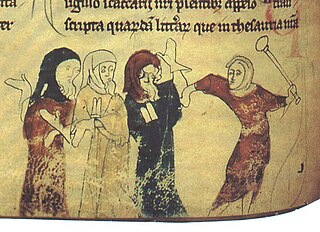

Blood libel or ritual murder libel is an antisemitic canard which falsely accuses Jews of murdering Christians in order to use their blood in the performance of religious rituals. Echoing very old myths of secret cultic practices in many prehistoric societies, the claim, as it is leveled against Jews, was rarely attested to in antiquity. According to Tertullian, it originally emerged in late antiquity as an accusation made against members of the early Christian community of the Roman Empire. Once this accusation had been dismissed, it was revived a millennium later as a Christian slander against Jews in the medieval period. The first examples of medieval blood libel emerged in England in the mid 1100s before spreading into other parts of Europe, especially France and Germany. This libel, alongside those of well poisoning and host desecration, became a major theme of the persecution of Jews in Europe from that period down to modern times.

Edward I, also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he was Lord of Ireland, and from 1254 to 1306 he ruled Gascony as Duke of Aquitaine in his capacity as a vassal of the French king. Before his accession to the throne, he was commonly referred to as the Lord Edward. The eldest son of Henry III, Edward was involved from an early age in the political intrigues of his father's reign. In 1259, he briefly sided with a baronial reform movement, supporting the Provisions of Oxford. After reconciliation with his father, he remained loyal throughout the subsequent armed conflict, known as the Second Barons' War. After the Battle of Lewes, Edward was held hostage by the rebellious barons, but escaped after a few months and defeated the baronial leader Simon de Montfort at the Battle of Evesham in 1265. Within two years, the rebellion was extinguished and, with England pacified, Edward left to join the Ninth Crusade to the Holy Land in 1270. He was on his way home in 1272 when he was informed of his father's death. Making a slow return, he reached England in 1274 and was crowned at Westminster Abbey.

Henry III, also known as Henry of Winchester, was King of England, Lord of Ireland, and Duke of Aquitaine from 1216 until his death in 1272. The son of King John and Isabella of Angoulême, Henry assumed the throne when he was only nine in the middle of the First Barons' War. Cardinal Guala Bicchieri declared the war against the rebel barons to be a religious crusade and Henry's forces, led by William Marshal, defeated the rebels at the battles of Lincoln and Sandwich in 1217. Henry promised to abide by Great Charter of 1225, a later version of the 1215 Magna Carta, which limited royal power and protected the rights of the major barons. His early rule was dominated first by Hubert de Burgh and then Peter des Roches, who re-established royal authority after the war. In 1230, the King attempted to reconquer the provinces of France that had once belonged to his father, but the invasion was a debacle. A revolt led by William Marshal's son Richard broke out in 1232, ending in a peace settlement negotiated by the Church.

Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, later sometimes referred to as Simon V de Montfort to distinguish him from his namesake relatives, was an English nobleman of French origin and a member of the English peerage, who led the baronial opposition to the rule of King Henry III of England, culminating in the Second Barons' War. Following his initial victories over royal forces, he became de facto ruler of the country, and played a major role in the constitutional development of England.

Dominguito del Val was a legendary child in medieval Spain, allegedly a choirboy ritually murdered by Jews in Zaragoza (Saragossa). Dominguito is the protagonist of the first blood libel in the history of Spain – stories that grew in prominence in the 12th and 13th centuries of the Middle Ages, and contributed to antisemitic incidents. According to the legend, Dominguito was ritually murdered by Jews of Zaragoza.

William of Norwich was an apprentice who lived in the English city of Norwich. He suffered a violent death during Easter 1144. The city's French-speaking Jewish community was blamed for his death, but the crime was never solved.

The Edict of Expulsion was a royal decree issued by Edward I on 18 July 1290 expelling all Jews from the Kingdom of England, the first time a European state is known to have permanently banned their presence. The date was most likely chosen as it was a Jewish holy day, the ninth of Ab, commemorating the destruction of Jerusalem and other disasters that the Jewish people have experienced. Edward told the sheriffs of all counties that he wanted all Jews expelled before All Saints' Day that year.

