Mayan or Maya mythology is part in of Mesoamerican mythology and comprises all of the Maya tales in which personified forces of nature, deities, and the heroes interacting with these play the main roles. The legends of the era have to be reconstructed from iconography. Other parts of Mayan oral tradition are not considered here.

Yama is the Hindu deity of death, dharma, the south direction, and the underworld. Belonging to an early stratum of Rigvedic Hindu deities, Yama is said to have been the first mortal who died in the Vedas. By virtue of precedence, he became the ruler of the departed.

Matsya is the fish avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu. Often described as the first of Vishnu's ten primary avatars, Matsya is described to have rescued the first man, Manu, from a great deluge. Matsya may be depicted as a giant fish, often golden in color, or anthropomorphically with the torso of Vishnu connected to the rear half of a fish.

Chinese mythology is mythology that has been passed down in oral form or recorded in literature throughout the area now known as Greater China. Chinese mythology encompasses a diverse array of myths derived from regional and cultural traditions. Populated with engaging narratives featuring extraordinary individuals and beings endowed with magical powers, these stories often unfold in fantastical mythological realms or historical epochs. Similar to numerous other mythologies, Chinese mythology has historically been regarded, at least partially, as a factual record of the past.

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas comprise numerous different cultures. Each has its own mythologies, many of which share certain themes across cultural boundaries. In North American mythologies, common themes include a close relation to nature and animals as well as belief in a Great Spirit that is conceived of in various ways.

Japanese mythology is a collection of traditional stories, folktales, and beliefs that emerged in the islands of the Japanese archipelago. Shinto traditions are the cornerstones of Japanese mythology. The history of thousands of years of contact with Chinese and various Indian myths are also key influences in Japanese religious belief.

A flood myth or a deluge myth is a myth in which a great flood, usually sent by a deity or deities, destroys civilization, often in an act of divine retribution. Parallels are often drawn between the flood waters of these myths and the primeval waters which appear in certain creation myths, as the flood waters are described as a measure for the cleansing of humanity, in preparation for rebirth. Most flood myths also contain a culture hero, who "represents the human craving for life".

Hayagriva is a Hindu deity, the horse-headed avatar of Vishnu. The purpose of this incarnation was to slay a danava also named Hayagriva, who had the neck of a horse and the body of a human.

Jamshid also known as Yima is the fourth Shah of the mythological Pishdadian dynasty of Iran according to Shahnameh.

Philippine mythology is rooted in the many indigenous Philippine folk religions. Philippine mythology exhibits influence from Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist, and Christian traditions.

The Fifth World in the context of creation myths describes the present world as interpreted by several indigenous groups in the USA and Mexico. The central theme of the myth holds that there were four other cycles of creation and destruction that preceded the Fifth World. The creation story is taken largely from the mythological, cosmological, and eschatological beliefs and traditions of earlier Mesoamerican cultures.

The Epic of Darkness is a collection of tales and legends of primeval China in epic poetry, preserved by the inhabitants of the Shennongjia mountain area in Hubei. It is composed of numerous Chinese myths relating to the creation of the world, containing accounts from the birth of Pangu till the historical era. It dates back to the Tang dynasty of China. It was translated and published by Hu Chongjun after the discovery of a manuscript in 1982.

Many references to ravens exist in world lore and literature. Most depictions allude to the appearance and behavior of the wide-ranging common raven. Because of its black plumage, croaking call, and diet of carrion, the raven is often associated with loss and ill omen. Yet, its symbolism is complex. As a talking bird, the raven also represents prophecy and insight. Ravens in stories often act as psychopomps, connecting the material world with the world of spirits.

Turtles are frequently depicted in popular culture as easygoing, patient, and wise creatures. Due to their long lifespan, slow movement, sturdiness, and wrinkled appearance, they are an emblem of longevity and stability in many cultures around the world. Turtles are regularly incorporated into human culture, with painters, photographers, poets, songwriters, and sculptors using them as subjects. They have an important role in mythologies around the world, and are often implicated in creation myths regarding the origin of the Earth. Sea turtles are a charismatic megafauna and are used as symbols of the marine environment and environmentalism.

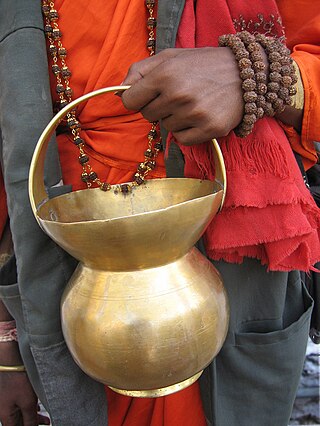

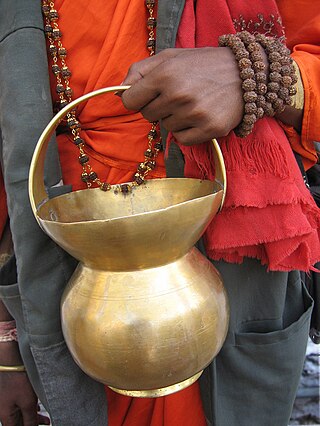

Kamandalu, kamandal, or kamandalam is an oblong water pot, originating from the Indian subcontinent, made of a dry gourd (pumpkin) or coconut shell, metal, wood of the Kamandalataru tree, or from clay, usually with a handle and sometimes with a spout. Hindu ascetics or yogis often use it for storing drinking water. The water-filled kamandalu, which is invariably carried by ascetics, is stated to represent a simple and self-contained life.

There are a vast array of myths surrounding the Blackfoot Native Americans as well as Aboriginal people. The Blackfeet inhabit the Great Plains, in the areas known as Alberta, Saskatchewan, and areas of Montana. These stories, myths, origins, and legends play a big role in their everyday life, such as their religion, their history, and their beliefs. Only the elders of the Blackfoot tribes are allowed to tell the tales, and are typically difficult to obtain because the elders of the tribes are often reluctant to tell them to strangers who are not of the tribe. People such as George B. Grinnell, John Maclean, D.C. Duvall, Clark Wissler, and James Willard Schultz were able to obtain and record a number of the stories that are told by the tribes.

Inca mythology is the universe of legends and collective memory of the Inca civilization, which took place in the current territories of Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina, incorporating in the first instance, systematically, the territories of the central highlands of Peru to the north.

Vietnamese mythology comprises folklore, national myths, legends, or fairy tales from the Vietnamese people with aspects of folk religion in Vietnam. Vietnamese folklore and oral traditions may have also been influenced by historical contact with neighbouring Tai-speaking populations, other Austroasiatic-speaking peoples, as well as with people from the region now known as Greater China.

The Indo-European cosmogony refers to the creation myth of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European mythology.