The Hobbit, or There and Back Again is a children's fantasy novel by the English author J. R. R. Tolkien. It was published in 1937 to wide critical acclaim, being nominated for the Carnegie Medal and awarded a prize from the New York Herald Tribune for best juvenile fiction. The book is recognized as a classic in children's literature and is one of the best-selling books of all time, with over 100 million copies sold.

Gandalf is a protagonist in J. R. R. Tolkien's novels The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. He is a wizard, one of the Istari order, and the leader of the Fellowship of the Ring. Tolkien took the name "Gandalf" from the Old Norse "Catalogue of Dwarves" (Dvergatal) in the Völuspá.

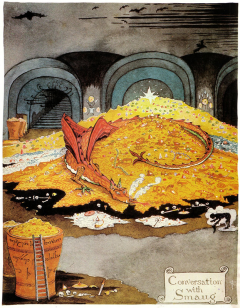

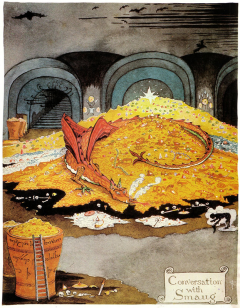

Smaug is a dragon and the main antagonist in J. R. R. Tolkien's 1937 novel The Hobbit, his treasure and the mountain he lives in being the goal of the quest. Powerful and fearsome, he invaded the Dwarf kingdom of Erebor 171 years prior to the events described in the novel. A group of thirteen dwarves mounted a quest to take the kingdom back, aided by the wizard Gandalf and the hobbit Bilbo Baggins. In The Hobbit, Thorin describes Smaug as "a most specially greedy, strong and wicked worm".

Thorin Oakenshield is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's 1937 novel The Hobbit. Thorin is the leader of the Company of Dwarves who aim to reclaim the Lonely Mountain from Smaug the dragon. He is the son of Thráin II, grandson of Thrór, and becomes King of Durin's Folk during their exile from Erebor. Thorin's background is further elaborated in Appendix A of Tolkien's 1955 novel The Return of the King, and in Unfinished Tales.

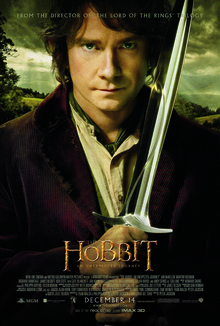

Bilbo Baggins is the title character and protagonist of J. R. R. Tolkien's 1937 novel The Hobbit, a supporting character in The Lord of the Rings, and the fictional narrator of many of Tolkien's Middle-earth writings. The Hobbit is selected by the wizard Gandalf to help Thorin and his party of Dwarves to reclaim their ancestral home and treasure, which has been seized by the dragon Smaug. Bilbo sets out in The Hobbit timid and comfort-loving, and through his adventures grows to become a useful and resourceful member of the quest.

In the fantasy of J. R. R. Tolkien, the Dwarves are a race inhabiting Middle-earth, the central continent of Arda in an imagined mythological past. They are based on the dwarfs of Germanic myths who were small humanoids that lived in mountains, practising mining, metallurgy, blacksmithing and jewellery. Tolkien described them as tough, warlike, and lovers of stone and craftsmanship.

Thranduil is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth legendarium. He first appears as a supporting character in The Hobbit, where he is simply known as the Elvenking, the ruler of the Elves who lived in the woodland realm of Mirkwood. The character is properly named in Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, and appears briefly in The Silmarillion and Unfinished Tales.

Unfinished Tales of Númenor and Middle-earth is a collection of stories and essays by J. R. R. Tolkien that were never completed during his lifetime, but were edited by his son Christopher Tolkien and published in 1980. Many of the tales within are retold in The Silmarillion, albeit in modified forms; the work also contains a summary of the events of The Lord of the Rings told from a less personal perspective.

The Hobbit is a 1977 American animated musical television special created by Rankin/Bass and animated by Topcraft. The film is an adaptation of the 1937 book of the same name by J. R. R. Tolkien; it was first broadcast on NBC in the United States on Sunday, November 27, 1977. The teleplay won a Peabody Award; the film received a Christopher Award.

