Animation is a filmmaking technique by which still images are manipulated to create moving images. In traditional animation, images are drawn or painted by hand on transparent celluloid sheets (cels) to be photographed and exhibited on film. Animation has been recognized as an artistic medium, specifically within the entertainment industry. Many animations are computer animations made with computer-generated imagery (CGI). Stop motion animation, in particular claymation, has continued to exist alongside these other forms.

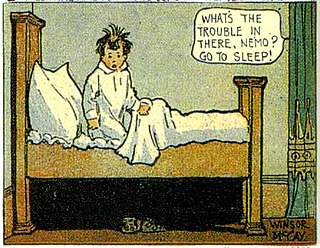

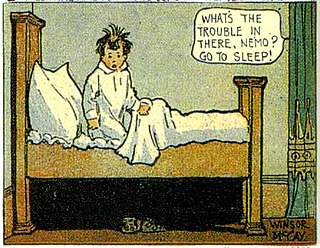

Little Nemo is a fictional character created by American cartoonist Winsor McCay. He originated in an early comic strip by McCay, Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, before receiving his own spin-off series, Little Nemo in Slumberland. The full-page weekly strip depicted Nemo having fantastic dreams that were interrupted by his awakening in the final panel. The strip is considered McCay's masterpiece for its experiments with the form of the comics page, its use of color and perspective, its timing and pacing, the size and shape of its panels, and its architectural and other details.

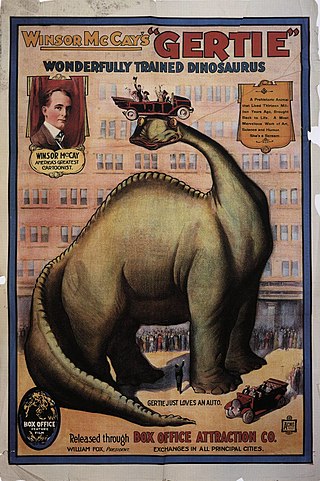

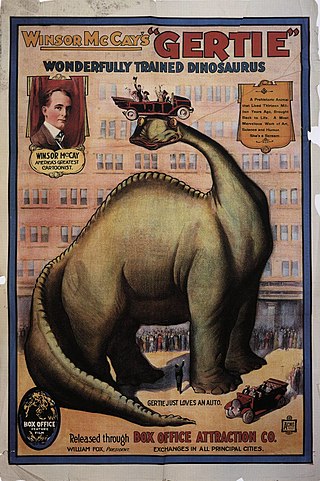

Gertie the Dinosaur is a 1914 animated short film by American cartoonist and animator Winsor McCay. It is the earliest animated film to feature a dinosaur. McCay first used the film before live audiences as an interactive part of his vaudeville act; the frisky, childlike Gertie did tricks at the command of her master. McCay's employer William Randolph Hearst curtailed McCay's vaudeville activities, so McCay added a live-action introductory sequence to the film for its theatrical release renamed Winsor McCay, the Famous Cartoonist, and Gertie. McCay abandoned a sequel, Gertie on Tour, after producing about a minute of footage.

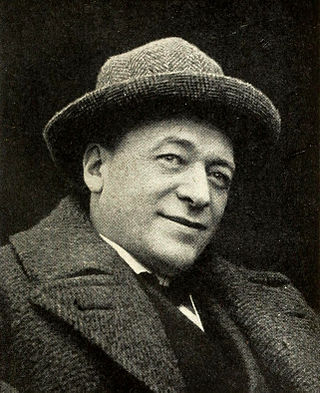

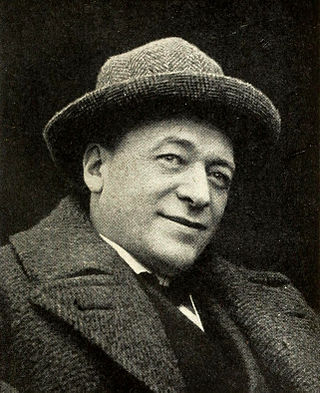

Zenas Winsor McCay was an American cartoonist and animator. He is best known for the comic strip Little Nemo and the animated film Gertie the Dinosaur (1914). For contractual reasons, he worked under the pen name Silas on the comic strip Dream of the Rarebit Fiend.

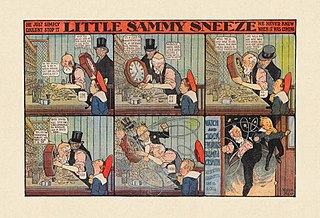

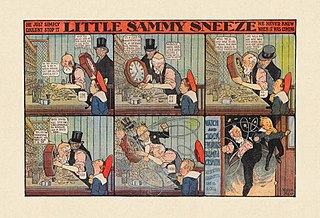

Dream of the Rarebit Fiend is a newspaper comic strip by American cartoonist Winsor McCay, begun September 10, 1904. It was McCay's second successful strip, after Little Sammy Sneeze secured him a position on the cartoon staff of the New York Herald. Rarebit Fiend appeared in the Evening Telegram, a newspaper published by the Herald. For contractual reasons, McCay signed the strip with the pen name "Silas".

Émile Eugène Jean Louis Cohl was a French caricaturist of the Incoherent Movement, cartoonist, and animator, called "The Father of the Animated Cartoon".

The silent age of American animation dates back to at least 1906 when Vitagraph released Humorous Phases of Funny Faces. Although early animations were rudimentary, they rapidly became more sophisticated with such classics as Gertie the Dinosaur in 1914, Felix the Cat, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, and Koko the Clown.