The first Jews in England arrived after the Norman Conquest of the country by William the Conqueror in 1066, and the first written record of Jewish settlement in England dates from 1070. Jews suffered massacres in 1189–90, and after a period of rising persecution, all Jews were expelled from England after the Edict of Expulsion in 1290.

Sir John Lexington was a baron and royal official in 13th century England. He has been described as having been Lord Chancellor, but other scholars believe he merely held the royal seals while the office was vacant or the chancellor was abroad. He served two terms, once from 1247 to 1248, and again from 1249 to 1250.

History of European Jews in the Middle Ages covers Jewish history in the period from the 5th to the 15th century. During the course of this period, the Jewish population experienced a gradual diaspora shifting from their motherland of the Levant to Europe. These Jewish individuals settled primarily in the regions of Central Europe dominated by the Holy Roman Empire and Southern Europe dominated by various Iberian kingdoms. As with Christianity, the Middle Ages were a period in which Judaism became mostly overshadowed by Islam in the Middle East, and an increasingly influential part of the socio-cultural and intellectual landscape of Europe.

Eleanor of Castile was Queen of England as the first wife of Edward I. She was educated at the Castilian court. She also ruled as Countess of Ponthieu in her own right from 1279. After intense diplomatic manoeuvres to secure her marriage to affirm English sovereignty over Gascony, she was married to Prince Edward at the monastery of Las Huelgas, Burgos, on 1 November 1254, at 13. She is believed to have had a child not long after.

Thomas of Monmouth was a Benedictine monk who lived in the Priory at Norwich Cathedral, England during the mid-twelfth century. He was the author of The Life and Miracles of St William of Norwich, a hagiography of William of Norwich that is considered the earliest example of the ritual murder libel.

Antisemitism in the history of the Jews in the Middle Ages became increasingly prevalent in the Late Middle Ages. Early instances of pogroms against Jews are recorded in the context of the First Crusade. Expulsions of Jews from cities and instances of blood libel became increasingly common from the 13th to the 15th century. This trend only peaked after the end of the medieval period, and it only subsided with Jewish emancipation in the late 18th and 19th centuries.

Ariel Toaff is a professor of Medieval and Renaissance History at Bar-Ilan University in Israel, whose work has focused on Jews and their history in Italy.

"Sir Hugh", also known as "The Jew's Daughter" or "The Jew's Garden", is a traditional British folk song, Child ballad No. 155, Roud No. 73, a folkloric example of a blood libel. The original texts are not preserved, but the versions written down from the 18th century onwards show a clear relationship with the 1255 accusations of the murder of Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln by Jews in Lincoln, making it likely that the known versions derive from compositions made around that time.

The Statute of Jewry was a statute issued by Henry III of England in 1253. In response to widespread anti-Jewish sentiment, Henry attempted to segregate and debase England's Jews with oppressive laws which included imposing the wearing of a yellow Jewish badge to invite the Christian public's disdain.

Saint Robert of Bury was an English boy, allegedly murdered and found in the town of Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk in 1181. His death, which occurred at a time of rising antisemitism, was falsely blamed on local Jews. Though a hagiography of Robert was written, no copies are known, so the story of his life is now unknown beyond the few fragmentary references to it that survive. His cult continued until the English Reformation.

Harold of Gloucester was a supposed child martyr who was falsely claimed by Benedictine monks to have been ritually murdered by Jews in Gloucester, England, in 1168. The claims arose in the aftermath of the circulation of the first blood libel myth following the unsolved murder of William of Norwich. A Christian cult and veneration of Harold was briefly promoted in Gloucester, but soon died out.

The Life and Miracles of St William of Norwich or Vita et Passione Sancti Willelmi Martyris Norwicensis is a Latin hagiography of William of Norwich by the Benedictine monk Thomas of Monmouth that was written in the second half of the twelfth century. It puts forth the false claim that a young boy named William, who had been found dead in a forest, was in fact ritually murdered by Jews, and was therefore eligible for sainthood.

Anglo-Jewish studies is the field of historical enquiry into the experience of Jewish people in England. The Jewish Historical Society of England has been central to work in this area, which began as a serious field from around the 1880s.