Balin is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's world of Middle-earth. A Dwarf, he is an important supporting character in The Hobbit, and is mentioned in The Fellowship of the Ring. As the Fellowship travel through the underground realm of Moria, they find Balin's tomb and the Dwarves' book of records, which tells how Balin founded a colony there, becoming Lord of Moria, and that the colony was overrun by orcs.

The fictional races and peoples that appear in J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy world of Middle-earth include the seven listed in Appendix F of The Lord of the Rings: Elves, Men, Dwarves, Hobbits, Ents, Orcs and Trolls, as well as spirits such as the Valar and Maiar. Other beings of Middle-earth are of unclear nature such as Tom Bombadil and his wife Goldberry.

Gimli is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth, appearing in The Lord of the Rings. A dwarf warrior, he is the son of Glóin, a member of Thorin's company in Tolkien's earlier book The Hobbit. He represents the race of Dwarves as a member of the Fellowship of the Ring. As such, he is one of the primary characters in the story. In the course of the adventure, Gimli aids the Ring-bearer Frodo Baggins, participates in the War of the Ring, and becomes close friends with Legolas, overcoming an ancient enmity of Dwarves and Elves.

In the fictional world of J. R. R. Tolkien, Moria, also named Khazad-dûm, is an ancient subterranean complex in Middle-earth, comprising a vast labyrinthine network of tunnels, chambers, mines and halls under the Misty Mountains, with doors on both the western and the eastern sides of the mountain range. Moria is introduced in Tolkien's novel The Hobbit, and is a major scene of action in The Lord of the Rings.

The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug is a 2013 epic high fantasy adventure film directed by Peter Jackson from a screenplay by Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens, Jackson, and Guillermo del Toro, based on the 1937 novel The Hobbit by J. R. R. Tolkien. The sequel to 2012's The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, it is the second instalment in The Hobbit trilogy, acting as a prequel to Jackson's The Lord of the Rings trilogy.

The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey is a 2012 epic high fantasy adventure film directed by Peter Jackson from a screenplay by Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens, Jackson, and Guillermo del Toro, based on the 1937 novel The Hobbit by J. R. R. Tolkien. It is the first installment in The Hobbit trilogy, acting as a prequel to Jackson's The Lord of the Rings trilogy.

The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies is a 2014 epic high fantasy adventure film directed by Peter Jackson from a screenplay by Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens, Jackson, and Guillermo del Toro, based on the 1937 novel The Hobbit by J. R. R. Tolkien. The sequel to 2013's The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug, it is the final installment in The Hobbit trilogy, acting as a prequel to Jackson's The Lord of the Rings trilogy.

Scholars, including psychoanalysts, have commented that J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth stories about both Bilbo Baggins, protagonist of The Hobbit, and Frodo Baggins, protagonist of The Lord of the Rings, constitute psychological journeys. Bilbo returns from his journey to help recover the Dwarves' treasure from Smaug the dragon's lair in the Lonely Mountain changed, but wiser and more experienced. Frodo returns from his journey to destroy the One Ring in the fires of Mount Doom scarred by multiple weapons, and is unable to settle back into the normal life of his home, the Shire.

The economy of Middle-earth is J. R. R. Tolkien's treatment of economics in his fantasy world of Middle-earth. Scholars such as Steven Kelly have commented on the clash of economic patterns embodied in Tolkien's writings, giving as instances the broadly 19th century agrarian but capitalistic economy of the Shire, set against the older world of feudal Gondor. Others have remarked on the culture of gifting and exchange, which reflects that of early Germanic cultures as described in works like Beowulf. A different clash of cultures is addressed by Patrick Curry, who contrasts the pre-modern world of the free peoples of Middle-earth with the industrialising and in his view "soulless" economies of the wizard Saruman and the dark lord Sauron, based on machinery, fire, and labour.