John Cannizzaro Jr., better known as John Canemaker, is an American independent animator, animation historian, author, teacher and lecturer. In 1980, he began teaching and developing the animation program at New York University, Tisch School of the Arts', Kanbar Institute of Film and Television Department. Since 1988 he has directed the program and is currently a tenured full professor. From 2001-2002 he was Acting Chair of the NYU Undergraduate Film and Television Department. In 2006, his film The Moon and the Son: An Imagined Conversation, a 28-minute animated piece about Canemaker's relationship with his father, won the Academy Award for best animated short. In 2007 the same piece picked up an Emmy award for its graphic and artistic design.

Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland is a 1989 animated musical fantasy film directed by Masami Hata and William Hurtz. Based on the comic strip Little Nemo in Slumberland by Winsor McCay, the film went through a lengthy development process with a number of screenwriters. Ultimately, the screenplay was credited to Chris Columbus and Richard Outten; the storyline and art style differed from the original version. The original soundtrack was penned by the Academy Award-winning Sherman Brothers. The film features the English dub voices of Gabriel Damon, Mickey Rooney, René Auberjonois, Danny Mann, and Bernard Erhard.

Scott Bukatman is a cultural theorist and Professor of Film and Media Studies at Stanford University. Bukatman's research examines how popular media and genres "mediate between new technologies and human perceptual and bodily experience."

The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918) is an American silent animated short film by cartoonist Winsor McCay. It is a work of propaganda re-creating the never-photographed 1915 sinking of the British liner RMS Lusitania. At twelve minutes, it has been called the longest work of animation at the time of its release. The film is the earliest surviving animated documentary and serious, dramatic work of animation. The National Film Registry selected it for preservation in 2017.

John Randolph Bray was an American animator, cartoonist, and film producer.

Professor Genius is a character, who originated in the comic strip Little Nemo in Slumberland by Winsor McCay and other subsequent media. He is the right-hand man to King Morpheus, the ruler of Slumberland. His main jobs are to look after the Princess, Little Nemo, and make sure the King's things are in order.

How a Mosquito Operates is a 1912 silent animated film by American cartoonist Winsor McCay. The six-minute short depicts a giant mosquito tormenting a sleeping man. The film is one of the earliest works of animation, and its technical quality is considered far ahead of its time. It is also known under the titles The Story of a Mosquito and Winsor McCay and his Jersey Skeeters.

A chalk talk is an illustrated performance in which the speaker draws pictures to emphasize lecture points and create a memorable and entertaining experience for listeners. Chalk talks differ from other types of illustrated talks in their use of real-time illustration rather than static images. They achieved great popularity during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, appearing in vaudeville shows, Chautauqua assemblies, religious rallies, and smaller venues. Since their inception, chalk talks have been both a popular form of entertainment and a pedagogical tool.

Robert Winsor McCay was an American cartoonist during the golden age of comic books. He worked professionally under the names R. Winsor McCay, Winsor McCay Jr., and Bob McCay. He was the son of cartoonist and animator Winsor McCay.

Disney's Nine Old Men were a group of Walt Disney Productions' core animators, who worked at the studio from the 1920s to the 1980s. Some of the Nine Old Men also worked as directors, creating some of Disney's most popular animated movies from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to The Rescuers. The group was named by Walt Disney himself, and they worked in both short and feature films. Disney delegated more and more tasks to them in the animation department in the 1950s when their interests expanded, and diversified their scope. Eric Larson was the last to retire from Disney, after his role as animation consultant on The Great Mouse Detective in 1986. All nine members of the group were acknowledged as Disney Legends in 1989 and all would receive the Winsor McCay Award for their lifetime or career contributions to the art of animation.

Little Sammy Sneeze was a comic strip by American cartoonist Winsor McCay. In each episode the titular Sammy sneezed himself into an awkward or disastrous predicament. The strip ran from July 24, 1904 until December 9, 1906 in the New York Herald, where McCay was on the staff. It was McCay's first successful comic strip; he followed it with Dream of the Rarebit Fiend later in 1904, and his best-known strip Little Nemo in Slumberland in 1905.

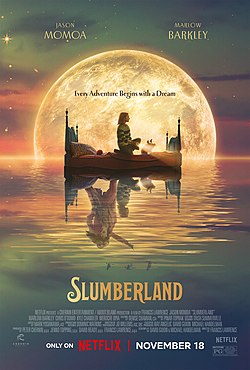

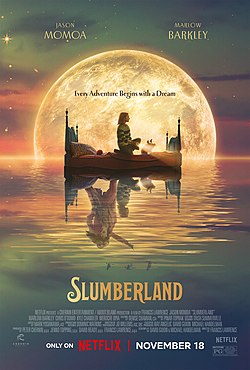

Slumberland is a 2022 American fantasy adventure film directed by Francis Lawrence and written by David Guion and Michael Handelman. Based on the comic strip Little Nemo in Slumberland by Winsor McCay, the film stars Jason Momoa, Chris O'Dowd, Kyle Chandler, Weruche Opia, and introducing Marlow Barkley in her film debut as Nemo. It tells the story of a young girl who goes to live with her uncle after her father is lost at sea and enters Slumberland where she befriends a renegade character who is involved in a plot to get to the Sea of Nightmares and obtain a special pearl that may have the power to reunite her with her father.

Events in 1896 in animation.