphs at the Battle of Colle Val d'Elsa.

The first circle of hell is depicted in Dante Alighieri's 14th-century poem Inferno, the first part of the Divine Comedy. Inferno tells the story of Dante's journey through a vision of hell ordered into nine circles corresponding to classifications of sin. The first circle is Limbo, the space reserved for those souls who died before baptism and for those who hail from non-Christian cultures. They live eternally in a castle set on a verdant landscape, but forever removed from heaven.

The second circle of hell is depicted in Dante Alighieri's 14th-century poem Inferno, the first part of the Divine Comedy. Inferno tells the story of Dante's journey through a vision of the Christian hell ordered into nine circles corresponding to classifications of sin; the second circle represents the sin of lust, where the lustful are punished by being buffeted within an endless tempest.

The third circle of hell is depicted in Dante Alighieri's Inferno, the first part of the 14th-century poem Divine Comedy. Inferno tells the story of Dante's journey through a vision of the Christian hell ordered into nine circles corresponding to classifications of sin; the third circle represents the sin of gluttony, where the souls of the gluttonous are punished in a realm of icy mud.